I’ve been on the road for the entire month of April. My time as an itinerant worker has brought to mind a significant group of people who lived at 713 E. Seventh St. that I haven’t mentioned yet: the boarders.

You’ve probably never thought about Airbnb as a return to something old. In a way it is. The company was started recently, in 2008, and different cities have come up with their own regulations for it. The model Nashville pushes is an Airbnb in which the owner lives full-time while renting out a room. This reminds me of a return to the historic housing trend that, until recent history, was quite common.

Hodge-podge historic households

The single-family household became the dominant housing form in American society relatively recently. The historic household was far more eclectic, made up of immediate and extended family members, people who did labor for the homeowner, and lodgers.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it was normal for homeowners with extra space to take on boarders. Boarders paid by the week or month and usually got a bed and meals. This allowed a homeowner to earn a little extra cash to make ends meet. It could also justify paying a cook or maid, resulting in a higher standard of living for the family.

Boarders came from all walks of the population, but in upper-middle class households like the Daltons’ they tended to be male professionals. Boarding was a good way for a young man to save money towards marriage and buying his own house. Conversely, some bachelors remained boarders for their entire lives because of the ease of having someone cook and clean for them.

Hopkinsville boarders

In 1910, Hopkinsville’s population was 9,419. The census for that year lists 699 people as lodgers, boarders, or roomers. That’s 7.4% of the city’s population. Census-takers sometimes listed relatives whose familial relationship was too complex to succinctly fit into a box as boarders or lodgers. So some of these 699 may be relatives. But the majority were likely true boarders.

The Daltons seem to have always had boarders at their Seventh Street residence. In 1910, Dennis Shaw and Thomas Lynch boarded with them. The men may have each had their own room, but I think it’s more likely that they shared a bedroom. Shaw and Lynch were both middle-aged professionals. Shaw was 35 in 1910 and a bookeeper at a bank. A life-long boarder, he lived with the Daltons for at least seven years. Lynch was 40 and the superintendent of Metropolitan Life Insurance in 1910. He didn’t stay for long. Metropolitan moved him to Muncie, Indiana, by 1912.

Lynch’s place was quickly filled by George Boren, a young traveling salesman from Arkansas who sold wholesale groceries. Like so many people who come through Hopkinsville, Boren found his home there. He stayed at the Dalton house until about 1920, when he married a woman named Blanche.

They purchased the house at 167 Alumni Ave., which became their life-long home.

The numerous women who worked as cooks and maids for the Dalton family were also members of the household, though they wouldn’t have been considered boarders. I discussed them in an earlier article. Their room and board was likely included as part of their pay, and they occupied the small room beneath the kitchen.

The Parsonage

In 1924, Monroe Dalton sold his house to First Methodist Church. It was the church’s parsonage until the early 1950s. We’ll explore this in greater detail later. But I mention it now because 1930 saw the highest number of boarders ever at 713 E. Seventh St.

With the onset of the Great Depression, the percentage of boarders in Hopkinsville did something unexpected. It dropped sharply in half. This is surprising and counter-intuitive, and I’m not sure why it happened. It certainly wasn’t true for the microcosm of the Dalton house, where the number of paying boarders was higher in 1930 than ever before.

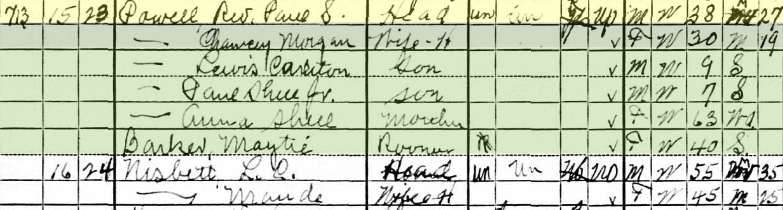

In 1930, the Rev. Paul Shell Powell and his wife and two young sons lived at 713 E. Seventh St. They were joined by three boarders; a single woman named Maytie Barker and a couple named Lilburn and Maude Nisbett. The Nisbetts almost certainly lived in the small room beneath the kitchen. This room had been the cooks’ quarters in the Dalton family’s time, but none of the ministers seem to have employed staff.

The Nisbetts

Born in Madisonville in 1868, Lilburn Nisbett came to Hopkinsville in 1924, via Evansville and Clarksville. He worked as a clerk for the L&N Railroad before becoming a stenographer and bookeeper. Nisbett held some pretty prominent positions, like secretary of the Tennessee Tobacco Growers’ Association, and he must have made a decent living. Nevertheless, he seems to have boarded for his entire life.

