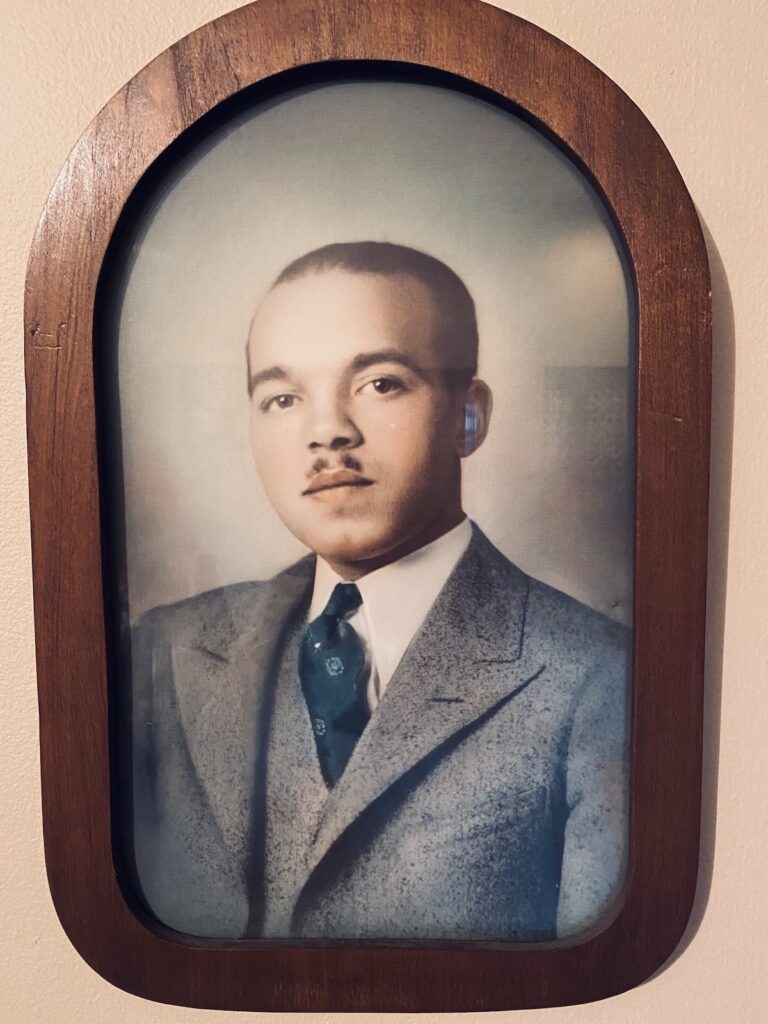

Hopkinsville native Philip Carruthers Brooks achieved an elite status in 1927 when he graduated from Howard University’s College of Medicine with 45 classmates. The only two historically Black colleges training physicians at that time were Howard in Washington, D.C., and Meharry in Nashville.

The medical degree and an internship at the state-of-the-art Freedmen’s Hospital in Washington should have set Brooks on his way. But he faced challenges.

Shortly after he left Howard, Brooks headed out to find a community where he could practice medicine. Years later, he described how he toured parts of Ohio, Michigan, Indiana and Maryland before deciding that Toledo would be his professional home.

Plans in place, he returned to Kentucky to borrow $2,000 he needed to set up the practice. But with no assets to secure a loan, he found himself seemingly stuck where he had started — Hopkinsville.

He was broke.

So Brooks, one of the town’s most highly educated citizens, took a job waiting tables at a local hotel until he finally landed a position in 1929 earning $150 a month to treat patients.

“At first, he could barely feed his wife and new baby,” a reporter for the Nashville Banner newspaper wrote in a Nov. 12, 1959, profile of Dr. Brooks. “He walked three miles to and from a staff position at Western State Hospital just outside the city, and nights he walked all over Hopkinsville making house calls.”

Brooks sat for a four-hour interview with staff writer Robert Churchwell, himself a pioneer as the first Black journalist hired for a full-time reporter’s job at the Banner in 1950. Churchwell spent five years typing “Negro beat” stories from home and handing the copy off to an editor because he was barred from entering the Banner’s all-white newsroom until about 1955.

Churchwell framed the Brooks profile as a “Made in America” success story. His interview — which occurred after Dr. Brooks was well established as the director of a 30-bed hospital that primarily treated Black patients — represents one of the most detailed, personal reports on Dr. Brooks that survives today.

Churchwell described how Dr. Brooks worked 16 hours or longer some days, dividing his time between Brooks Memorial Hospital and numerous house calls. On his busiest days, he saw at least 50 patients.

“I tell employees at the hospital to treat these patients like they would want their mothers, fathers, sisters and brothers treated, and they won’t go wrong,” Dr. Brooks said to Churchwell. “People have been very good to me … I only engineered the program.”

