This metal artifact appears both sweet and cold, precious and yet uncomfortable. It measures 36 inches tall, 18 inches wide, and 31.5 inches long. On casters to allow for mobility, this bed was meant for the tiniest and newest patients. The thin mattress provides some sense of warmth in this otherwise utilitarian piece of furniture.

This month’s artifact is a nursery bed from Brooks Memorial Hospital. It was donated to the Pennyroyal Area Museum by Cowan Brooks — one of Dr. Philip Carruthers Brooks’ sons — shortly after his father’s passing. The bed, along with many other items from the hospital, have been displayed at the museum for decades. That’s how important this story is to us. All of us.

Brooks Memorial Hospital

Dr. Philip Carruthers Brooks opened Brooks Memorial Hospital on South Virginia Street in 1944. Like the hospital’s founder, it’s primary patients were African American. Other hospitals in the area — including Jennie Stuart Memorial Hospital — did not provide treatment to people of color. Dr. Brooks opened this facility to provide quality medical care to a community in need.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. This article is the first in a three-part series that Jennifer P. Brown, Grace Abernethy and I wanted to share in honor of Brooks Memorial Hospital this Black History Month.

But this first column — much like the baby bed — is indicative of the beginning, long before the hospital existed.

Young parents of a future trailblazer

Henry and Carrie Brooks welcomed their first baby — Philip Carruthers Brooks — on Sept. 21, 1901. The couple had been married less than two years when he was born.

Henry Brooks

Henry Brooks was born about 1875 to Philip and Sarah (or Sally) Jackson Brooks. His parents married in Christian County in 1870, and by the 1880 census, they had three children: Nellie, Henry and Julia. The couple was not, however, living in the same household. Sarah Brooks appears listed as a widow or divorcee and working as a cook. She is living in the same house with a woman named Lucy Jackson, who I assume was her mother.

I found a second Sarah Brooks listed in the same census who was also a cook and of a similar age. She appears as a divorced or widowed woman living and working in the household of Edmund A. Starling, a white man who had served in the U.S. Army during the Civil War.

These two Sarahs may be the same person who was counted on the census twice — once at home and once at work. I honestly can’t be sure. I was unable to find any other reference to Sarah or her husband, Philip, after 1880.

Carrie (Haynes) Brooks

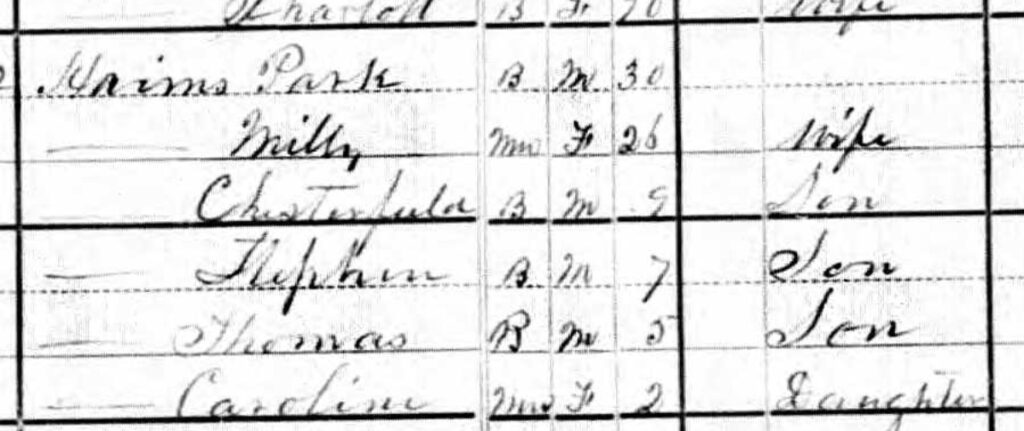

Carrie, or Caroline, Brooks was the daughter of Park and Millie Haynes and was born about 1878. Her father worked on a farm, and, in 1880, she had three older brothers. Like her husband, Henry, she is identified as “mulatto.” This designation was likely given by the census taker based solely on their light complexion.

A flourishing community

As young parents, Henry and Carrie Brooks named their first born after his grandfather, a tradition that will be passed down time and time again in the Brooks family. Philip was the first of at least nine — though, some sources say as many as 13 — children born in this family. Accessible records provided the names of eight. The Brooks children were Philip, Hugh (or Hughintis), Henry Leslie, Julius, Garland, Paul, Sarah and Charles. A stillborn baby was the final child born to the family.