When the Nisbetts lived at 713 E. Seventh St., Lilburn was 62 years old Maude was 45. Throughout their marriage, Maude never worked. I couldn’t find much about her, but I hope she had some kind of social life. I can’t imagine spending all day, every day, in the small room beneath our kitchen.

Maytie Barker and Santa Anna’s silver

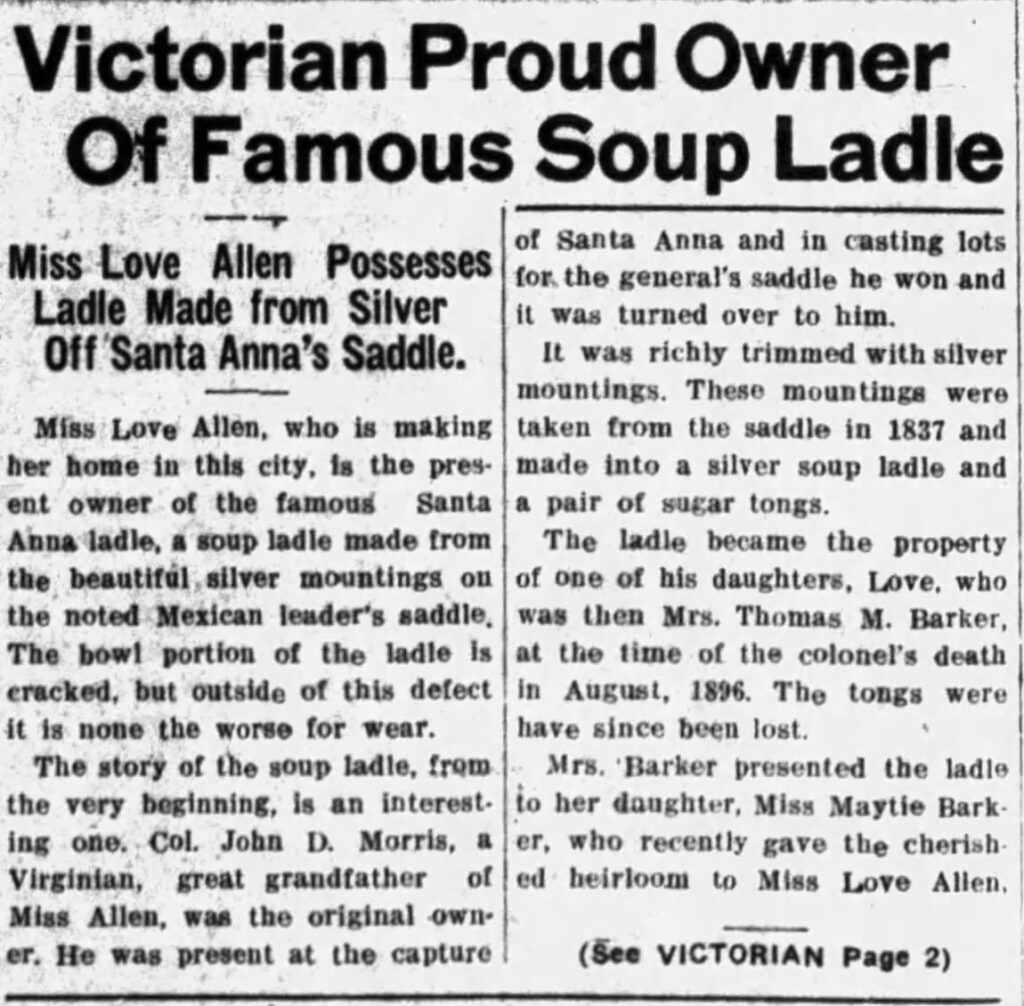

The other boarder in 1930 was Maytie Barker. She was 50, single, and worked as a public school teacher. Born Margaret Lewis Barker, Maytie came from a family with deep roots in the American frontier. For generations, her family straddled Texas and Kentucky and served their soup with a celebrated ladle supposedly made from Santa Anna’s silver.

Maytie Barker grew up on a farm in the Gordonfield area of Christian County. She was the youngest daughter of Mary Love Morris and Thomas Meriwether Barker. She was the teacher for the Gordonfield school in the first decade of the 1900s. After the death of her parents around 1920, she moved to Hopkinsville and worked at one of the city’s public schools.

