Land Between the Lakes would be guaranteed at least $8 million in federal funding annually if Congress passes legislation introduced Tuesday by Republican co-sponsors Sen. Mitch McConnell and Rep. James Comer, who said in a press release that the plan is designed to protect LBL’s natural heritage.

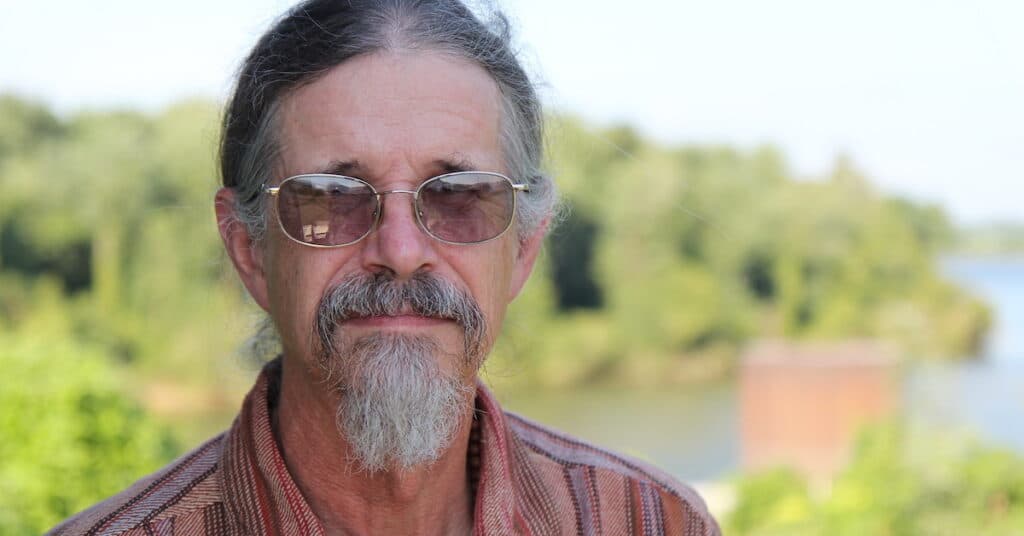

Among those who back the LBL Recreation and Heritage Act is David Nickell, 65, of Eddyville, a philosophy and sociology professor at West Kentucky Community and Technical College who also farms. Nickell has been advocating most of his life for former residents of the region who want to preserve the natural resources and history of the 171,280-acre peninsula stretching from Western Kentucky into Northwestern Tennessee.

In 1967, when Nickell was 10 years old, his family was forced to sell a farm between the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers that they had owned since the 1780s. The removal of hundreds of families from the region cleared the way for the Tennessee Valley Authority to develop LBL after dams had been constructed on the two rivers to create Kentucky Lake and Lake Barkley.

“TVA used every means at its disposal to remove any evidence that we ever existed, and they did this for a specific promise of what Land Between the Lakes was going to be like,” Nickell told Hoptown Chronicle.

The promise from TVA, that Nickell and others have described for years, was that LBL would never be commercialized. Outdoor enthusiasts would be attracted by its natural beauty, which would in turn boost the economies of communities in the counties surrounding the area.

“They paid us almost nothing for our land. People who resisted, they bulldozed their houses and burned them. They bulldozed our churches. Everything,” said Nickell, who is president of Between the Rivers Inc. The group works to maintain more than 250 cemeteries in LBL and advocates for heritage improvements such as maps that show the location of communities that used to exist in the region.

The LBL Recreation and Heritage Act is “a step toward rectifying that … and of finally trying to take steps to make LBL be what it was originally intended to be.”

This is Nickell’s second experience with federal legislation that attempts to put LBL on sound financial footing while also addressing complaints that a federal agency responsible for its management is not keeping promises made to the families when they had to sell their homes and leave.

In the mid-1990s, TVA released several concepts for the possibility of generating income at LBL. These included suggestions for theme parks, resorts and residential income. Public opposition was swift, and TVA did not pursue development. But then Craven Crowell, who was TVA’s board chairman, abruptly announced the federal agency would not request funding for LBL after fiscal year 1998.

Ed Whitfield, a Hopkinsville Republican who represented the 1st Congressional District in which Comer now serves, began holding meetings with former residents and others interested in LBL, and he helped bring a congressional hearing to the region.

“It no longer belongs to us, but we still belong to it.”

– David Nickell, on the farmland between the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers that is now Land Between the Lakes

On June 21, 1997, the U.S. House Subcommittee on Water Resources and Environment conducted a hearing in Murray State University’s Lovett Auditorium.

On that day Nickell told the committee he had been waiting 30 years for the chance to explain the “sacred place” that was taken from his family and many others when the federal government created a national recreation area from thousands of acres of forest and farmland between the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers.

“It no longer belongs to us, but we still belong to it,” he testified. “Our identity is tied to it in ways that we do not understand. I ask you how many generations must a people live in one place before they become the native offspring of that place? It is not property to us. We belong to it more than it ever belonged to us.”

Congress passed the LBL Protection Act in 1998, and the following year LBL was transferred from TVA to the U.S. Forest Service, which is part of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

In the past year to 18 months, the Forest Service has looked at reducing some operations. For example, in December 2020 officials said The Homeplace, a working 1850s farm and living history site, would see a reduction in staff and operations to offset expenses. But after backlash from community members in the region, the agency said The Homeplace would not face any reductions in 2021.

If the new legislation from McConnell and Comer passes, Nickell believes it will be a “big improvement” for LBL.

“What these amendments do is mandate how much money LBL is going to get and what it can be used for, and this should really increase the emphasis on environmental education and outdoor recreation, so that Land Between the Lakes can be managed as a recreation area and not just a normal Forest Service unit,” he said.

“I think it is the best chance we’ve had for LBL to finally become the premiere recreation area that it should have always been. And I’m also excited because it does elevate the status of the heritage program,” he said.

One obvious difference between the passage of the LBL Protection Act in 1998 and the effort to pass new legislation in 2022 is the number of former residents who are still here to advocate for it.

“There are fewer of us all the time, but there are still quite a few here, and we are trying our best to raise our children and grandchildren to care about the place, too,” said Nickell.

Former residents envision a heritage program that puts back something that TVA worked so hard to remove — evidence that families once lived and thrived between the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers.

“We want to have heritage trails that show where things were located … and the stories associated with them,” Nickell said.

A mistake about the acreage of LBL was corrected in this story.

Jennifer P. Brown is co-founder, publisher and editor of Hoptown Chronicle. You can reach her at editor@hoptownchronicle.org. She spent 30 years as a reporter and editor at the Kentucky New Era. She is a co-chair of the national advisory board to the Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues, governing board president for the Kentucky Historical Society, and co-founder of the Kentucky Open Government Coalition.