The names are other-worldly, the stuff of mythology and science fiction. Cassiopeia. The Perseids. The Orion Nebula. The Andromeda Galaxy. For our ancestors, the celestial objects were map and calendar, reflected in western medicine wheels and eastern mounds. With modern GPS systems and atomic clocks, their importance has dwindled, but across the country interest in darker skies is growing. A rural movement to preserve and celebrate the natural night sky is gaining traction, and it’s offering environmental, health, communal, and economic benefits.

- RELATED: Visitors invited to see the beauty of darkness at Mammoth Cave National Park during Dark Sky Week

The plight of light pollution

A growing body of research reveals the harm of light pollution. It skews bird migrations. It diminishes sea turtle reproduction. It inhibits crop growth and strengthens insect populations. It negatively impacts human health, with possible links to sleep quality, systemic inflammation, obesity, breast cancer incidence, and diabetes. It wastes money and energy, contributing to climate change. Compounding the issue, light pollution is increasing at twice the rate of population growth worldwide.

There is also a growing movement against light pollution. Championed by dark sky advocates and bolstered by economic incentives, towns and parks around the globe are making strides to preserve night sky views. The International Dark-Sky Association (IDA) is the nonprofit lighting the way. It began 30 years ago in Arizona with two friends, an astronomer and a physician. Now it boasts a 66-chapter global network and hundreds of advocates working in their own localities to preserve dark skies.

The IDA is about education, promotion, and support for dark sky work, and its in-depth certification program identifies communities, parks, and sanctuaries around the world with dark skies. Interest is growing; the IDA is on track to exceed its number of annual certifications for the third straight year. To be clear, the list of dark sky places does not indicate the darkest spots in the world. The locales must meet a minimum darkness threshold, but more importantly, must demonstrate dedication to protecting the nocturnal environment. “Because of ongoing requirements, it takes a local pioneer or team that cares and wants to protect dark skies and create a sustainable plan to keep it going,” explains Bettymaya Foott, IDA’s Director of Engagement.

Building a Movement

Foott was in college, interested in the environment and sustainability, when she discovered dark sky work. “So many environmental issues are super politicized and depressing. Light pollution is a unifying issue,” said Foott. “It is the easiest type of pollution to fix.”

As a case in point, normally conservative Utah leads the country in dark skies advocacy. It has 27 certified dark sky places, the most of any state. The University of Utah offers a minor in Dark Sky Studies, and earlier this year legislators debated creating a dark sky license plate.

Foott says efforts in the state focus on the economic impact of dark sky tourism, a shared heritage of the night skies, and embracing the state’s primarily rural character. When the state legislature passed a non-binding resolution preserving night skies, she attended the legislative session. She noted, “All of the rural senators started arguing about who had the darkest skies. They had an inherent pride in it.”

Advocate Joyce Harman is working to build the movement across the country, in Rappahannock, Virginia. This little slice of rural landscape, with light encroaching from three sides, still retains a view of the Milky Way. It is another traditionally conservative area of the country, but Harman utilized her skill as a photographer to develop grassroots support.

Harman received a grant to photograph the night sky at people’s homes or tourism businesses, often featuring the Milky Way behind iconic structures in the county. The owners got a free picture to show neighbors and family.

“People just fell in love with it,” says Harman. “Now people are looking at the night sky, and it leapfrogged into a big conversation about it in the county.”

At popular night sky viewing events, Harman reached more people with the technology to take lunar pictures on their cell phones. “The first time, we had people lined up for two hours,” she says, noting that kids were insisting their parents wait in line. Thanks to the groundswell of interest generated by Harman and other advocates, the Rappahannock County Park achieved IDA Dark Sky Park status in 2019, one of the smallest ever certified at 7.3 acres.

Dark sky communities

Some dark sky advocates first grew interested in the cause because they were seeking a higher quality of life in their community. They wanted to eliminate glaring lights shining in their bedroom windows or keep their access to a dark night sky. Better outdoor lighting is often the first step, and it is a big piece of the IDA International Dark Sky Community certification. To qualify, locations must implement a lighting ordinance, provide regular educational programming, and demonstrate wide community support.

Updating street lights can be a complex process. Most communities in the U.S. do not own their own streetlights but lease them from their utility provider. The ability to install new fixtures hinges on cooperation between stakeholders.

Tiny Gilbert, Arkansas, with a population of 30 people, decided to upgrade its town lighting after a presentation by staff at the neighboring Buffalo National River. That was four years ago, and the town is awaiting a final decision by the state’s public service commission before they can finally install their 16 new lights.

