There’s more to Brooks Memorial Hospital than meets the eye.

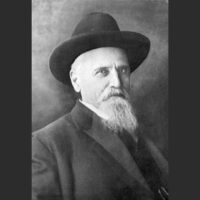

The site is a landmark in Hopkinsville. Filling the corner of South Virginia and East Second streets, the stone house and hospital command attention. Dr. Philip Carruthers Brooks, a Black physician, founded the hospital in 1944. It operated for 33 years, closing its doors in 1977. During segregation, the hospital filled a critical role not just in Hopkinsville, but regionally.

In the second part of a three-part Black History Month series about Brooks, I’m exploring the history of the building at 201 S. Virginia St. Buried beneath the stone veneer lies a story that stretches back much further than the days of Dr. Brooks.

Philip and Ethel Brooks

Today, 201 S. Virginia St. reflects changes made by the Brooks family. Dr. Brooks bought the house and lot around 1943. At that time, the house was frame, not stone, and there was no hospital.

Brooks soon began building the hospital, which he attached to the house. He clad the house in a stone veneer, built a small addition on the north side, and added Craftsman-style elements. Aesthetically, the two buildings now matched.

When Brooks Hospital opened in 1944, it served Black and white patients. Newspaper articles reveal the hospital filled not just a local, but a regional void. Patients from Central City, Bowling Green and Clarksville all appear in its rolls. Although Dr. Brooks considered closing it in 1965, when Jennie Stuart integregated, Brooks Hospital remained open until 1977.

- RELATED: Philip C. Brooks Sr. built Hopkinsville’s only hospital for Black patients during segregation

Dr. Brooks died in 1982, and the property remains in the Brooks family today.

But the house at 201 S. Virginia had already undergone substantial changes when Dr. Brooks bought it. For these, we need to look to the previous owner, Peter Postell Jr.

Peter Jr. and Fannie Postell

It seems fitting that the Brooks and Postells, two Black families of such magnitude in Hopkinsville, have owned and occupied the same house for more than the last century.

Born in 1871, Peter Postell Jr. was the son of Peter and Pauline Buckner Postell. His father was considered by contemporaries to be the wealthiest Black man in Kentucky. Postell Sr. was a shareholder in Hotel Latham, a real estate mogul, and ran a lucrative mercantile business.

Peter Jr. was partner in and heir to the mercantile business. Like his father, he invested in real estate. On the civic side, Peter Jr. was involved in Black education and served multiple terms on the city’s colored school board.

Within the Postell household, however, the true champion of education was Fannie, Peter Jr.’s wife. She was a professional educator with a stellar career. Born in 1863, Fannie Bronson graduated from Berea College in 1890 and began teaching in Hopkinsville at Jackson Street School, later known as Booker T. Washington School. She and Peter Postell Jr. married in the early 1890s and bought 201 S. Virginia in 1894.

Fannie Postell’s career exploded in the 1900s. In 1907, she was elected Superintendent of Hopkinsville’s colored schools. She was instrumental in creating Attucks High School, Hopkinsville’s segregated Black secondary school, and served as principal there from 1927 to 1936.

The backdrop for this rich period in the Postells’ lives was 201 S. Virginia St., but we would probably not recognize this house as we do today. When the Postells moved in, it likely looked similiar to when it was built. One story, frame, T-shaped, with a small front porch, it was a cottage. It was probably just two rooms wide, divided by a central hall. An ell on the back doubled the square footage.