Col. John Dabney Morris

Even as Maytie’s living situation changed, she carried with her the famed Santa Anna soup ladle and the memory of her family’s Texas connection. Maytie’s maternal grandfather was a Virginian named John Dabney Morris who had a knack for being present where American history unfolded.

At 21 years old, John Morris finished his training as a lawyer in Virginia and made the trek to the brand new Texas Republic. He was almost immediately elected attorney general and went on to serve in the republic’s congress in 1841-42. After this term, he inexplicably left Texas for Christian County. Here, he married Margaret Lewis Meriwether, another native Virginian, and set up a farm. By 1860, he was a wealthy, large-scale farmer who owned 88 enslaved workers.

Mexican-American War

John Dabney Morris hadn’t been in Kentucky long when Texas became a really hot topic. The United States annexed Texas in 1845 and went to war with Mexico the next year. John Morris joined up as a volunteer and once again made his way to Texas. He was supposedly present at the Mexican President Santa Anna’s capture after the Battle of Cerro Gordo, during which Santa Anna lost all of his posessions, including his cork leg and pride. The soldiers cast lots for Santa Anna’s things, and John Morris reputedly won the saddle, which was richly trimmed in silver.

In Barker family lore, the silver from this saddle was eventually cast into a soup ladle and sugar tongs, which Morris gave to his two daughters, Mary and Fanny. Mary got the soup ladle, and I’m guessing the sugar tongs belong to Fanny Morris’ descendents. Eventually, Mary passed on the ladle to her daughter Maytie, who generously gifted it in 1938 to her sister Fanny.

More about Morris

True to form, John Dabney Morris became embroiled in the next conflict in American history, the Civil War. This time, he opposed the U.S. government. When Kentucky failed to secede, secessionists held a convention in Russellville in 1861 seeking to set up a rival Confederate Kentucky government. They appointed John Dabney Morris to a key position: bank commissioner. His job was to sieze as much money in Kentucky banks as he could for the Confederacy.

Just one month before this convention, Morris’ wife Margaret died. At this point, it seems he threw caution to the wind. In 1862 he enlisted in the Confederate Army as a private — at the age of 46. He soon was the volunteer aide-de-camp for General John S. Williams. Williams and Morris were old war buddies from the Mexican-American War. In 1864, Morris was appointed colonel of Kentucky’s Provisional Army of the Confederate States of America. While recruiting, Morris was captured by the U.S. Army and exchanged as a prisoner of war, ending his role in the conflict.

John Dabney Morris quietly returned to Christian County. In 1880, he was back working as a lawyer. An aged widower, he boarded with the James Wood family on East Seventh Street. He died in 1896. His obituaries mostly talk about his role in the Texas Republic and the Mexican-American War. But I don’t think his family forgot his participation in the Civil War.

End of a way of life

Forty years later, Morris’ granddaugther Maytie Barker was a member of the United Daughters of the Confederacy. In a final demonstration of her family’s dual identity as both Texans and Kentuckians, Maytie Barker died in Victoria, Texas, in 1950 and was brought back and buried in Pembroke.

As for the soup ladle, your guess as to whether or not it was actually made from silver from Santa Anna’s saddle is as good as mine. For me, this question is periphery to the story. As with so much family oral history, it’s the story itself and the truth it tells about the family that’s precious. And the Barker family never forgot their dual citizenship or participation in American history.

Boarding as a way of life fizzled out during the mid-20th century. The percentage of boarders in Hopkinsville rebounded in 1940 to 4.6% but had begun a steady decline to 4.1% by 1950. This was likely a permanent downward trend — we’ll see what the 1960 census tells us when those details become public in 2030. Neither of the Methodist ministers who lived at the Dalton house in these years took on boarders or domestic staff. America’s seismic cultural shift of the 1950s did alway almost entirely with this mode of living.

The boarders at 713 E. Seventh St. may not have left a mark on the building, but their stories are enmeshed with the house. In a way, I think they must have become part of the family.

Grace Abernethy is a historic preservationist and artist who specializes in caring for and recreating historic architectural finishes. She earned her Master of Science in Historic Preservation from Clemson University in 2011 and has worked on historic buildings throughout the eastern United States. Abernethy was a recipient of the South Carolina Palmetto Trust for Historic Preservation Award in 2014 and won 2nd place in the Charles E. Peterson Prize for the Historic American Buildings Survey in 2011. She and her husband, Brendan, moved to Hopkinsville from Nashville in 2020. She works as an independent contractor and is a board member of the Hopkinsville History Foundation.