Early life

Philip Carruthers Brooks was born on Sept. 21, 1901, to Henry and Carrie Brooks. He was the first of 13 children.

Before graduating from Attucks High School, Brooks had already started putting back a little money for college, investing 10 cents a week in a Christmas savings club. He started working as a boy and continued through college to pay for his education. He said in the 1959 Banner interview that his father, who worked as a janitor, cook and carpenter, also helped with some of the expenses.

While he was preparing for a career in medicine, Brooks learned firsthand that Black Americans faced health challenges that could drastically alter a family. His mother died in 1922 after a stillborn birth that left her with an infection. She was 42. His father died five years later from stomach cancer. He was 53.

Dr. Brooks’ decision to practice medicine in Hopkinsville would prove to be a crucial asset for the town, which has been among Kentucky’s more racially diverse communities going back to the years before the emancipation of enslaved people. The county’s racial diversity can be traced to the region’s reliance on tobacco, a labor-intensive crop that drove Christian County’s relatively large slave population in the years leading up to the Civil War.

The community was growing rapidly as Brooks transitioned from boyhood to college and into his medical practice.

The year before Dr. Brooks was born, the population of Hopkinsville was roughly 7,300. Shortly after he returned home from medical school, it had grown to approximately 10,750. And the year after his interview with the Banner, Hopkinsville’s population had grown to 19,465.

A hospital for Black patients

Dr. Brooks had a full-time practice separate from Western State Hospital by around 1933 — and by 1940, if not earlier, he was making plans to build a hospital for Black patients, who had few options for urgent medical care in the region. Jennie Stuart Memorial Hospital was still segregated and would continue to deny treatment to Blacks until integration was forced through compliance with a federal grant in the mid-1960s.

Construction on an 18-bed hospital adjacent to the Brooks home at South Virginia and Second streets began in 1940. The project slowed two years later as construction of Camp Campbell (now Fort Campbell) affected labor costs. Brooks Memorial Hospital was completed in 1944. Later the hospital expanded and provided 30 beds.

The hospital served a large region. A notice published in the Kentucky New Era on Jan. 19, 1954, listed patients from Greenville, Cerulean, Madisonville, Crofton, Drakesboro, White Plains, Guthrie, Hopkinsville, Clarksville, Tennessee, and Thomasville, Georgia.

By the late 1950s, Brooks Memorial employed 10 nurses, an orderly, a receptionist, a cook and an office worker. Dr. Brooks was the only full-time physician on staff at his private hospital, although other Black physicians occasionally sent patients there and some white doctors might have consulted on cases.

Melton Brooks, one of the doctor’s nephews, told Hoptown Chronicle that a white doctor in Hopkinsville helped teach his grandfather surgical skills. The two doctors knew each other through the Episcopal church. Dr. Brooks was a member of the Chapel of the Good Shepherd, a Black Episcopal church on Second Street. He transferred his membership to Grace Episcopal after Good Shepherd closed and eventually became the site for the Aaron McNeil House.

A grandson, former Hopkinsville City Councilman Phillip Brooks, still remembers the layout of the hospital. The first floor had a reception area, an office, a lab, exam rooms and a kitchen. The second floor had an operating room, X-ray, six private rooms and two infirmary rooms with several beds each.

There was a switchboard on the second floor. Meals for patients were lifted from the kitchen to the second floor by a dumbwaiter.

The same person who cooked for the patients also prepared meals for Dr. Brooks and his family, including his wife, Ethel, and sons Phillip and Cowan.

“He ate the same thing that the patients had,” his grandson said.

Breadth of practice

Patients, family members and other doctors who recall Dr. Brooks’ practice still marvel at the scope of his work and the hours he put in.

“How he managed to do all of that and have a life, I have no idea,” said Hopkinsville family physician Dr. Chester Crump.

Dr. Crump never knew Dr. Brooks but he now sees many of his former patients. He’s heard stories about surgeries, late-night house calls and numerous babies delivered at Brooks Memorial.

Medicine today is highly specialized, but Brooks did not have that luxury. Many of his patients would have gone without treatment or been forced to look for a doctor many miles from Hopkinsville if Brooks had turned them away — or worse, never established his hospital.

One story in particular impresses Dr. Crump. A man now in his 70s broke his femur when he was 9 years old. Dr. Brooks operated on him and placed a metal rod in his leg to repair the damage. The leg healed and the boy eventually ran track in high school.

Dr. Brooks saw patients all hours of night, patients who couldn’t pay him and patients that other doctors wouldn’t see.

