“Hopkinsville has had its first experience with an automobile this week,” The Kentuckian newspaper reported on Sept. 26, 1902. The editor glibly noted this as “a good thing for editors and other rich people.”

The owner of the car was from Louisville, and the spectacle sparked an urgency among residents of Hopkinsville and Christian County to purchase their own automobiles.

The garage

Someone recently asked me what the most surprising thing was that we had found in the Dalton House. I must be desensitized from spending so much time poking around old buildings. All that came to mind in the moment were an enormous rat skeleton curled up on a shelf in the basement and a stash of old cigarettes tucked under our bedroom baseboard. Not quite it!

And then I had an epiphany. Hidden in plain sight all along, it had amazed me the first time we visited the Dalton House. It’s such a large thing. In fact, it’s an entire room.

It’s the garage. Lots of houses have garages — but not houses built in 1907. Many houses in Hopkinsville built around this time didn’t even have a bathroom, much less a garage! And the Daltons’ garage was defintely purpose-built.

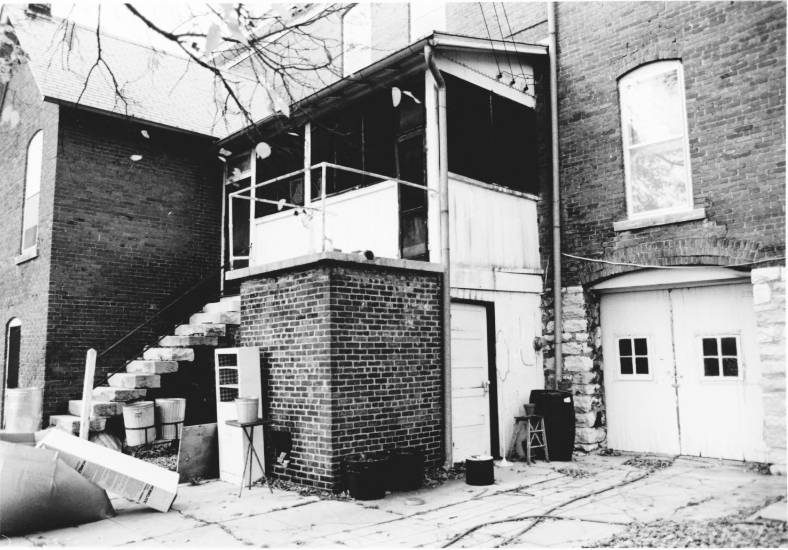

The garage took me completely by surprise when we first visited the house. It’s a cavernous space in the basement with whitewashed rock walls and no windows, about 30 feet deep by 15 feet wide. It’s accessed by a garage door at the back of the house as well as a door into the main hall of the basement. There was no power in the house at the time, so Brendan, our real estate agent Dustin and I nosed around the room with our phone flashlights for awhile before realizing that we were standing in a garage. How modern!

The story of how the Dalton House came to be built with a garage dives into Hopkinsville’s transportation history and involves yet another Dalton sibling in a surprisingly relevent way.

Autos, horses and streetcars

I knew little about Hopkinsville’s transportation history before I began researching for this article. It’s fascinating. Did you know Hopkinsville nearly had a streetcar?

By 1906, only a few Hopkinsville residents had bought into the new automobile craze. Most still drove horse-drawn buggies. The Kentuckian noted on Jan. 18 of that year that cars had disappeared from the streets and horses were once again able to go about the city without being frightened. Automobiles were still far too novel and expensive for most people.

- RELATED: Parking meters illustrate changing times in downtown Hopkinsville

- RELATED: Auto dealer’s 1922 display tells a colorful story

In fact, a more palatable and accessible new form of transportation was expected on Hopkinsville’s streets: an electric streetcar. The city announced a franchise ordinance for a streetcar just nine days before the article about the horses ran. Compared to the $700 needed to buy an automobile, streetcar fare for any distance in the city was capped at 5 cents. There would be a passenger line as well as a freight line, and the electrical power plant needed to operate the streetcars would also provide electricity for lighting throughout the city. It was the beginning of a new, electric age!

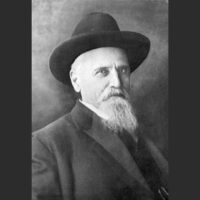

Who was behind all of these plans? I’m sure you’ve guessed by now that it was a Dalton. Hilliard Dalton, the third Dalton brother, proposed and purchased the franchise.

