On June 30, 1924, the Dalton house changed hands for the first time. Trustees of Hopkinsville’s First Methodist congregation purchased the home from Monroe and Carrie Dalton for $10,500. For the next three decades, the Dalton house served as the church’s parsonage.

The original owners, Monroe and Carrie Dalton, moved into a brick bungalow they had built on North Main Street outside the city limits and close to the brickyard. With his brother George’s death a year and a half earlier, Monroe was now the president of Dalton Bros. Brick Co. His primary job had always been to manage daily operations at the brickyard, and presumably that had not changed with his new title. Both Dalton daughters were now married and out of the house. Monroe and Carrie Dalton decided the time had come to downsize.

The feel of daily life at the house would change forever with the Daltons’ departure. For one thing, gone were the days of hired domestic staff in the house. Over the next 28 years, seven Methodist ministers and their families lived at the East Seventh Street house. The ministers’ wives assumed the jobs of cooking and cleaning.

The year 1924 also saw another symbolic change — the house’s address became 713 E. Seventh St., the number it bears today. Prior to this, it was 615 E. Seventh St.

Three churches for the Methodists

First United Methodist Church has deep roots in Hopkinsville. Its current building on South Main Street was built between 1917 and 1919 and is one of downtown’s most iconic buildings. But did you know this is the congregation’s third location in the city?

The First Methodist congregation was organized shortly after 1800, making it one of the city’s oldest institutions. In the early days, itinerant preachers cycled through Hopkinsville, teaching at church members’ homes and the courthouse. It wasn’t until about 1818 that the Methodist congregation built its first meeting house. This was on Fifth Street, then known as Market Street. In 1846, they expanded by building a brick house next door to serve as the parsonage.

But by this point, the meeting house was dilapidated and the neighborhood around it had shifted from residential to industrial. There was at least one smelly tanyard in close proximity, as well as a brickyard and a tobacco stemming factory. The church decided the time had come to look for a new location.

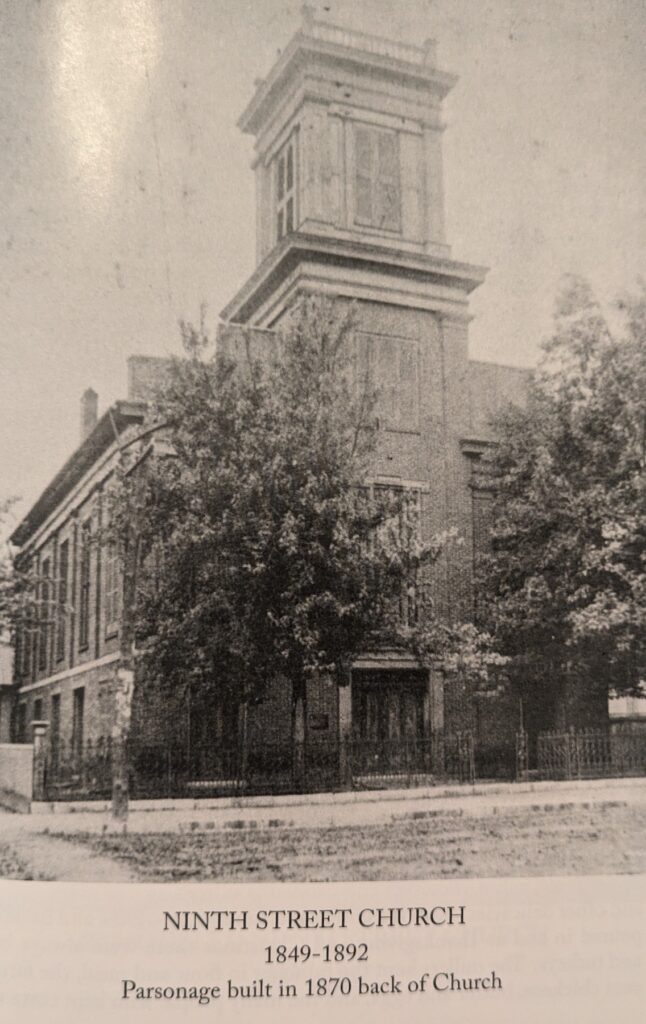

They sold the parsonage in 1848 and the church in 1849 and began construction on their second church building, located at Clay and E. Ninth streets. The congregation occupied this location for 70 years, until the completion of their current building in 1919.