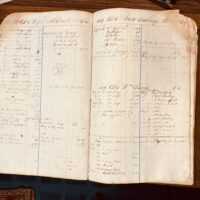

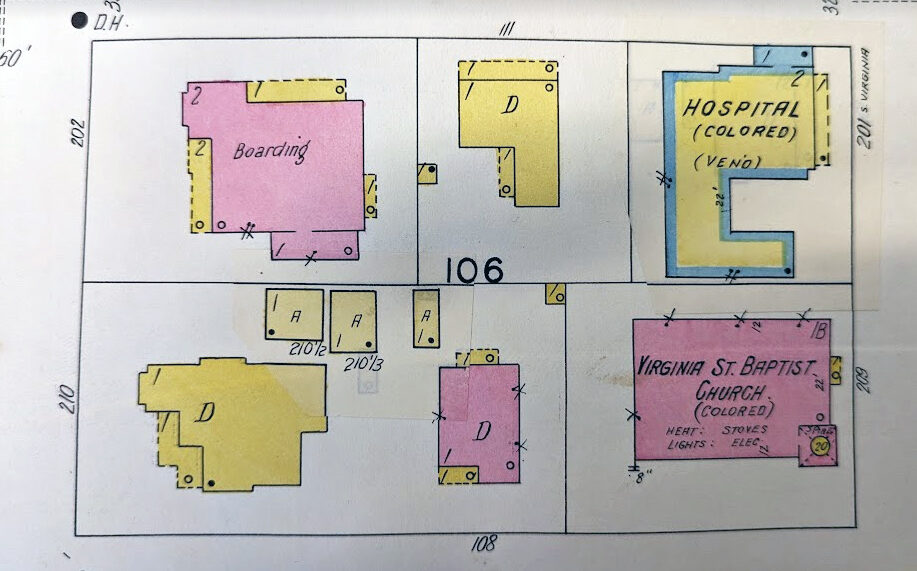

It was a small house, and the Postells set to work modifying and enlarging it. They continued this process for the next three decades. The Sanborn Fire Insurance maps, published every five to 10 years, provide a play-by-play guide to their renovations. By 1906, they had enlarged the front porch, added a back porch, and constructed an addition with a trendy octagonal bay on the southwestern side of the house.

By 1913, they had finished the attic as living space. They extended the northwest corner of the house and did away with their new back porch, replacing it with a little room. By 1923, this back room was gone. Maybe it was a temporary bathroom while they constructed a permanent facility within the house’s main body.

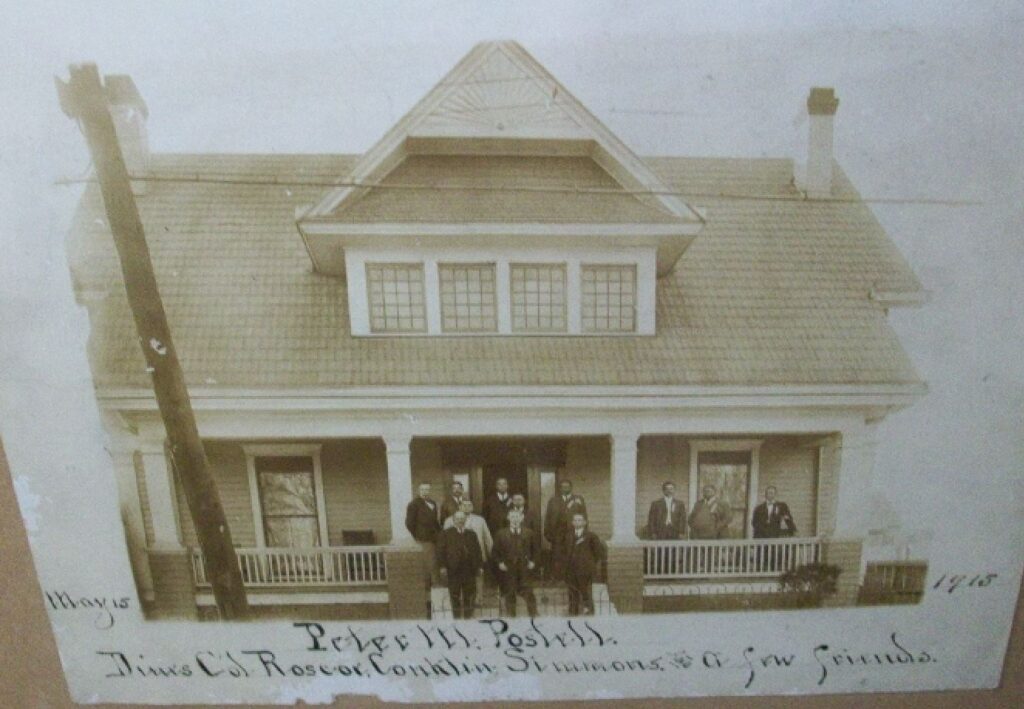

The photograph below from the 1910s shows 201 S. Virginia most of the way through the Postells’ transformation. The Eastlake decoration on the dormer’s gable betrays the fact that the house already had some years on it when the photograph was taken. Compared with a modern shot of the Brooks house, clues begin to emerge that indicate the buildings are one and the same. The placement of the windows, the massing of the bays, and that tell-tale jog in the eaves all help identify it.

201 S. Virginia was Peter Jr. and Fannie Postell’s home for nearly all of their married lives. Shortly before Peter’s death in 1944, they sold the property to Dr. Brooks.

But the Postells’ ownership isn’t the beginning of 201 S. Virginia’s story.

Andrew and Lizzie Sargent

The Postells were the first Black couple to own the property. They bought the house in 1894 for $1,200 from Dr. Andrew and Lizzie Sargent.

