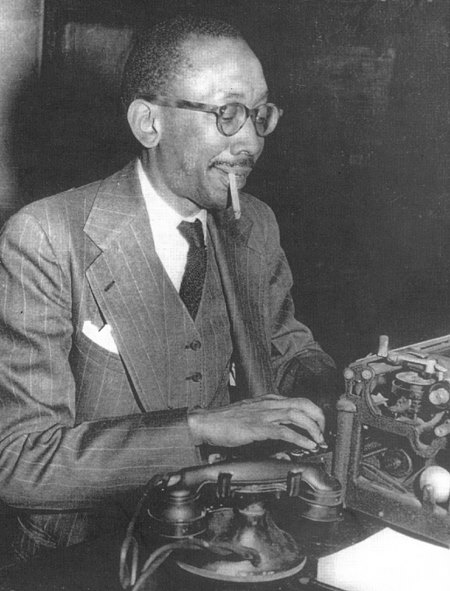

Hopkinsville, Kentucky native Ted Poston is commonly referred to as the Dean of Black Journalists. Poston will be celebrated in “Our Town Hoptown: African American Voices” as part of Hopkinsville’s annual Big Read. Founder and editor of the Hoptown Chronicle, Jennifer Brown, visits Sounds Good to discuss the program and the man behind it.

“I think what really is [Ted Poston’s] distinction is he was the first African American journalist to make a career at a white mainstream newspaper. During the ’30s and ’40s when he started his career, he was often the only black author-journalist speaking to a white audience about civil rights issues,” Brown explains. “Ted became part of the Harlem Renaissance in the late ’20s and in the ’30s…he was on the staff at The New York Post from the mid-’30s until he retired in 1972.”

“Like a lot of people in Hopkinsville, especially white residents of Hopkinsville, I didn’t know about Ted Poston until several years after he had died. I learned about him because of a woman named Kathleen Hauke, who was a scholar and college professor who became his biographer,” Brown says. “Everything I know about Ted Poston is because of Kathleen Hauke, she really did the work…I would encourage anybody to get [Hauke’s] biography on Ted…the title is Pioneer American Journalist. She also learned about Ted a few years after he died.”

“Ted was born in Hopkinsville in 1906. He graduated from Attucks High School in 1924, and then from what’s now Tennessee State University in 1928, and he pretty quickly made his way to New York,” Brown continues. “When he graduated from Attucks, his mom had died at that point. His family was kind of scattering. He was the youngest of several children in his family. That summer after he graduated, he made his own preparations to go to Nashville and go to college, but he had no way to get there other than to hitchhike, and he did. He showed up at the Tennessee Ag and Industrial School, which is now Tennessee State, and just announced, ‘I’m here!’ He had not applied, no preparation, and the college, to its credit, enrolled him and found a job for him so he could support himself. He finished in four years and got a bachelor’s degree in journalism.”

“Kathleen learned about some short stories that Ted wrote that were fictionalized accounts, and I’ll say barely fictionalized accounts, of his childhood in the 1910s in segregated Hopkinsville. They are a very upbeat, positive reveal of his life at that time,” Brown says. “When Kathleen discovered that Ted’s great friend, Henry Lee Moon – who had been the executor of his estate – had the short stories, she went to see him. He opened up a desk drawer and tossed these short stories out to Kathleen and said, ‘if you wanna try to get them published, here you go.’ That led to Kathleen’s biggest contribution to Hopkinsville, I think. She moved here around 1984…she actually rented a room from one of Ted’s childhood buddies and did a lot of research on all of these stories, which are compiled in a book called The Dark Side of Hopkinsville. It is really a great historical source for people because as good as Ted’s stories are, I’m equally impressed with Kathleen’s footnotes about who all of these characters were and how they fit into the town.”

“[In these short stories, Ted] and his buddies were around ten years old, [and they] were the heroes of all the stories. They were often outwitting the white community, but also their black elders,” Brown explains. Some titles include “The Werewolf of Woolworth’s,” “Papa Was a Democrat,” “High on the Hog,” and “The Birth of a Notion.” “[“Birth of a Notion”] was Ted’s interpretation of what happened when the very racist film, Birth of a Nation, came to Hopkinsville. Ted and his friends become the heroes of the story when they get into the projection booth at one of the local theaters and manage to play the film backward. There’s one scene where a black man is supposed to be chasing a white maiden, which feeds into the stereotype of African Americans as sexual predators. But in Ted’s story, they turned the film backward, so there’s a rescue that happens of the white maiden. Instead of being chased off a cliff, the black hero in the story is pulling her off the cliff so she doesn’t fall.”

Poston died in 1974, two years after retiring from The New York Post. Hauke first published the compilation of short stories in 1991, followed by a biography, and then a book on Poston’s journalism career. Upon hearing that a headstone was never purchased for Poston’s final resting place in Hopkinsville, Hauke also took it upon herself to buy one. “It’s very simple and graceful,” Brown says. “It just says ‘Ted Poston – Journalist’ and his date of birth and death. When Kathleen first told me about this, I wanted to write about it, and she really did not want me to…she didn’t want people to think that she was trying to get credit for something. And so around 2003 or so, Kathleen died, and in talking to her husband…he gave me permission to tell that story. So if anybody goes to Cave Springs Cemetery today, they can find Ted’s grave thanks to Kathleen Hauke.”

Poston’s influence within the world of journalism and short stories will be celebrated on Tuesday, October 22nd at 5:30 p.m. at the Hopkinsville Community College Auditorium. “This is one of the Big Read events. The Big Read in Hopkinsville this year is focused on Our Town, Thornton Wilder’s play. So this is one of many events that are being put on to explore Hopkinsville,” Brown says. “I’m going to speak at the beginning and give a little overview of Ted’s life, and then we have some local residents who are going to read from Ted’s short stories.”

For more information on “Our Town Hoptown: African American Voices” and other Big Read events, visit the Hopkinsville website or Facebook page.