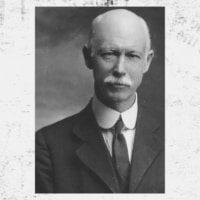

Historians have remembered Confederate Col. Thomas Woodward, of Hopkinsville, mainly for two episodes during the Civil War. In the first one, he used a fake cannon made of logs to outwit federal troops and regain control of Clarksville, Tennessee. In the second case, he was shot dead while on his horse at Ninth and Main streets in Hopkinsville.

Woodward was born in a northern state in 1828 and moved to Kentucky when he was about 20 years old, reportedly after attending West Point. He joined the Confederates at the start of the Civil War but was removed from his command at various times for insubordination and periods of drunkenness.

A wooden cannon

On Aug. 18, 1862, Woodward was outnumbered when he helped lead Confederates to Clarksville, where federal troops had control of the city and the Cumberland River, according to William Henry Perrin’s “County of Christian, Kentucky,” published in 1884. Woodward’s men used black paint to disguise logs as a cannon on wheels and forced a quick surrender from Union Col. Rodney Mason.

When Mason was captured and saw that Woodward was so petite that his riding boots came well above his knees, he reportedly broke into laughter and begged the Confederate colonel to pose for a photograph at a studio in Clarksville.

“I want to send it up North to my friends to let them see what a d—– insignificant cuss I surrendered to,” Mason said, according to witnesses who described the scene that was recounted in newspapers across the country.

Woodward obliged, and the photograph was made.

Outnumbered and drinking

Two years later, on Aug. 19, 1864, Woodward got the best of himself with a bad decision. Hopkinsville was under federal occupation at the time, and Woodward was hell-bent to take the town back as he rode into Hopkinsville with a small band of rebel soldiers.

This account, included in Charles Meacham’s “A History of Christian County, Kentucky: From Oxcart to Airplane,” published in 1930, describes the scene:

“He came in from the South and at the corner of Main and Fifteenth Streets the small number of men with him halted and refused to follow him. One man rode with Woodward, who was under the influence of liquor, and endeavored to dissuade him from the foolhardy undertaking, as the windows along Main Street were filled with armed men. This man finally stopped and Woodward rode slowly down the street to within a few paces of Ninth Street, when he was commanded to halt. He stopped his horse and was in the act of raising his pistol to a window … when a volley was fired at him from the windows of the building on that corner and from the upper windows of the Phoenix Hotel, and other nearby buildings. One bullet struck his horse in the neck and four entered the body of the rider. The horse sank to the ground and Woodward was picked up and carried into the office of the hotel, where he expired within a few minutes.”

By the turn of the 20th century, Woodward was being described as a hero among Confederate veterans and their supporters.

Memorial fountain

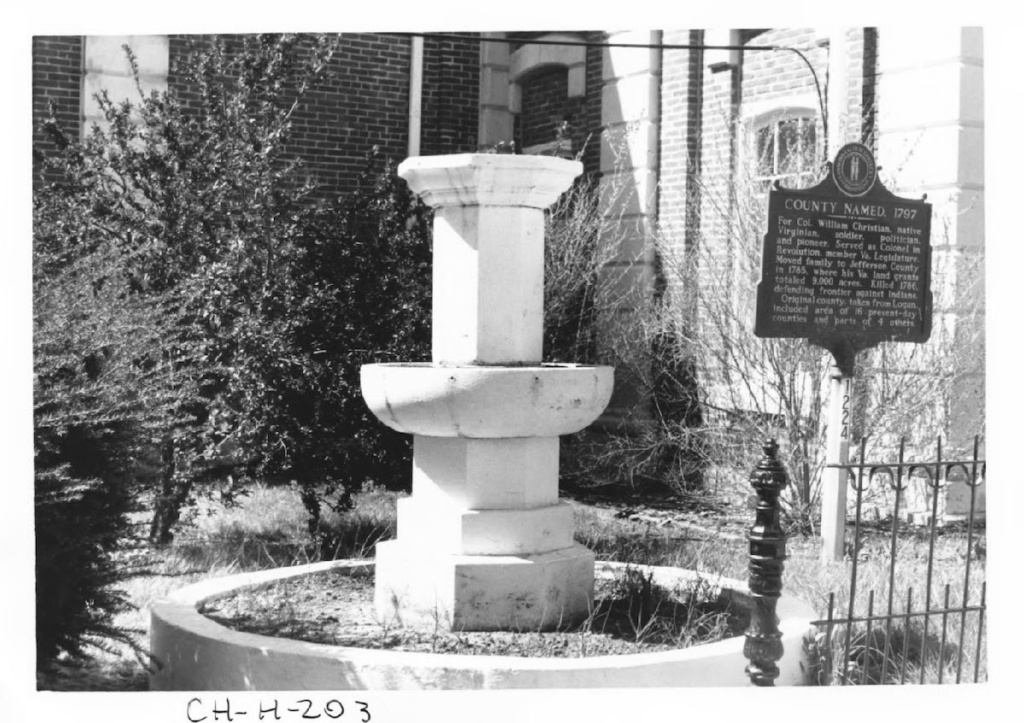

Forty years after the colonel’s death, the United Daughters of the Confederacy had a drinking fountain placed at Ninth and Main streets in his memory.

A story about the memorial fountain, published in the Sept. 23, 1906, edition of the Courier-Journal in Louisville, called Woodward “dashing and fearless.” The story listed Woodward as a West Point graduate. Other accounts said he was booted out of the military academy. Woodward was “erratic” but also proved to be one of the “bravest and most gallant soldiers,” in service to the Lost Cause, the story claimed.

The Lost Cause is an ideology that gained favor in the South following the Civil War. It held that the Confederates had been in an honorable struggle against Northern aggression and that loyal Confederates fought to preserve a way of life and for states’ rights rather than the right to keep slavery legal. Many Confederate memorials were erected in support of the Lost Cause ideology. Today, most academic scholars and historians regard the Lost Cause as a myth that took hold as Confederate veterans were aging and then continued as an attempt to counter to the Civil Rights Movement.

The drinking fountain erected as a memorial to Woodward is now on the front lawn of the Christian County Courthouse. It has not held any water in decades.

Jennifer P. Brown is co-founder, publisher and editor of Hoptown Chronicle. You can reach her at editor@hoptownchronicle.org. Brown was a reporter and editor at the Kentucky New Era, where she worked for 30 years. She is a co-chair of the national advisory board to the Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues, governing board past president for the Kentucky Historical Society, and co-founder of the Kentucky Open Government Coalition. She serves on the Hopkinsville History Foundation's board.