A popular parsonage

I was initially a bit puzzled as to why the Methodists wanted the Dalton House for their parsonage. Granted, it’s a nice house (in my opinion), but it’s a good 12 blocks from the church building. It turns out this very attribute was one of the key reasons the church board thought the Dalton house so well-suited for the parsonage.

In 1870, when the Methodists had been on Ninth and Clay for about 20 years, they built a new parsonage. It was a brick cottage, located on Clay Street, conveniently close to the church. In fact, it was so convenient and so close it almost immediately began causing problems.

Some church members saw the Clay Street parsonage as an extension of the church facilities. They particularly appreciated the parsonage’s bathroom, something the church building lacked!

The result was a steady flow of people through the parsonage during church services and events. Aside from the general use of the bathroom facility, nursing mothers also frequented the couches in the parlor. At any point, the minister might return home to find his toilet, sofas and chairs all occupied.

He seems to have accepted this situation graciously. But in 1924, the trustees of First Methodist decided that separating the church and the parsonage with the distance of a healthy walk through downtown and across the railroad tracks was not a bad thing. You have to wonder if the 1870 parsonage came to mind!

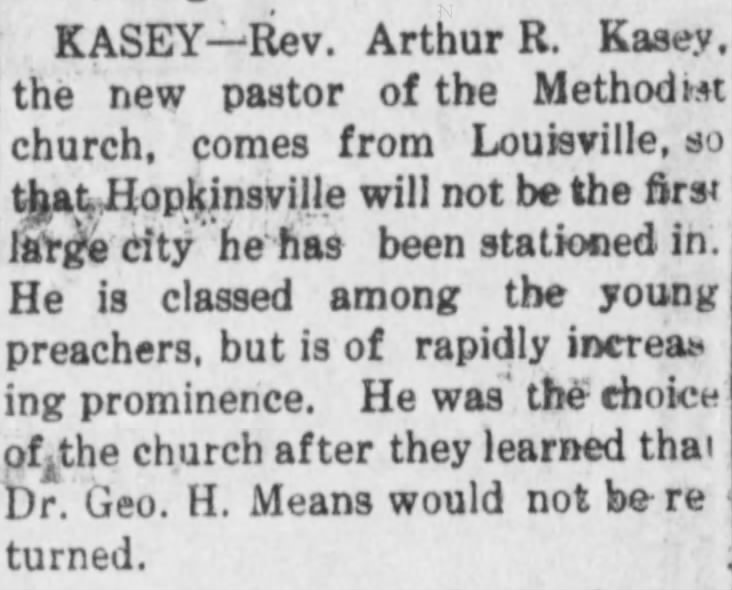

The Rev. Arthur Kasey

The first minister to occupy the new East Seventh Street parsonage was the Rev. Arthur Kasey, who was beloved by the Hopkinsville First Methodist congregation and served four separate terms as their minister. Kasey actually lived in the Dalton house twice, first in 1924 and again from 1938-1943. Methodist ministers were assigned four-year terms and were shuffled about frequently.

Kasey and his family, however, formed a deep connection with Hopkinsville. Kasey first came to Hopkinsville in 1910, at the age of 38. His wife, Lavinia, their two small children, Ruth and Arthur Jr., ages 3 and 1, respectively, and his widowed mother Martha rounded out the household.

Kasey was born in Breckenridge County, Kentucky, into a farming family that produced not one, but two Methodist ministers. The family relocated to Owensboro, where Kasey spent most of his growing up years. He saved his money and paid his own way through the Elkton Training Institute then entered Vanderbilt University, graduating in 1901. His first church assignment was in Burkesville, Kentucky. In this church, he met a young woman named Lavinia Ray, who he eventually married.

But before this happened, Kasey took a far-flung church assignment as pastor of Grand Street Methodist Episcopal Church in Helena, Montana. He remained here for 1904 and most of 1905. He returned toward the end of the 1905 and married Lavinia Ray. But there’s more to it than that.

The First Methodist Church has a well-documented pamphlet concerning their history with quite a bit of biographical information about the pastors. But there’s only one paragraph concerning the ministers’ wives, which begins with, “Nothing has been said of the preachers’ wives, the charming and lovely women who graced the parsonages.” I think it’s true that these women probably spent more time in our house than their husbands, and I was curious about them.

So I searched for more about Lavinia’s story.