In September 1958, Jet magazine published this brief report:

“A white stock car racer lay injured for an hour while trying to get treatment from white doctors in Hopkinsville, Ky., but a Negro physician responded within 10 minutes, according to complaints filed with the Kentucky Medical Assn. Seven witnesses said that Dr. P.C. Brooks treated Clinton Reynolds, 27, for nose and lip cuts, two cracked ribs and multiple lacerations at Brooks Memorial (Negro) Hospital after at least seven white doctors refused to come to the racer’s aid at white Jennie Stuart Hospital.”

Former patients still remember how reassuring it was when Dr. Brooks arrived for an urgent house call.

“At night he’d come and almost look like he was sleep walking,” said Billie Todd, a 1959 graduate of Attucks High School who knew Dr. Brooks as a patient and an employee. Right out of high school, she went to work for the Brooks family’s loan company, Fraternal Loans.

“He didn’t turn down anyone,” Todd said.

Somehow, though, Dr. Brooks did make time for civic work and a social life.

Public service

In November 1962, he became the first Black candidate elected to Hopkinsville’s former city school board.

“In his campaign, Dr. Brooks said that Negroes, who make up 36 percent of the Hopkinsville population, were entitled to representation on the school board,” a newspaper wire service reported.

A story published on April 21, 1968, by the Louisville Courier Journal included comments from Dr. Brooks about efforts to secure city funding that would provide a full-time staff member for the Human Relations Commission. A reporter wrote:

“Dr. P.C. Brooks, Hopkinsville Board of Education member, said the commission may be called upon to help deal with racial problems in the schools.”

Brooks told the paper, “We have some teachers in our system who are a little narrow-minded. It’s a job for the Board of Education to clear up. If we fail, we may seek help from the commission.”

Enjoying life

Outside of his medical practice, Dr. Brooks had several diversions that he enjoyed. He owned a farm, which is still in the family, a few miles east of town on U.S. 68 where he had dairy cows, horses, pigs and tobacco. There was a swimming pool for the family at the farm.

He enjoyed an occasional day watching thoroughbred races and had a box seat at Churchill Downs. Joe Vance, a retired physician, remembers arriving in Louisville one day for the Kentucky Derby and seeing Dr. Brooks and a few other men, all “dressed beautifully” and climbing out of Brooks’ car, a Rolls Royce. It was his traveling car, said his grandson.

Dr. Brooks also loved a good circus. He kept inviting his grandchildren to go along with him years after they had outgrown the experience. When they asked him why he wanted to keep going to the circus, he told them it was something he couldn’t do when he was young because his family couldn’t afford it.

Although he was soft-spoken, Dr. Brooks had a clever sense of humor. On the day in 1958 when he delivered Melton Brooks, the doctor was thinking of the space race raging between the United States and the Soviet Union. So as the baby boy arrived, Dr. Brooks proclaimed, “Here comes Sputnik!” — and to this day, the nephew goes by the name of a Soviet space satellite.

Ending segregation

On Dec. 12, 1965, the Kentucky New Era ran a story about changes coming to Brooks Memorial Hospital and Jennie Stuart.

Dr. Brooks confirmed he was considering closing his hospital as he anticipated Jennie Stuart would eventually accept Black patients and allow Black physicians to practice medicine there. The story said he had “taken preliminary steps to gain admittance to the staff.”

He told the paper, “If I should receive full privileges, there would probably be no need to continue operating my hospital.”

At that time, Jennie Stuart was completing a $1.4 million expansion that doubled its capacity to 200 beds. A $700,000 construction grant through the federal Hill-Burton Act required the hospital to integrate, according to the story.

As often occurred during the integration of long-standing institutions, Brooks Memorial did not close immediately after Jennie Stuart began admitting Black patients. Brooks Memorial remained in business for another decade. During the transition, Dr. Brooks gained staff privileges at Jennie Stuart.

Brooks Memorial closed in 1977.

Five years later, Dr. Brooks was still seeing patients. On a Saturday night, Nov. 27, 1982, he went to bed early and turned on the radio to listen to a Christian County High School football game in Louisville. His grandson Phillip Brooks was playing and had one of the best games of his high school career, rushing for more than 150 yards.

The next morning, his family learned Dr. Brooks had died during the night with the radio playing at his bedside. He was 82.

This is the last story in a three-part series about Dr. Philip Carruthers Brooks and the hospital he ran from 1944 to 1977. Read the first installment by Alissa Keller, and the second part by Grace Abernethy.

Jennifer P. Brown is co-founder, publisher and editor of Hoptown Chronicle. You can reach her at editor@hoptownchronicle.org. She spent 30 years as a reporter and editor at the Kentucky New Era. She is a co-chair of the national advisory board to the Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues, governing board president for the Kentucky Historical Society, and co-founder of the Kentucky Open Government Coalition.