Among my greatest childhood obsessions was Polly Pocket. If you were around in the ’90s, you may remember these toys solely for their sheer impracticality. They were adorable little dollhouses that came stocked with an itty-bitty plastic doll and her miniscule, fuzz-covered pets. The entire ensemble folded up neatly into a pastel compact small enough to fit in a pocket.

My favorite Polly Pocket had a cat and her kitten — until the kitten tragically disappeared in our car during a rainstorm. Looking back, the entire episode seems inevitable.

Despite my failures, Polly Pocket was my earliest instructor in appreciating small things, an ability that it turns out is invaluable in studying old buildings. Often the only traces of history left are tidbits small enough to have escaped notice.

Today’s article is a celebration of tiny things. We’ll excavate layers of paint at the microscopic level to find historical clues.

Paint analysis

I first was introduced to paint analysis in graduate school. It immediately became the favorite tool in my preservation toolbox and still is. People often treat paint analysis like some mysterious and magical, yet highly scientific, voodoo. In reality, it uses common materials, common sense, and a tiny bit of science to uncover history that lurks just beyond our eyesight.

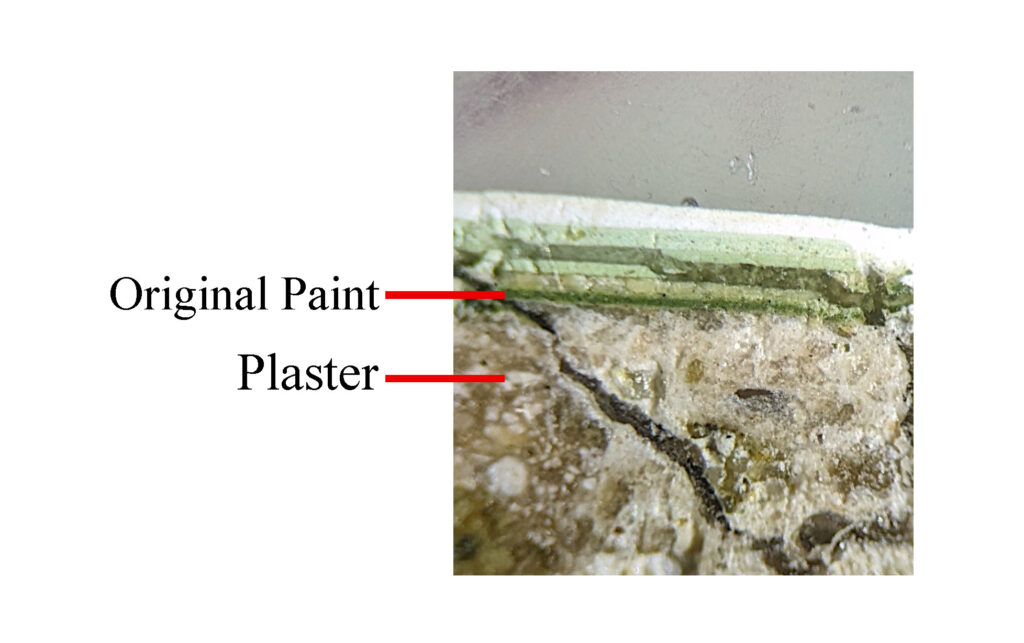

First, a sample of paint is cut with a scalpel from an architectural finish. All of the paint layers, down to the wood or plaster beneath, need to be present. This sample is set in casting resin. A cross section is cut, polished and examined under magnification. This will reveal the array of paint layers on a surface, in the order they were applied. This lineup of paint layers is called a stratigraphy, a term borrowed from archaeology. I like to think of the whole process of paint analysis as a miniscule archaeological dig.

The most complicated part of paint analysis is the interpretation, which happens in the analyst’s head. The wealth of information that lies beneath the top layer of paint may surprise you. Not only can you discover past paint colors on walls and woodwork, but paint analysis also comes in handy in dating additions, identifying disasters like fires, and determining periods of neglect in a building’s history. Paint colors age, but a cross section can reveal the original color, since the paint beneath the surface has been sealed off from oxygen, sunlight and weathering. All from a sliver of paint!

Special analysis to identify pigments and binders can be done in a laboratory, but the information most homeowners are seeking is attainable using basic materials and a little interpretation.

The smallest archaeological dig in Hopkinsville

Initially, I didn’t think paint analysis would be very useful at the Dalton house. The woodwork still has its original shellacked finish, and most of the walls were originally papered, not painted.