Andrew Sargent was born in Texas in 1858. His father had formerly lived in Christian County, briefly moved to Texas, and then thought better of it. Back in Kentucky, Andrew Sargent began medical training and graduated from Louisville Medical College in 1881. He returned to Hopkinsville and married Elizabeth Gish in 1883. The couple bought the house at 201 S. Virginia in 1887, though we don’t know if they lived in it.

Andrew and Lizzie Sargent divorced in 1896, two years after selling the house to the Postells. Ironically, Dr. Sargent married another divorcee also named Lizzie just weeks later.

Eliza A. Hayes

The story gets more improbable. The Sargents bought 201 S. Virginia from another divorcee, Eliza Hayes. While divorce wasn’t as absent in this period as many believe, it wasn’t common. It’s uncanny how many divorces are part of this house’s early history.

Eliza Wootton was born in 1833 to small farmers in Christian County. She married James Thomas Hayes in 1857. They moved to Cadiz, where James worked as a saddler. An apprentice and a 7-year-old enslaved girl also lived with them in 1860.

By 1870, James and Eliza Hayes had divorced. The details remain a mystery. Until after 1886, wives in Kentucky could only gain a divorce without their husbands’ consent on the grounds of cruelty. A husband, however, could divorce his wife at any time without her consent. The fact that Eliza kept custody of their son suggests the divorce was either mutual or instigated by her.

In 1870, James can be found living in a boarding house in Murray. Eliza and 9-year-old William lived in the household of Dr. Morton Powell in LaFayette. Eliza worked as the Powells’ housekeeper.

In 1879, Eliza Hayes bought her own house, 201 S. Virginia St. As a single woman and single parent in the Victorian South, Eliza’s financial independence must have been hard won and very sweet. Her status as divorced gave her more rights than married women in Kentucky at that time, who could not independently own property.

Hayes supplemented her income at 201 S. Virginia by taking a boarder, a white seamstress named Ann Lucas. Eliza also worked as a dressmaker. By 1887, she and her son had moved to Texas, and she sold the house to the Sargents.

B.F. Simmons

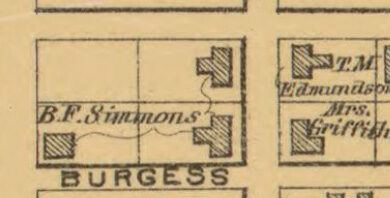

One year before Eliza Hayes bought 201 S. Virginia St., the Beers Company came through Hopkinsville and made a map of the city. This map shows the footprints of buildings, along with their owners’ names.

The Beers Map reveals that B.F. Simmons owned 201 S. Virginia. He also owned the rest of the block, which included a twin house next door at Virginia and Third, and a rectangular house at S. Main and Third.

In 1867, Benjamin Simmons and his wife, Dollie, bought the entire block from Main to Virginia and Second to Third (known as Jackson and Burgess streets, respectively, at that time) from Zechariah Glass. There was just one house on the property then, probably the house facing Main St. The Simmonses continued living at their homeplace further up on N. Main St. into the 1890s. It’s likely they purchased this block as an investment.

Benjamin Simmons was born in Virginia in the 1820s and moved to Christian County as a young man. He worked as an overseer, a wheelwright and eventually a carpenter. It’s likely he built the twin cottages at 201 and 209 S. Virginia himself as spec houses to rent or sell to Hopkinsville’s growing post-war urban population.

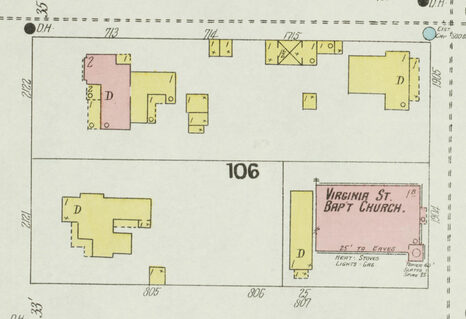

Whether Simmons rented out 201 S. Virginia before selling it to Eliza Hayes in 1879 remains unknown. He placed numerous ads in the newspaper for the rent or sale of the other cottage, 209 S. Virginia, throughout the 1880s, but nothing appears for 201 S. Virginia. By 1892, the cottage at 209 S. Virginia had been replaced by Virginia Street Baptist church.

A home and a haven

We’ve finally made it to the beginning of the story for the house at 201 S. Virginia St. A consistent vein runs through this house’s unexpectedly old story; that of how a house became both a home and a haven.

What a special legacy for a building.