Henry Brooks worked a variety of jobs throughout his lifetime. I found him listed as a porter or janitor at a store and at a barbershop, as a cook at a hotel and as a carpenter. He and his wife were both literate, and they owned their home in the tightly-knit neighborhood on the east side of Hopkinsville. Plotted in the late 1890s, this area was largely developed and settled by the growing African American middle class of the early 20th century. Black-owned businesses, churches, stores, professional offices and houses lined the streets of this area of town.

And the Brooks family was in the heart of it.

Although the 1910 census places the family on Broad Street, the Hopkinsville City Directory of the same year shows their address on East Fourth Street, somewhere between Campbell Street and Adams Lane. It appears that their homeplace stays here for the next couple of decades.

The Hopkinsville in which Philip Brooks and his siblings grew up provided them with many examples of professional success. The first Black physician to open a practice in Hopkinsville was Dr. Joseph C. Lyte in 1893. By 1910, there were four Black doctors here: Drs. Lyte, Duncan, Flemister and Leverett. By 1916, the number had increased to five (Drs. Berry, May, Duncan, Flemister and Moore), with 11 Black women listed as nurses in the city directory. The community also had a Black dentist, Dr. M.A. Melton, and three practicing Black attorneys that year.

That is just a glimpse into the professional sector of Hopkinsville’s African American community of the early 20th century, and what a distinguished community it was!

The Brooks family suffered a great deal of loss in a relatively short period of time. Sarah, the only daughter, was born in 1918. Her oldest brother would have been a student at Attucks High School at the time. Little Sarah contracted diphtheria and died on Sept. 27, 1920. She was only 3 years old. Her younger brother was almost 3 months old.

In July 1922, Carrie gave birth to a stillborn son. A week later, she died after developing an infection during childbirth. She was only 42 years old, and she left behind her husband and seven sons who ranged in age from 2 to 20.

Five years later, on Nov. 20, 1927, Henry Brooks succumbed to stomach cancer at the age of 53. They are all buried at Cave Springs Cemetery.

A young patriarch

Dr. Philip Brooks was only 26 years old when became the patriarch of the Brooks family as the oldest of the seven brothers. He had just completed medical school at Howard University.

I’ll leave the rest of Dr. Brooks’s story for Jennifer to tell. Here’s what became of his brothers.

While none of them used the nursery bed from Brooks Memorial Hospital, it symbolizes a family’s infancy that grew into a long, strong legacy — one the museum is proud to share.

Hughintis Thomas Brooks

Hughintis Thomas Brooks, the second son, was born on Oct. 17, 1904. Hugh moved north to Detroit and frequently provided a home for his younger brothers looking for work. At varying times, Henry, Paul and Charles lived in the Motor City. Hughintis stayed there for the duration of his adult life and worked in the automobile industry. He married Linden Brooks and died on Jan. 23, 1972. His body was returned home to be buried in Cave Spring Cemetery.

Henry Leslie Brooks

Henry Leslie Brooks was born on June 27, 1905, and followed his oldest brother Philip to Howard University, where he graduated from pharmacy school in 1928. According to his obituary, he practiced in Detroit before moving back to Hopkinsville to open Brooks Brothers Pharmacy with his younger brother Garland in 1935. He died of cancer of the larynx on Nov. 24, 1952, when he was 47 years old. He was survived by his wife Bernyce and a son named Hughintis. He is buried in Cave Spring Cemetery.

Julius Caesar Brooks

Given the name of a Roman emperor, Julius Caesar Brooks was born on Feb. 1, 1910. He married Parmis Blane between 1930 and 1935. The 1935 Hopkinsville City Directory lists them at the Brooks homeplace on Fourth Street. Julius was the co-owner of Brooks & Harris, a taxicab company that operated at 500 S. Virginia St. Parmis was employed at the Baus Glove Factory on First Street. He worked at a hotel in the 1940s and was listed as a laborer at Fort Campbell in the 1950 census, while Parmis worked as a cashier at a local theater. He worked as a bartender at the NCO Club in the 1960s. Julius died on May 9, 1969, at Brooks Memorial Hospital after a prolonged illness and is buried at Cave Springs. He was survived by his wife, who died in 1986, and his daughter Carolyn.

Garland Harris Brooks Sr.