The most worn spot is in front of the bathroom. This was probably the only bathroom in the house in 1907. Early Sanborn maps of the property don’t show an outhouse on the grounds. So the entire Dalton household likely used this one facility. This could range from six to nine people — serious traffic for a single bathroom! The bathroom’s mode of access through the back hall suggests the Daltons didn’t really intend for most of their visitors to use it.

Oh, how wrong I was! Paint analysis has given us valuable information about how a particular region of the house was originally used.

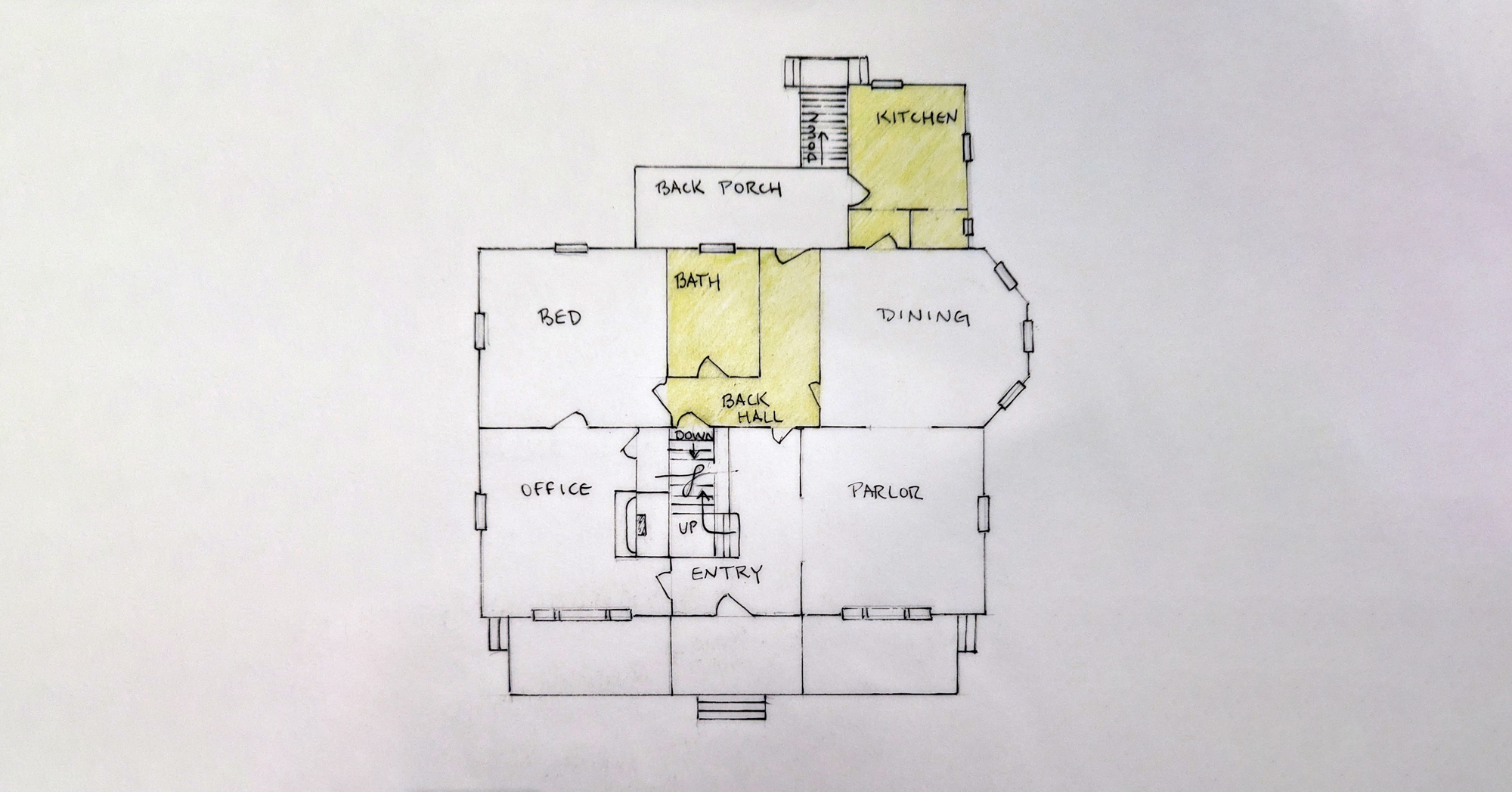

When the Daltons lived here, the house was divided into three distinct areas: public, private and service. I touched on this idea in an earlier article about the kitchen. The walls of both the public (entertainment) rooms and the private (family) realm were originally papered — the popular wall treatment in 1907. The service areas, however, were painted with a high-gloss finish for economy and cleanliness.