Previous mayor Mitch Mortvedt led the effort. The town’s corporate provider could not offer them night sky friendly lighting at an affordable rate, and state law would not allow them to purchase their own fixtures. The community got their state senator, Missy Irvin, on board. She helped the town secure a special agreement from their electricity provider and win a grant for new fixtures. Tanko Lighting, which guides towns on municipalizing utility-owned street lighting, supplied information and advocacy.

The new lighting will use a fifth of the current energy use. “Other communities in the state want to go this direction and need an avenue,” says Mortvedt. “The smallest town in Arkansas is leading this charge.”

Torrey, Utah, population 240, became a certified International Dark Sky Community in 2018. They also had to navigate replacing their 22 rented street lights. Luckily, their electric cooperative was supportive of the efforts and restructured the town’s monthly rates to incentivize the switch to shielded lighting.

Advocates partnered with a local nonprofit and used a community crowdfunding site to purchase new fixtures. In four months, they raised $22,000, enough to replace the street lights as well as aid residents in changing their own lighting.

Mary Bedingfieldsmith is one of the advocates in Torrey. She notes that for some citizens, the dark is not a friendly place. Light provides a sense of security and the ability to work outside. Instead of talking about dark skies, she uses the terminology “night-sky viewing friendly.” That reframing and $900 in annual electricity savings brought most of the town on board with the project. Bedingfieldsmith shares her advice for other rural folks interested in dark sky work. “Find a cohort of like-minded people. Your shared concerns might not include IDA designation, but could be just education and showing people what they are missing.”

The Promise of Astrotourism

Many communities that achieve IDA certification are near certified parks and their dark sky status has an economic benefit as well. The growing field of astrotourism encompasses star gazing, as well as lunar viewing, and watching of eclipses, the northern lights, astronomical sites like Stonehenge, and meteor showers.

Due to its low population, plethora of public lands, dry climate, and high elevation, the Colorado Plateau has excellent dark sky viewing. According to a 2013 report on the economic impact of dark skies, night-focused tourism could generate 52,000 new jobs and $2.5 billion in the region in a decade.

The report highlighted two crucial benefits. Due to its nighttime nature, astrotourism necessitates at least one overnight stay. This can triple the economic impact of each visiting party. Second, dark sky tourism can be added to existing efforts in a way that fills open niches and maximizes utilization of current resources. Many parks have high visitation in the summer months; stargazing is often better in the fall, winter, and spring.

While dark sky tourism has exploded recently in the media, two popular tourist destinations say their nighttime appeal has slowly grown over the last five to 10 years.

Cherry Springs State Park in Pennsylvania was a little-visited state park until the 1990s, when amateur stargazers discovered it as one of the best places in the eastern U.S. for stargazing, thanks to its high elevation and the surrounding undeveloped Susquehannock State Forest. It became the first IDA International Dark Sky Park east of the Mississippi in 2008. The park staff works hard to preserve the resource, even working with oil and gas companies to time their flares to avoid star gazing events.

The park has limited facilities, all centered around the nighttime experience. There is a rustic campground and two astronomy areas: a permit-only overnight observation field for guests with their own equipment and a night sky public viewing area where they hold six nights of star programming each month.

Visitation has grown steadily in the last five years. In 2016, Cherry Springs had 68,000 visitors; this year it will exceed 100,000. One of their largest single events was the 2017 Perseid meteor shower. It coincided with a new moon, and over 1,600 people visited in just a few hours.

