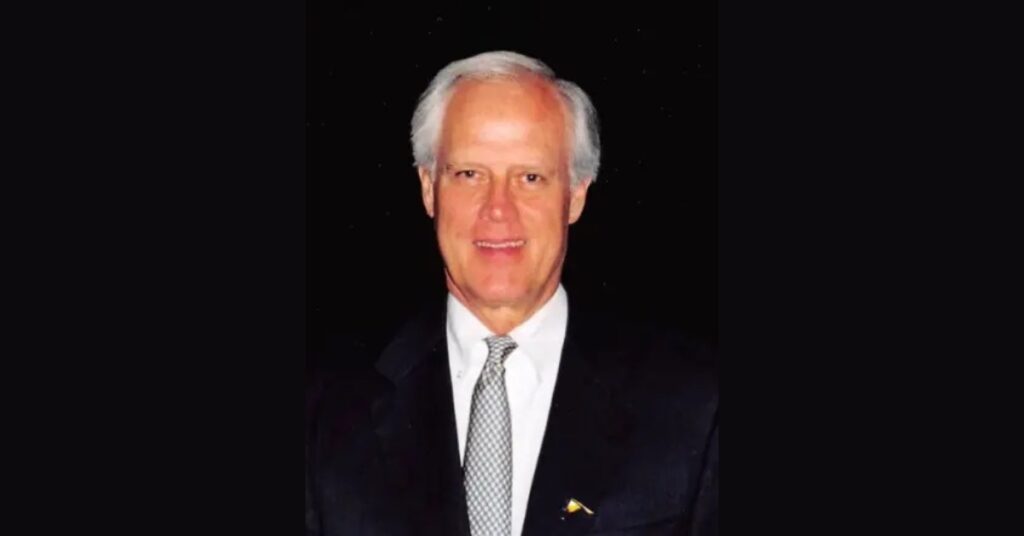

George L. Atkins Jr., who died Sunday night at 82, was a politician for barely a decade. But he was a touchstone for modern Kentucky politics and historical currents that go back more than a century: the corrupting force of big business, voters’ desire for reform, the influence of the news media and the compromises made by people in public life.

Atkins’ political life began at the University of Kentucky, where he played basketball for Adolph Rupp, and in his hometown of Hopkinsville, where he was appointed and elected mayor in his early 30s. His smooth but forthright manner was so appealing that he was easily elected state auditor in 1975, and even before he took office was on short lists of Democratic prospective candidates for governor in 1979.

Atkins used the authority of the auditor’s office in a way that none of his predecessors had, exposing shady deals in the administration of Democratic Gov. Julian Carroll, and that was the basis of his campaign. There was another major reform-oriented candidate, former Louisville Mayor Harvey Sloane, and Democratic sage Ed Prichard and others thought they should team up, perhaps with Atkins running for lieutenant governor. Sloane told me that a Louisville meeting was arranged, but a snowstorm kept Atkins from getting there. Then businessman John Y. Brown Jr. jumped into the race shortly before the filing deadline, and the meeting wasn’t rescheduled.

In such a fractured race, newspaper endorsements took on more importance, perceived or real. Keith Runyon, who was on the editorial board of The Courier-Journal and The Louisville Times, told me Publisher Barry Bingham Jr. was preparing to endorse Atkins until his father, company Chaiman Barry Bingham Sr., steered the endorsement to Sloane, to whom the elder Binghams were close. (That set the stage for the newspapers’ endorsement of Republican George Clark for mayor over Sloane in 1981, which contributed to the family dissension that led to the papers’ sale in 1986.)

Without a big endorsement and polling poorly, Atkins withdrew and backed Brown, who had suggested privately during a KET debate days earlier that they “get together.” Atkins told me then that “the real key” was a classic column by The C-J’s John Filiatreau that portrayed the Democratic field as a poker game robbed by a Republican bandit as they argued. Atkins’ endorsement helped nominate Brown, who finished 4.49 percent ahead of Sloane.

Atkins became Brown’s finance secretary and cabinet secretary, a sort of deputy governor, but also the target of some Democrats who didn’t care for Brown. At the 1980 Fancy Farm Picnic, former Gov. A.B. “Happy” Chandler said the state wouldn’t have bought its famous Sikorsky helicopter “if George Atkins were still alive.” The quip stuck so well that Brown himself used it at the next picnic in reminding the crowd that he was selling the ‘copter, which had brought him to Fancy Farm: “If George Atkins were still alive he’d never let them take that helicopter from me.” The headline in the Owensboro Messenger-Inquirer read, “Atkins roasted again at Fancy Farm.”

Chandler, who entered politics in 1927, had a knack for reflecting the public mind, in which Atkins had evolved from a crusading reformer to a high-flying governor’s instrumentality. That image lingered in 1983, when he ran for lieutenant governor. But he probably would have won if not for this: A supporter of Sloane, who was running for governor, asked, “Who do you want for your lieutenant?” Sloane replied, “Steve Beshear,” then attorney general. Sloane’s whisper into the supporter’s ear was loud enough for C-J reporter Robert T. Garrett to overhear, and his story put Sloane on the defensive a week before the primary.

After Beshear won by 4.8 percent, he told C-J reporter Richard Wilson that Sloane’s remark helped him run a strong second in Jefferson County to former County Judge Todd Hollenbach, and that was the key to his victory. Several others were running for lieutenant governor, so the remark clearly hurt Sloane, who lost to eventual Gov. Martha Layne Collins by only 4,532 votes, 0.7%. Beshear came up short in the 1987 gubernatorial primary, but was elected governor in 2007 and 2011, setting up his son Andy to likewise serve two terms.

So, many political threads ran through George Atkins, but he was spent as a politician. He had a family to support and joined Humana, then a hospital company, and became its chief lobbyist.

In 1990, Humana was determined to have the legislature relax limits on hospital expansion in Louisville. The deciding vote for the bill was cast by state Sen. Patti Weaver of Walton, after Atkins agreed to help her get a state job. When she failed the state personnel exam and threatened to tell her story, Atkins funneled $10,000 to her through Sen. Helen Garrett of Paducah, who was convicted on an unrelated charge in a broad federal investigation of state-government corruption, mainly in the legislature.

Atkins pleaded guilty to mail fraud and was sentenced to 24 weekends in jail and 400 hours of community service and fined $10,000. Humana apologized for the bribe and paid the $92,437 cost of the investigation.

In sentencing Atkins, Judge Joseph Hood was harder on Humana, suggesting that the company knowingly blinded itself to his actions as it pressed him for results. Atkins told Hood the bribe money came from a Humana account that he could use on his own. Humana said afterward that it knew of no illegal acts but “Closer supervision might well have prevented this occurrence.”

Atkins, facing the possibility of a year in prison, told Hood that he hoped “in some way this could be a wake-up call for thousands of people just like me … You can’t get so wrapped up in your job, so wrapped up in your career … that you don’t stop and ask, ‘Where does this lead, where does this go?’”

Atkins remained a health-care consultant in Washington and was largely forgotten in Kentucky, but his words are worth remembering. If anyone ever had a meteoric career, it was him: a young man full of ideals and promise who came up just a little short in his last election, and wound up cratering. There but for God’s grace go many of us. May his example be remembered.