The late 19th century saw the discovery of germs and a revolution in hygiene. Hard, glossy paint was believed to repel germs and was easy to wipe down and keep clean. In the Dalton house, the kitchen, back hall, and first floor bathroom were all painted the same shiny, acid green. These three rooms made up the service area.

Back to the kitchen

We’ve talked about the kitchen quite a bit, but we’re going to revisit it briefly before moving to a new area.

In the last round of paint analysis, I sampled the beadboard wall separating the kitchen from the pantry and butler’s pantry, as well as the pantry shelves. The results confirmed two things I had long suspected.

- The pantry and butler’s pantry were a later modification. The first layers of paint on these elements correspond to the third finish on the kitchen walls. The pantry and butler’s pantry were probably added by the Methodist church in the early 1920s.

- The kitchen experienced a fire in recent years. The kitchen side of the beadboard wall had a heavy layer of char beneath just one layer of white latex paint.

The back hall

I’ve known for awhile that the kitchen and first floor bathroom shared the same original painted finish. But I assumed the back hall had been wallpapered, so it escaped sampling. I just recently sampled the back hall walls and found the same green paint here. This was the missing piece that clicked into motion for me the daily dance of life, circa 1907, at the Dalton house.

The back hall is not an impressive space — at first glance. An L-shaped room of about 75 square feet, it’s dark and close, with narrow corridors and a high ceiling. Surrounded and dwarfed by the house’s plethora of large, bright rooms, it’s easy to overlook. But a second glance reveals how vital this humble space is to the house’s functioning. It’s the circulatory system.

Despite its small square footage, the back hall has the most doors (six) and touches the most rooms (five, plus the back porch) of any space in the house. It connects with the entry hall and the dining room, two spaces for entertaining visitors. It also opens into a downstairs bedroom and the back porch and provides the sole access to the house’s original bathroom and basement stairs.

Backstage at the Dalton house

The Daltons probably kept the doors between the back hall and public spaces closed most of the time. But the channel between the front and back doors was vital for air circulation. Monroe Dalton took this into account when he built the house, inserting a transom over the door separating the two halls. Cracking the transom allowed airflow, but not a vista. Another transom over the doorway between the back hall and dining room circulated air through that space.

Most of the floors in the house show very little wear. This is not true in two areas: the kitchen and back hall. Just like in the kitchen, the specific locations of the wear in the back hall tell a story.

The continuation of the same finish throughout the first-floor service areas suggests to me that the cooks and maids also used the bathroom. By 1907, Jim Crow legalized segregated bathrooms in public buildings in Kentucky. All of the staff I’ve identified who worked for the Daltons were Black women. The lack of any evidence for another toilet on the property implies the had access to the first floor bathroom. In fact, the service area’s floorplan easily allowed the cook to leave the kitchen, cut across the back porch, enter the back hall, and access the bathroom without anyone in the public or private areas of the house ever seeing her.

The world below

The second area of heavy wear in the back hall is just in front of the door to the basement stairs. The work world extended into the basement. Well-lit with rough, whitewashed limestone walls and a concrete floor, this space was clearly intended to be used.

A floor drain suggestive of an early laundry indicates that this household chore was done in the basement. The Daltons sometimes employed a maid. I know of two, Mary Sugg and America Henry. Laundry would likely have been their responsibility. When I step into the worn spot by the door to the basement stairs, I always imagine them with a basket of laundry, heading down or up the stairs.

Snapshots in time

The back hall worked like backstage for the Dalton house. I find this scenario really compelling because it identifies with such a short, specific time in this house’s history. After the Daltons, I haven’t found another homeowner who had domestic staff. The kind of formal entertaining the Daltons practiced was also a phenomenon of a specific time and social class. When they packed up and left in 1924, the original function of the service area became a thing of the past.

The coming of the Methodist Church to 713 E. 7th St. was the start of a new age for the Dalton house. In June 1924 — 100 years ago next month — Monroe Dalton sold the house to First Methodist Church and moved to a little brick bungalow on North Main Street.

Grace Abernethy is a historic preservationist and artist who specializes in caring for and recreating historic architectural finishes. She earned her Master of Science in Historic Preservation from Clemson University in 2011 and has worked on historic buildings throughout the eastern United States. Abernethy was a recipient of the South Carolina Palmetto Trust for Historic Preservation Award in 2014 and won 2nd place in the Charles E. Peterson Prize for the Historic American Buildings Survey in 2011. She and her husband, Brendan, moved to Hopkinsville from Nashville in 2020. She works as an independent contractor and is a board member of the Hopkinsville History Foundation.