Hilliard M. Dalton

Born in 1873, Hilliard Dalton was popular, progressive, energetic, and had a robust entepeneurial streak, perhaps even stronger than his two older brothers. Hilliard was involved in the Dalton Bros. Brick Co., but he also had a number of successful side ventures with ties to rail transportation.

The first of these was the Dalton Stone Co., which Hilliard Dalton founded around 1899, when he was just 26 years old. Dalton Stone dealt in crushed stone, which was used in constructing railways. When the company incorporated in 1902, The Kentuckian reported that thousands of miles of rail had been laid on Dalton crushed stone, and thousands of workers in Hopkinsville had been employed by the company.

Next, Hilliard Dalton jointly founded Dalton & Marsh Contracting with Frank Marsh of Evansville, Indiana. This was headquartered in Hopkinsville but operated out of Lexington, South Carolina. It ran a crusher plant at a quarry, again supplying stone for the railroad.

Hilliard Dalton’s third endeavor was the Belt Line Railway Co. This railroad would lay track to connect all the different railroads coming into Hopkinsville. The Louisville and Nashville, Illinois Central and the Tennessee Central railways all passed through the city, but not all of their tracks connected. The L&N depot still stands on East Ninth Street, but the IC depot is long gone. It used to stand by the Little River, near where the public library is today. The Belt Line Railway Co. incorporated in 1905, with Hilliard Dalton as president.

And there was the streetcar venture. In January 1906, Hilliard Dalton proposed the streetcar franchise to the city, which passed the ordinance the following month. He promptly bought the franchise. He planned to begin constructing the infrastructure on May 19, 1906, with rails being laid by February 1907.

An unforseen accident changed everything.

Death of a dream

Hilliard Dalton stopped at the Elks Club on the afternoon of May 6, 1906. He was recovering from an illness of several weeks and had a headache. Taking a pain killer, he went upstairs and lay down on a couch. The manager, Henry Blumensteil, was the only other person in the room. He went about his work while Dalton tried to nap.

After tossing and turning for a half hour, Hilliard Dalton went to remove a small pistol from his pocket. He either mishandled or dropped the gun. It fired, sending a bullet through his stomach. Blumensteil raced downstairs and fetched two witnesses, and Hilliard Dalton gave a statement exonerating him. He died the next morning, just 33 years old.

Hilliard Dalton’s death shocked Hopkinsville. He left a young wife, Cora, and 9-year-old son, Wesley. Alongside Hilliard Dalton died Hopkinsville’s electric streetcar.

Missed connections

Had his life not been abruptly cut short, Hilliard Dalton may have been the star of the Dalton family. Hopkinsville would have had an electric streetcar, which could have delayed the ascent of the automobile in the city for a few years, and his brother Monroe Dalton’s 1907 house may not have been built with a garage.

In the void left by the aborted streetcar venture, the automobile took its place as the future of personal transportation in Hopkinsville. Monroe Dalton purchased the lot at 713 E. Seventh St., just seven months after Hilliard’s death and made plans to construct a house — with a built-in garage. This was planning for the inevitable future.

But the automobile still proved slow to catch on in Hopkinsville. In 1910, Charles Meacham published a list of car owners in the county. There were just 29, and Monroe Dalton was not among them. While he didn’t have a car in his garage, Monroe Dalton had the foresight to realize that one day someone would probably want to park one there.

