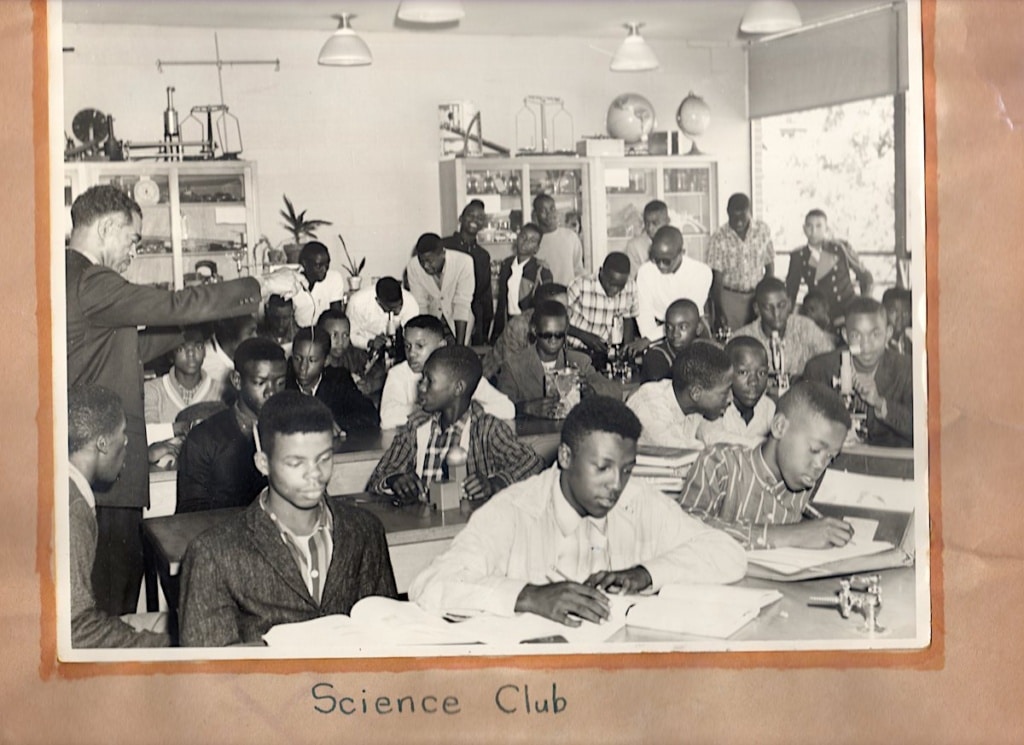

The classroom is filled beyond capacity as the photographer squeezes into a corner of the room to get as many people in the frame as possible. I can hear the sound of chalk on the blackboard, and I can smell wood shavings from an old school pencil sharpener. A few guys glance up to pose and smile. The photographer releases the shutter …

CLICK!

An educational moment is captured.

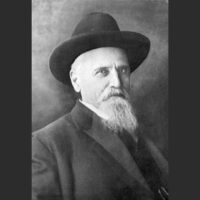

Today, we take a trip back to 1962 and directly into a classroom at Attucks High School. We are joined by no less than 30 young men and Mr. T.E. Withrow, one of the sponsors of the Science Club.

There is so much going on in this picture that one can get lost in its details. At least, I know I can. From the student wearing sunglasses in the middle of the room to the one intensely looking into a microscope in the back row, to the guy with his mouth hanging open in amazement on the very edge by Mr. Withrow to the smooth dude in his band uniform posing like a male model by the window — this photograph has more character and more life than many I’ve seen. It makes me want to know about each of these young men, their experiences in Hoptown, and where they are now. If you recognize someone, I’d love to know.

The fact of the matter is that I can’t identify anyone, except Mr. Withrow. Everyone else in the picture is simply a character to me. Characters full of stories and potential that grew out of a tightly knit and academically strong — yet segregated — school system and community.

Formal educational opportunities for African Americans in Christian County began in 1875 when a common school system for Black children was established. In 1916, local Black businessmen worked together to establish, fund and construct Attucks High School. The school was built at First and Vine streets to serve as the first — and only — four-year high school for African Americans in both Christian and Trigg counties. The founders chose to name the school in honor of Crispus Attucks, an African American Revolutionary War hero.

