Rylee Dakota Monn’s salary as a day care teacher mostly went to pay for child care for her own two sons. Rylee Dakota Monn with sons, Walker, left, and Levi. (Personal photo)

“I was working full time but I wasn’t making any money for myself or making much of a contribution to the household,” said Monn, who works at Baptist Health Child Development Center in Lexington. “It was just enough to maybe help pay a utility bill. The way it was, I’m not sure it was even worth working.”

Now, her child care costs are paid through the innovative Child Care Assistance Program Income Exclusion, financed by federal funds that end next year. Under the year-old program, the state pays day care centers the $6,600 average cost for a child for 3,200 families with 5,700 children.

However, most federal funds that bolstered families and day care centers during the pandemic ended Sept. 30. Efforts to approve more congressional funding are not promising. So, the states must find the money and the ideas to deal with a long-neglected system.

In response, the Beshear administration has committed an extra $50 million to help centers before the General Assembly meets in January. Using federal funds that ended in September, the state plans to continue policies that allow more families to afford care. And the legislature last year approved a program that matches subsidies employers give their workers.

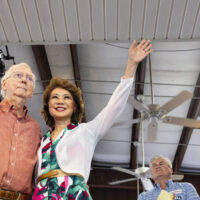

All of this is encouraging. But what’s urgently needed is a comprehensive budget plan to counter the real prospect of the state’s too-few centers closing, laying off an already anemic workforce, raising fees, and reducing already-low wages. Sarah Vanover

At least 32 states have expressed interest in following Kentucky’s lead in helping child care workers. The idea was a response to a dramatic drop in the number of children in centers, said Sarah Vanover, a leader in the program’s creation who is now policy and research director for Kentucky Youth Advocates. State officials realized that parents could not find slots. The classrooms were there; the workers were not. The average $12.39 hourly pay for child care workers could not even compete with fast-food jobs.

- RELATED: School system, industries partner to open child care facility in 2023

- RELATED: More help for undergrads’ basic, child care needs could up Kentuckians’ earning power

“Ninety-eight percent of jobs pay more than child care workers, including dog walkers,” said Vanover. “So, they can work with kids in a labor-intensive job or stock shelves and make $5 an hour more.”

Monn can now afford community college classes to train for a job in the medical field. Having her sons, ages 4 and 2, at the same place where she works is also a benefit. “I was taking care of people’s kids everyday but couldn’t afford to have the same treatment for my own.” Beth Morton

Beth Morton, director of the center where Monn works, currently has six workers with eight children through this program. It’s proven to be a good marketing tool for her 32-person staff, she said.

“It’s not that child care workers are more important than other workers. But every other workforce is dependent on child care,” said Morton, a member of a gubernatorial advisory board on early childhood development. “I am very concerned that we are going to see a drop in child care slots. The only thing a center can do when it loses that funding is to lower quality and increase costs.”

A majority of Kentucky voters, regardless of political party, support using taxpayer money to provide high-quality child care, according to a June survey by the Prichard Committee for Academic Excellence and The United Way of Greater Cincinnati.

Prichard proposes a $1 billion annual investment by 2026 for a comprehensive system of child care and pre-school assistance, all-day kindergarten, teacher training and school transportation. Charles Aull

An estimated 45,000 Kentuckians struggle due to a lack of child care and early-education access and affordability, according to a 2022 Kentucky Chamber of Commerce report. More than 46% of parents in a 2020 survey said someone in the family had quit a job, did not take a job, or changed jobs due to child care issues.

“We are encouraging lawmakers to take the child care issue very seriously,” said Charles Aull, executive director of the chamber’s Center for Policy and Research. “We are very vocal about how child care intersects with our economic challenges. The question is: What is the best strategy for it?”

Another unique program, the Employee Child Care Assistance Partnership, matches child care subsidies that businesses and nonprofits provide workers. There is no income limit for participants. Funded with $15 million in state money, the one-year pilot program has so far signed up 27 employers paying subsidies to 82 workers for 113 children.

“It’s slow going. But considering that we stood this up in a year, I feel good about it,” Andrea Day, director of the Kentucky Division of Child Care, told the Interim Joint Committee on Appropriations and Revenue last month. “This is a really good investment in child care in Kentucky.” Andrea Day

While Florida, Wisconsin and Michigan have similar programs, Kentucky’s is the only statewide, taxpayer-funded one, Day said. She generally agreed with impressions from advocates that the program needs better marketing, and businesses need guidance about updating personnel policies and navigating state bureaucracy.

While the program will be carried over to the next year, it really needs to be funded for several years to get it off the ground.

“What it needs is more time and certainty,” said Aull of the chamber. “Employers want to see how a program evolves before jumping into it.”

Meanwhile, Kentucky’s pre-school children continue to lose ground. The state ranks No. 41 in the nation in the number of 3- and 4-year olds enrolled in pre-school, resulting in 53 percent of kindergarteners identified as not ready for the classroom.

One advocate described Kentucky’s child care system as a sickly patient temporarily stabilized by an infusion of federal funding. That treatment has ended. What now?

“Before Covid, people didn’t realize the importance of child care,” said Morton, the day care center director. “We now know we need to do something. But there is no plan.”

This article is republished under a Creative Commons license from Kentucky Lantern, which is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Kentucky Lantern maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Jamie Lucke for questions: info@kentuckylantern.com. Follow Kentucky Lantern on Facebook and Twitter.