The age of the auto

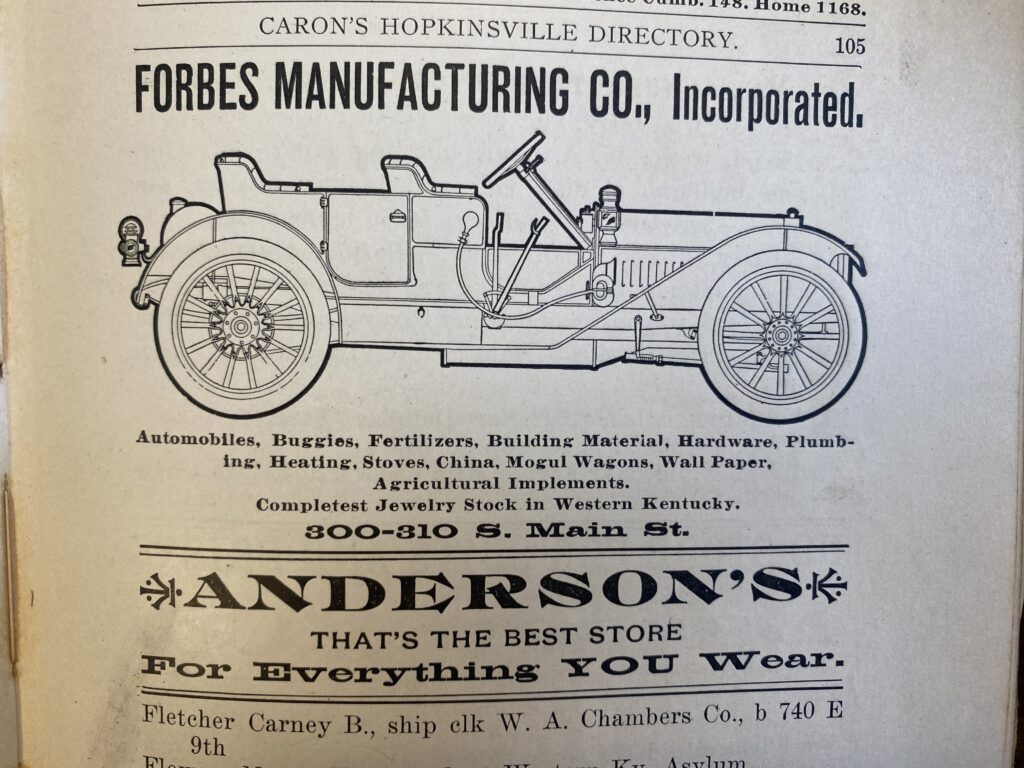

Just two years later, 29 automobiles had grown to 117. Forbes Manufacuring listed an advertisement for their cars in the 1910-1912 Hopkinsville city directory. And in 1914, Dalton’s brother-in-law and nephew, Lucien and Latham Davis, incorporated a car dealership, Service Auto Livery Co., with Frank Bassett.

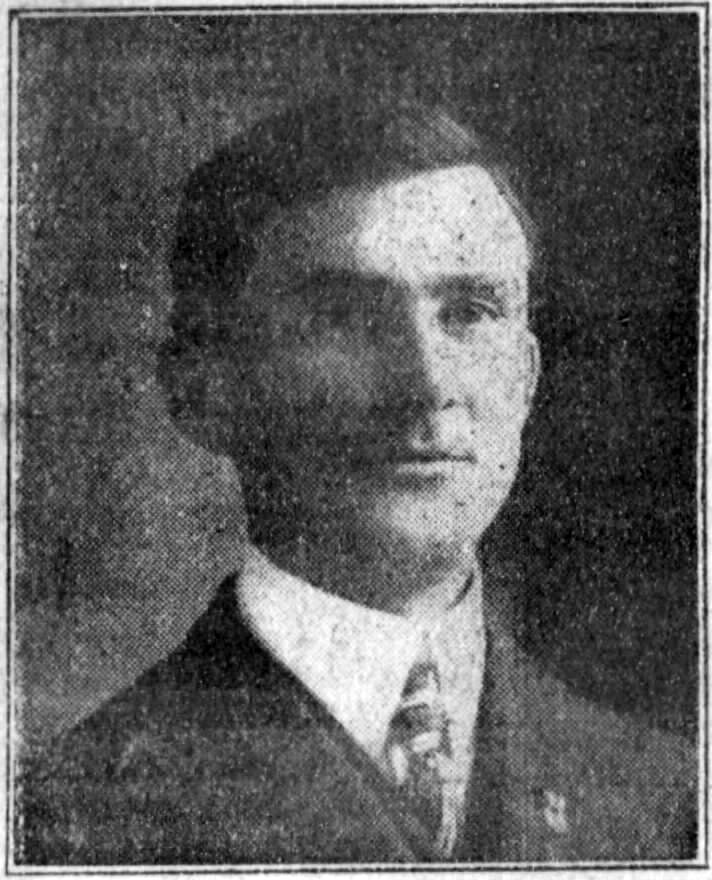

It turns out Hilliard Dalton’s son, Wesley, also had a fascination with transportation. By the time Wesley’s generation reached maturity, the automobile ruled Hopkinsville’s roads. In 1915, 19-year-old Wesley Dalton made a name for himself by racing a Harley Davidson motorcycle at the Pennyroyal fair. He and his cousin Latham Davis went on to open the Dalton-Davis Motor Company in 1919.

The 1983 National Register pictures for the Monroe Dalton House show the garage with its charming original double-doors. They are of board and batten construction, just like the basement door. In the years between 1983 and now, someone removed the double doors and replaced them with an automatic, aluminum garage door for more convenient use. It’s an unfortunate but solid affirmation of Monroe Dalton’s prescience that future owners would want a place in the house for their automobile.