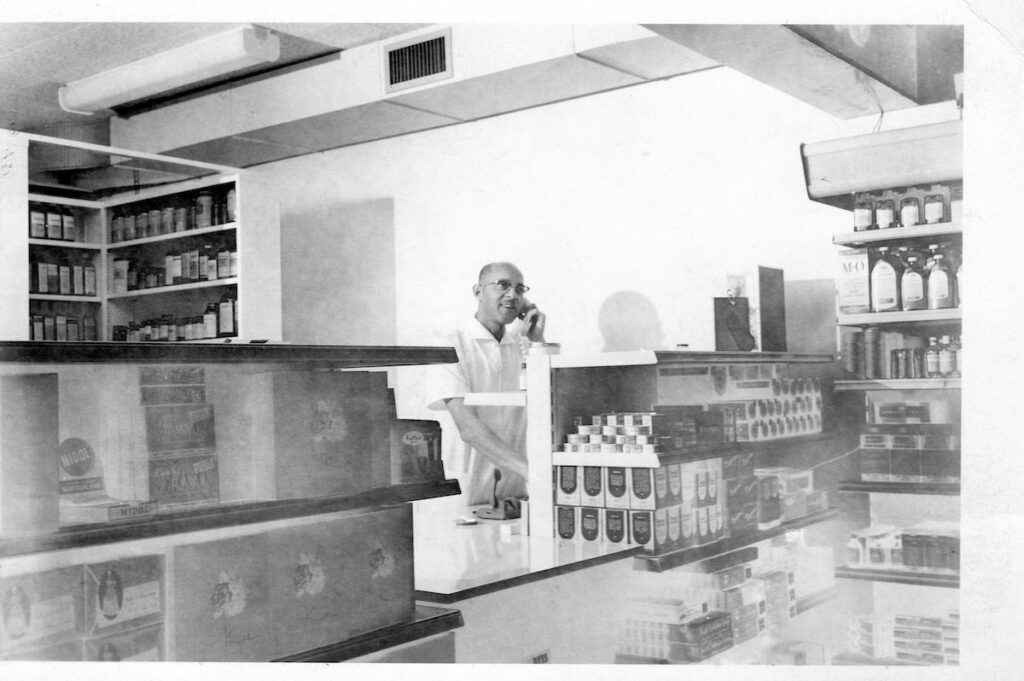

A Christmas baby, Garland Harris Brooks Sr. was born on Dec. 25, 1912, and was only 14 years old when his father died. The 1928 city directory lists him as employed as a porter at the OK Barber Shop — the job his dad held at the time of his death. Garland attended Howard University and graduated from pharmacy school in 1934. He returned to Hopkinsville to open Brooks Brothers Pharmacy in 1935 with his brother Henry. The pharmacy was originally located on South Virginia Street — next door to the Brooks Brothers Pool Room — until the well-known Brooks building was constructed on Fourth Street in 1959. Garland married Sara Melton Brooks (the daughter of Dr. Melton, the dentist), and they raised five children. He died on Aug. 9, 1984, and is buried at Cave Spring Cemetery.

Paul DeWayne Brooks

Born on July 13, 1913, Paul DeWayne Brooks attended Kentucky State University after graduating from Attucks High School. He worked for National Carbide in Louisville before returning to Hopkinsville to open and manage the Club Louisvillian. He also worked as a bank courier for old Planters Bank. The museum is lucky to have a copy of his funeral program, which lists his four wives and four children. He lived in Louisville when he died on April 24, 1997. Like many of his brothers, he is also buried at Cave Springs Cemetery.

Charles Osman Brooks

Charles Osman Brooks, the youngest of the brood, was born on July 4, 1920. After his father’s death in 1927, he lived with his aunt Nellie Lowery on Thompson Street. Her husband Wyley died a few years earlier. He was raised in this home with his aunt and cousin Hazel, also a widow who worked as a teacher. In 1940, Charles was employed as a clerk at a drugstore (I’m guessing with his older brothers), but he moved to Detroit by 1942 to live with his brother Hugh. He was working in the Sears-Roebuck Warehouse when he registered for the draft in World War II. He served as a Private First Class in the U.S. Army from Dec. 30, 1942, until he was discharged on Nov. 14, 1945. He married Shirley Ann Hanley, and they had three children. He appears in the Hopkinsville City Directory consistently in the 1950s and ‘60s, when he worked as a medical technician at Brooks Hospital. Charles Osman died on Feb. 5, 1980, and is buried at Cave Springs Cemetery.

Alissa Keller is the executive director of the Museums of Historic Hopkinsville-Christian County. She’s a graduate of Centre College with degrees in history and English and of Clemson University/College of Charleston with a master’s degree in historic preservation. She serves on the Kentucky Historical Society and the Kentucky Museum and Heritage Alliance boards.