Lavinia goes to Montana

What makes Arthur Kasey’s Montana interlude so interesting is that Lavinia too had ties to Helena, Montana. In October 1896, the Nashville Banner newspaper reported that 16-year-old “Miss Lavinia Ray, of Edmonton, Kentucky, who has been visiting her aunt, Mrs. J.O. Cheek of Woodland street, left this morning for Helena, Montana, where she will spend the winter with Mrs. C.C. Newman.” This innocuous little article throws wide a window into a teenage girl’s world turned upside down.

Why was Lavinia being shuttled all over America in 1896?

A well-connected family

Mrs. C.C. Newman was Julia Ritchey Newman, Lavinia’s mother’s youngest sister, who was just seven years older than Lavinia herself. In 1893, Julia married an up-and-coming Kentucky attorney named Cephas Newman, who had relocated to Helena, Montana and was making a good name for himself. As a timely side note, C.C. Newman’s brother was the Secretary of the Kentucky State Fair in the early 1900s.

The other aunt mentioned in the article is Mrs. J.O. Cheek of Nashville. This was Amelia “Minnie” Ritchey Cheek, another younger sister of Lavinia’s mother’s, and she was married to Joel Owsley Cheek, a Burkesville native who had made a big name for himself in Nashville. J.O. Cheek had gone into the grocery business with his cousin Christopher Cheek (the builder of Cheekwood in Nashville) in the 1880s. He had concocted his own special blend of coffee, which he had convinced the Maxwell House Hotel to serve exclusively. You’ve probably had a cup of it. It came to be known as Maxwell House Coffee.

One of Julia and Minnie’s brothers, J.H. Ritchey, used his family connection to the Cheeks to create business opportunities for himself in Nashville. He opened a grocery store in Burkesville around 1910 but did his wholesale buying in Nashville.

A Kentucky tragedy

And then there was Lavinia’s mother, Elizabeth. Mary Elizabeth Ritchey was the oldest child of James and Helen Ritchey. She married Nicholas Ray in 1875, a farmer from Edmonton, in neighboring Metcalfe County. The 1880 census lists him as a stock trader in Burkesville. They had two daughters, Laura and Mary Lavinia, named after Nicholas’ mother. The documents pertaining to the family are scant. By 1896, we know through the Nashville Banner article, that they had moved to Edmonton, Nicholas’ hometown.

In Edmonton, things went horribly wrong. The details are vague to non-existent, but what’s clear is that Nicholas Ray killed a local attorney named Albert Scott in 1896. In August, while Nicholas was being held in the local jail, a mob attempted to break in and lynch him. The jailers were able to stop the mob, but they found Nicholas huddled in the corner of his cell clutching a rock he had frantically pried free from the wall to defend himself. After this, he was transferred to Glasgow for his own safety.

I would guess it was sometime during this progression of events that Lavinia was sent to Nashville to stay with her rich, respectable aunt. And when October rolled around, the family decided it was still too soon for her to return home, and she was sent to Montana for the winter.

I could only find the single newspaper article about Nicholas Ray. But he must have been found guilty of some crime because the 1900 census lists a Nicholas Ray of his age in the state penitentiary in Frankfort. By 1910, he had been released, and the family moved to Florida, where they stayed for the rest of his life.

Beloved church leaders

I don’t think Lavinia ever lived with both of her parents again after 1896. Records don’t show where she went after returning from Montana. We know she was back in Burkesville around 1901 because this was when she met Arthur Kasey. Perhaps she was living with extended family.

On Oct. 11, 1905, Lavinia Ray and Arthur Kasey married where their story began, in Burkesville, Kentucky. The Helena Record-Herald in Montana ran a lengthy article on the event. More than just “graceful and charming,” Lavinia Ray must have been tough to live through these traumatic events at so young an age. And more than just making it through, she thrived, moving past the past to shape a full life and future for her nuclear and church family.

Arthur and Lavinia Kasey spent a total of 17 years at Hopkinsville First Methodist and are remembered as foundational and beloved leaders. At their deaths, both were laid to rest at Riverside Cemetery.

Grace Abernethy is a historic preservationist and artist who specializes in caring for and recreating historic architectural finishes. She earned her Master of Science in Historic Preservation from Clemson University in 2011 and has worked on historic buildings throughout the eastern United States. Abernethy was a recipient of the South Carolina Palmetto Trust for Historic Preservation Award in 2014 and won 2nd place in the Charles E. Peterson Prize for the Historic American Buildings Survey in 2011. She and her husband, Brendan, moved to Hopkinsville from Nashville in 2020. She works as an independent contractor and is a board member of the Hopkinsville History Foundation.