From its opening day on October 28, 1916, until the final class walked across the stage on May 29, 1967, Attucks served as an anchor in our African American community. Generations of students attended the school — many learning from the same teachers as their parents. The teachers and administrators were an active part of the community. I’ve heard former students reminisce about how you saw your teachers at school all week and likely at church on Sunday, making it tough to get away with, well, anything. There was a spirit of connectedness and community that supported these students in all they did, and that shows in the pages of the yearbooks and a few scrapbooks that the Museum is privileged to have.

This Science Club picture came from a scrapbook donated to the Museum by longtime, beloved educator Jennie Knight Baker. Created by students Robert Hudson and Roy Chester Garrott, the delicate pages feature projects spearheaded by the PTA and include pictures, newspaper clippings, programs from events and banquets, hand-drawn illustrations, and a surprising amount of glitter. Altogether, this scrapbook paints a picture of an active, well-rounded, multi-talented student body.

The Science Club was merely one of many activities available to the average Attucks student. This picture just happens to be my favorite. There was also the Glee Club, the “Le Cercle Francais,” and the New Farmers of America (NFA), to name a few.

The NFA was the African American counterpart to the Future Farmers of America (FFA) and was formed in 1935 to serve African American agriculture students in the South where schools were segregated. Attucks established its NFA chapter in 1939. The club picture in the 1962 yearbook is crammed with at least 70 male students, making it one of the largest chapters in the state and beyond. Harley Blane, a senior in 1962, served as the national president of the NFA that year. That’s a huge deal! The NFA and FFA merged nationally (and locally) in 1965.

The Attucks Wolves were well-known — even feared — in the area for their prowess in sports. The scrapbook dedicates pages to the football, basketball, and baseball teams — and to their respective cheerleaders and homecoming queens. The Wolfpack had taken home state trophies in basketball in 1947 and 1957, and the 1961-62 team took home the Seventh District crown with two players, David Brown and Lynn Shaw, making the All Second Region team. The program for the annual athletic banquet for all three sports found a home in the pages of this scrapbook, too.

And don’t let me forget the Attucks High School Band! Listed as “The Marching Hundred” in a candid photo in the yearbook, the band survives as one of the most remembered and loved traditions from the school. Of all the things that I wish I could go back in time to witness, the Attucks band is high on my list. I’ve heard stories of their talent and showmanship all my life and from people of all backgrounds in this town. It doesn’t seem like a parade was a parade unless the Attucks band — led by a squad of marching, twirling majorettes in fringed boots, short skirts, and tall hats — came down the street. It was a spectacle and a testament to the talent, skill, and dedication of the young musicians.

The band somehow evaded the pages of the scrapbook, but the majorettes made it with a glossy 8″x10″ portrait. Also finding their way into this time capsule was the program recognizing the 11 students who were inducted into the National Honor Society and a newspaper clipping about senior Sandra Yates who won the 1961 Voice of Democracy contest in Christian County and a superior rating in dramatic readings at the regional speech competition.

The students of Attucks High School did it all.

Beginning in the fall of 1963, the city and county school systems changed their policies to allow for voluntary integration for students at all grade levels. Until this time, the integration process had been implemented on a year-by-year basis starting in 1958 with the city’s youngest students. The Kentucky New Era reported that 21 African American students enrolled in Christian County High School the first year that they were allowed.

But until 1967, Attucks High School continued to provide quality education and opportunities for those who were left to attend. The last class graduated in May of that year, and in the fall, our school systems completely desegregated. Many expressed a sense of loss with the closing of Attucks.

In Chapter 52 of her memoir Bone Black: Memories of Girlhood, celebrated author and Hopkinsville High School graduate (Class of 1970) bell hooks writes:

“We cannot believe we must leave our beloved Crispus Attucks and go to schools in the white neighborhoods. We cannot imagine what it will be like to walk by the principal’s office and see a man who will not know our name, who will not care about us.”

The legacy of Attucks High School lives on today — in the accomplishments made within our African American community, in the obstacles overcome and expectations exceeded, and in the hearts and minds of all those who ever yelled “Do or Die for Attucks High!”

Now, it is our collective responsibility to remember, acknowledge and celebrate this legacy every time we cheer for our new consolidated high school’s Wolfpack.