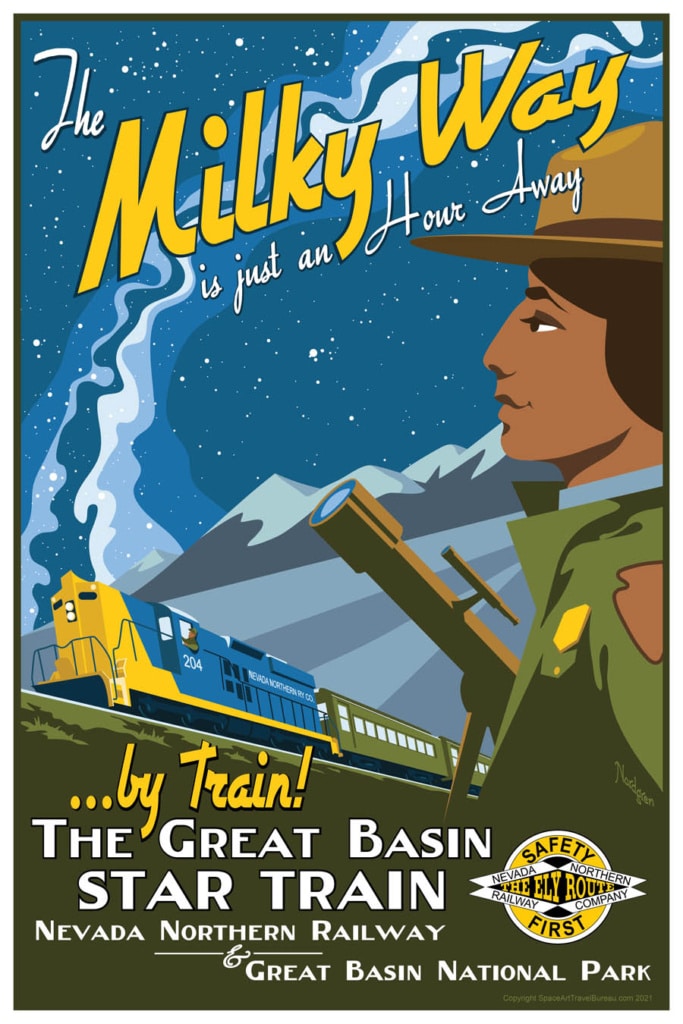

In Ely, Nevada, population 4,000, the Great Basin Star Train brings people from all over the world to this small mining town four hours north of Las Vegas. The Northern Nevada Railroad brings visitors to a remote viewing area in the Great Basin National Park, an IDA International Dark Sky Park, where rangers set up equipment to view and interpret the night sky. In 2014, the first year, two train trips carried 127 passengers. In 2021, their 47 train trips will carry 2,684 passengers. Its popularity boomed in 2019, when both CBS This Morning and a Las Vegas TV station arrived to film news stories on the same day. CBS reran the story on September 21, 2021, the day tickets for 2022 went on sale, and the entire 2022 season sold out in one day. According to Nevada Northern Railway President Mark Bassett, the Star Train created two full-time positions at the railroad and generates an estimated $724,000 annually for the local economy.

Tips for Viewing the Night Sky

If you want to see the Milky Way: Crescent moons provide a balance of earth and sky visibility. Summer viewing is the brightest, while it is most delicate in the winter. In the fall, it is visible for a period of time after dark.

If you want to see the moon and constellations: Bright full moons are the best bet for those with apprehensions about the dark or who want to go on a hike. Plus, the major planets and constellations are clear without so many other stars to overwhelm them.

Our Deep Connection to Dark Sky

Why do advocates around the world act as evangelists for dark skies? What inspires citizens to work doggedly for years to preserve a view of the Milky Way in their towns? Why do people travel across the country to spend a couple of hours viewing an almost-pristine starscape?

There is something elemental, even essential, about the natural night sky. Just like our ancestors who built architectural monuments to the solstice and wove stories of star-studded mythology, we need the cosmos. It reminds us of our place as infinitely tiny beings in the vast universe.

Mike McElhatton, educational program director at the Anzo-Borrego Desert National History Association in Borrego Springs, California, has experienced its power first hand. He has been leading monthly full moon walks for a decade in this IDA Certified Dark Sky Community and continues to delight in visitors’ responses of awe.

“It is bright enough to walk around at night,” says McElhatton. “People love it. It gives a feeling of the rest of the universe in a totally quiet environment and it is not something they have done before. The time of day creates an experience.”

I also experienced its power when I visited a park near me – Pickett-Pogue International Dark Sky Park in eastern Tennessee. We got a glimpse of the star-studded night sky while listening to coyotes howl in the evening and hearing neighbor’s accounts of bear sightings. It seemed that places with dark skies are also places where other kinds of wildness also roam free.

Andrew Tinsley of Knoxville camped near us, out with his family for a dark sky experience he had planned since rediscovering the night on a trip near Gunnison, Colorado. I asked him why it was important. “Big mountain ranges, grand canyons, and the night sky help us with perspective and we realize our own insignificance,” he said. “Seeing the stars is a spiritual experience.”

Tips for Dark Sky Friendly Lighting

The best outdoor lighting, according to the IDA:

• is on only when needed

• lights only the area that needs it

• is no brighter than necessary

• minimizes blue light emissions

• is fully shielded and aimed downward