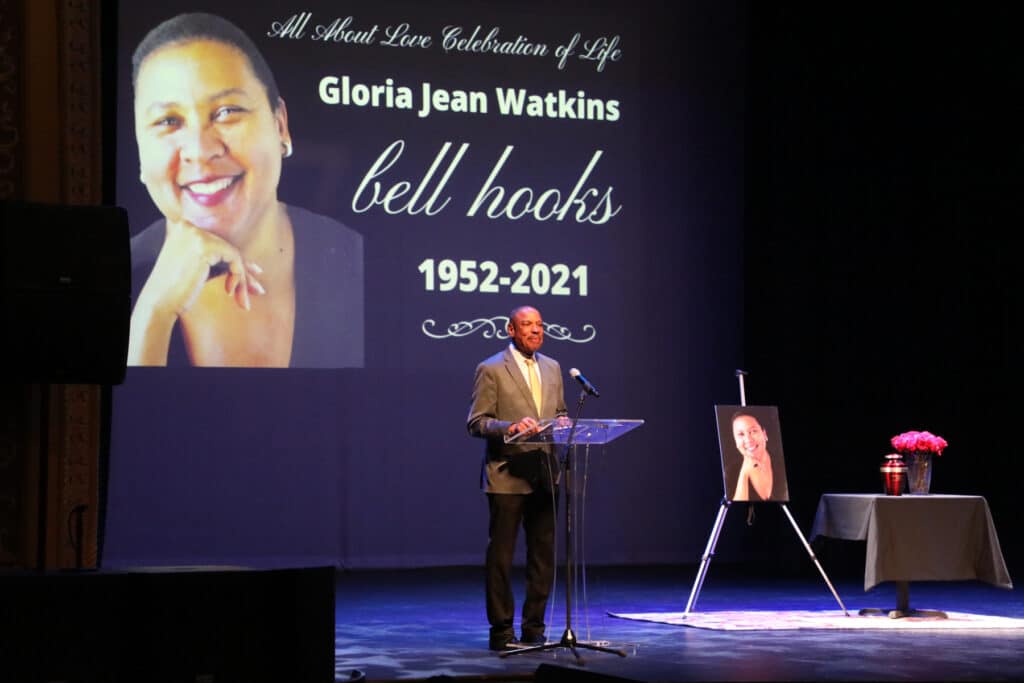

People came from across town, from other parts of Kentucky and from as far away as New York to pay their respects Saturday to the feminist author and activist bell hooks, who was born Gloria Jean Watkins to a working-class Hopkinsville family on Sept. 25, 1952.

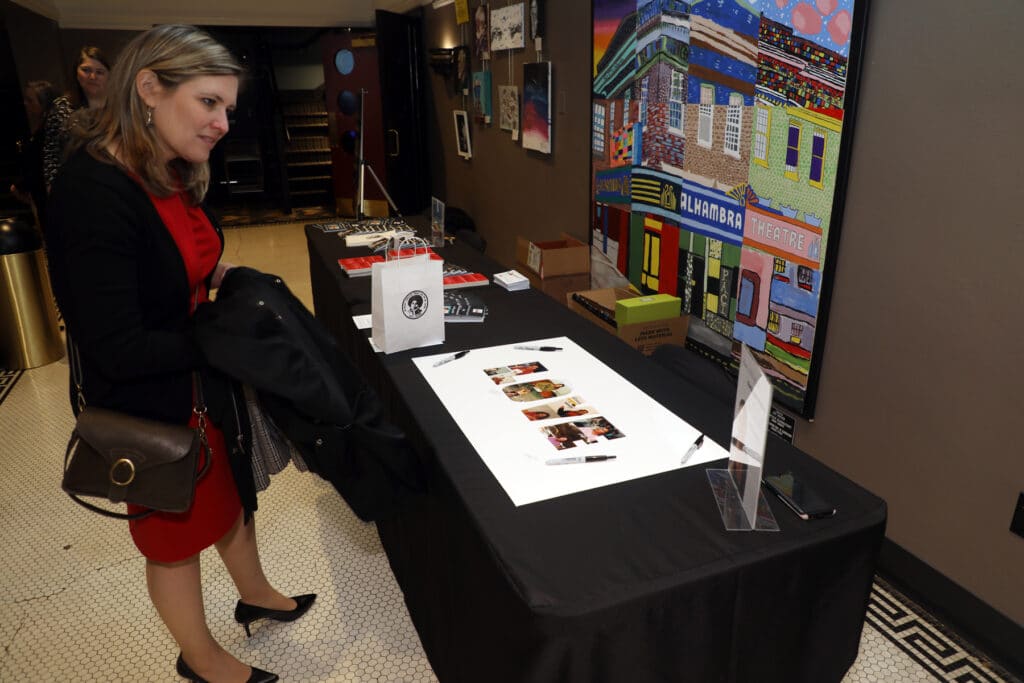

They sat shoulder to shoulder in the Alhambra Theatre, a crowd of about 400 — childhood friends, literary luminaries, relatives, historians, high school classmates, civil rights activists, hometown admirers, clergy and scholars. Each one was a testament to the profound impact of hooks, the author of more than 30 books, who died Dec. 15 of renal failure at her home in Berea. She was 69.

The greatest weapon

Crystal Wilkinson, who is Kentucky’s Poet Laureate, recalled meeting hooks for the first time at a writing conference in 1993.

Until then, Wilkinson had never heard such a powerful reflection of her own identity as a Black woman from Kentucky.

