“No other building material offers such a low cost of maintenance as Brick. There is literally nothing to do, year after year to the outside walls of a Brick House. If you are building for home or investment, why use a material which must be constantly painted, repaired or even replaced. Why not use Brick: The Everlasting Material.”

This Dalton Bros. Brick Company advertisement ran repeatedly in the 1910s. As far as ads go, it’s fairly truthful. But historic brick does need some specialized care. Today, I’ll delve into the Dalton Bros.’ substantial legacy in Hopkinsville and discuss maintaining historic brickwork.

The Dalton Bros. Brick Company

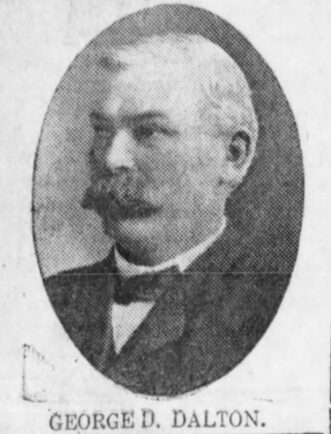

You’ve already met Thomas Monroe Dalton — now let me introduce his older brother, George. A large man with a sandy-colored walrus moustache, he was described as “kind hearted, generous and considerate.” George was the mouth, Monroe the hands of the Dalton Bros. Brick Company.

Together, they built much of the historic Hopkinsville we know today, particularly dowtown. No other business has left as visible a legacy on Hopkinsville’s built environment as the Dalton Bros. Their fingerprints are everywhere.

Monopoly

George and Monroe Dalton established the Dalton Bros. Brick Company in Hopkinsville in 1882. They were transplants from Robertson County, Tennessee, and came from a family of brick masons. George and Monroe trained as masons but took their careers to the next level: manufacturing. They produced brick and employed masons to build with it.

Their timing was on point; a fire devastated downtown Hopkinsville the same year they arrived.

George was the president of the Dalton Bros., and managed building projects. Monroe oversaw brick production. According to the Hopkinsville Kentuckian newspaper, the ingredient that made Dalton brick superior to others was the clay that the company used. The process of moulding and firing the brick was the same as in other factories of the time. You may think me biased, but I think there may be something to this! The 2022 New Year’s Day tornado dealt the Monroe Dalton house a direct hit, tumbling the chimney. Most of those bricks survived intact.

By the 1900s, the entire Dalton family, including some aunts and uncles, had relocated to Hopkinsville. Many were involved in the brick company. Uncle T.R. Mason worked as their bookkeeper in the 1900s. Younger brother Hilliard was a partner around the same time; his tenure terminated with his tragic and untimely death in 1906. Another younger brother, Garner, joined in the 1910s. But the mainstays of the business were always George and Monroe Dalton.

The Kentuckian declared in 1901 that the brothers had a virtual monopoly on the brick business in Hopkinsville but had scrupulously continued to charge fair rates. In 1911, the Dalton Bros. incorporated. By that time, the company employed over 100 men.

Brick basics

The Daltons may have been fluent in brick, but historic homeowners today often find caring for it baffling and daunting. Knowing some basics and a few ground rules can help dissipate this intimidation.

Bricks are fired clay. Through the antebellum period, they were often made by hand. By the time the Dalton Bros. came about, however, machines pressed the clay into molds. This process produced pressed brick — stronger than the hand-moulded blocks, but still much softer than its modern counterpart.

Once moulded, bricks dried for several weeks before being fired at a high heat in a kiln, giving them their permanence. Otherwise, they would just be dried mud.

Firing brick creates a protective external skin that allows it to “breathe” by releasing moisture. If a brick cannot shed moisture, it will eventually turn soft and crumble. This is why sandblasting and painting historic brick are both discouraged. Sandblasting removes this skin, subjecting a brick to moisture with no exterior protection. Painting brick blocks the pores of the skin, trapping moisture inside.

As the Dalton Bros. say, brick requires practically no maintenance.

Mortar matters

Mortar, however, is a different story. Historic mortar is sacrificial. It is meant to be replaced. Historic mortar is made of two primary components: slaked lime and sand. Mixing the dry mortar mix with water sets off a chemical reaction in the lime. As the water evaporates, the lime cures, or hardens, binding the sand together. By the time the Dalton house was constructed, masons often added small amounts of Portland cement to the mix to speed up curing time.

Historic mortar must be softer than the bricks it ties together. When a brick wall settles, the mortar compresses and absorbs the movement, protecting the bricks from cracking. A side effect of its soft nature is that mortar breaks down and washes away over time. When this happens, the crumbling mortar should be scraped out and replaced. This is called repointing.

Mortar used for repointing should be similar in composition to the existing historic mortar. This new mix will be lime-based and include a lot of sand and very little Portland cement. Pre-made mixes from the hardware store are primarily Portland cement, with very little sand and lime, and will be too hard for historic bricks, eventually cracking them.

To learn more about historic mortar and masonry, check out the National Park Service’s preservation brief.

Case study: Monroe Dalton House

Our house needs quite a bit of repointing, so I did a mortar analysis shortly after we bought it. The Dalton house has two main types of mortar, one red and one sandy-colored. The red mortar is on the front and sides of the house. The sandy-colored mortar is used on the back of the house and the limestone foundation.

I ran samples of both through acid digestion, a process that dissolves the lime in the mortar. This allows you to calculate the proportion of lime to sand in a sample. The results showed the sandy-colored mortar to be one part lime to four and a half parts sand. The red-tinted mortar had a much higher lime content; it was one part lime to two parts sand. These two mortar mixes will guide future masonry work we do on the house.

Interestingly, the tinting additive for the red mortar is crushed brick, which the Daltons doubtless had in abundance. They used this same aesthetic of matching the mortar to the brick color on other red brick buildings around town from this period. You can see it on the Dalton Bros. building on Seventh and Virginia streets.

Dalton brothers’ legacy

In 1914, the Kentuckian noted that, “With but few exceptions, the Daltons have built the business blocks of Hopkinsville as they are to-day.”

Today, some of these buildings are gone. But many are still here.

The Dalton Bros.’ impressive resume includes the Hotel Latham, the Carnegie Library, the Dalton Bros. Building at Seventh and Virginia streets, the freight depot on East Ninth Street, several wings of Western State Hospital, the Elks Home, the old high school on Walnut Street and other public school buildings, and the Princess Theater. And these are just the public and downtown buildings they built before 1920! There were also residences, infrastructure and later buildings.

The Dalton Bros. Brick Co. endured long after its founders. George died in 1922, and Monroe continued to run the company. He passed it on to his younger daughter and her husband, Sarah and Buford Todd, in the late 1930s. It then passed down their family line. In 1992, the Dalton Bros. were still running an advertisement very much along the lines of the one that started this article.

Next time you take a walk around downtown Hopkinsville, think about George and Monroe Dalton. Their lifework was creating a beautiful and, if not everlasting, lasting Hopkinsville. Now it’s our turn to take care of it.

Grace Abernethy is a historic preservationist and artist who specializes in caring for and recreating historic architectural finishes. She earned her Master of Science in Historic Preservation from Clemson University in 2011 and has worked on historic buildings throughout the eastern United States. Abernethy was a recipient of the South Carolina Palmetto Trust for Historic Preservation Award in 2014 and won 2nd place in the Charles E. Peterson Prize for the Historic American Buildings Survey in 2011. She and her husband, Brendan, moved to Hopkinsville from Nashville in 2020. She works as an independent contractor and is a board member of the Hopkinsville History Foundation.