“We were listening to bell that day the way that my family used to listen to country preachers back down home,” said Wilkinson, who grew up in Casey County. “Bell had this way of turning the concepts and ideology of feminism into brilliant common sense. We sat mesmerized. We were all empowered. I think we all came out of that room with our back straighter and we were ready to go out into the world to make a change.”

After hooks returned to Kentucky permanently and began teaching at Berea College, she and Wilkinson reconnected and became friends. She said hooks taught her that anything was possible for “rebellious, bookish Black girls.”

“She also operated, as many have already said, with the idea that love was the most powerful tool that we have to combat all forms of systemic oppression. Love, bell taught us, was indeed the greatest weapon,” she said.

The concept was central to the month-long celebration in Hopkinsville of hooks. Her sister, Gwenda Motley, led a committee that organized the effort with an emphasis on her 2000 book “All About Love: New Visions.”

A little girl who changed the world

During the service at the Alhambra, speakers described hooks in many ways. She was brave, intelligent, blunt, magnificent, contrary, loving, stubborn, mischievous, passionate, radical and complex, they said. She loved dance parties, a good steak, vegetables from a friend’s garden, art, movies and stories told around a dinner table. She helped young writers without ever telling them what she had done. She spoke to children with as much regard as she gave celebrities. She read and wrote every single day.

“She was incredibly blunt,” said novelist Silas House, who was hooks’ friend for several years. “But the longer I knew her, the more I began to see it as direct honesty, and I respected that — deeply.”

She always sat at the head of his dinner table and could tell stories all night. She often wept.

Once he went to a country café with hooks. He had to wait while she went to every table and spoke to each diner. She shook hands. She patted their shoulders. She talked to them about cars and how much she liked to shop at Goodwill stores.

“When we sat down, I said, ‘Well, I swear you know everybody in here,’” House recalled. “She said, ‘I don’t know a single one of them … I wanted every one of them to have to speak to a Black woman today.’”

House remembered how hooks often referred to herself as “a little country girl from the hills.”

“She was proud of that, even though aspects of it held pain for her,” he said. “And she talked about both the joy and the pain. She was troubled by Kentucky, but she also loved it fiercely. Most of all I keep thinking of that little girl — about the burst of all of that intelligence and fierceness and bravery, as she played in the hills of Christian County, Kentucky, or sat against the tree and read, or wrote in her notebooks. I keep seeing that little girl and think about the way she changed the world.”

Lifted up in love

When her parents were still living and hooks came home to visit, childhood friend Wendell Lynch was always invited to stop by and see her. It was like a family reunion and a block party. The Watkins house on Hayes Street was filled with the aroma of fried chicken and hot water cornbread, he said.

“Everyone would be there,” said Lynch, who is now mayor of Hopkinsville and served as master of ceremonies for the celebration of life.

“She would really feel that she has been lifted up in love today,” he said of the gathering at the Alhambra.

A country connection

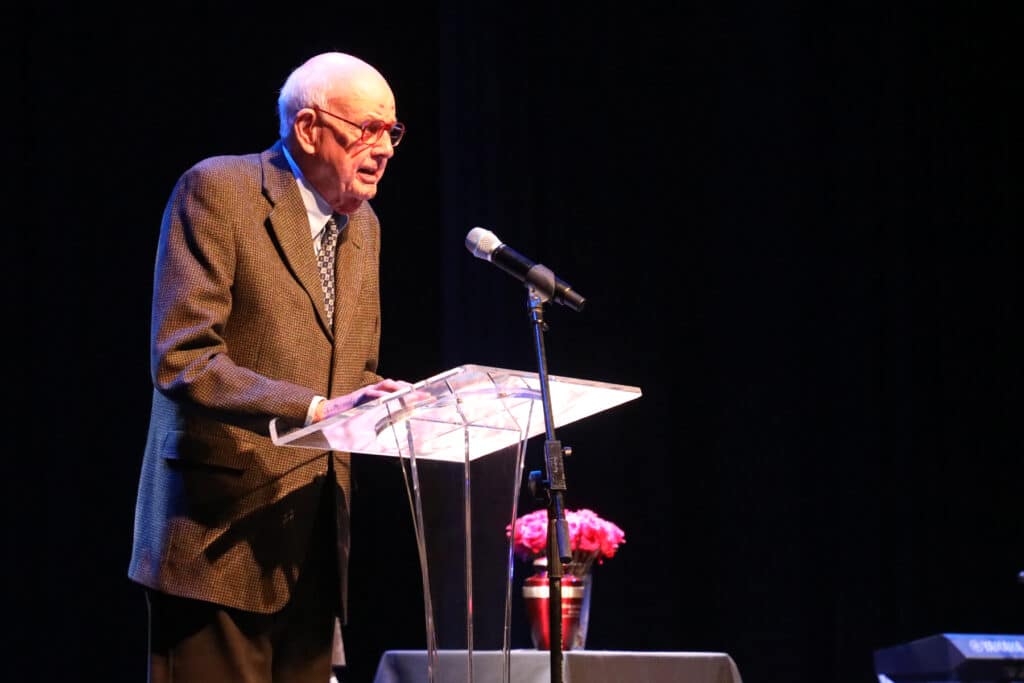

Wendell Berry, who like hooks is a member of the Kentucky Writers Hall of Fame, shared an important connection with her through their country upbringings.

“A good many years ago, when I heard that bell hooks was speaking favorably of me and some of my work, I thought that was remarkable. It seemed remarkable, of course, because the racial division is so prominent and so much in the way. And then I met bell hooks. We sat down and talked …,” he said.

As a member of the disappearing class of agrarians, Berry said he reads bell hooks with a sense of not only being spoken to but also of being spoken for.

School days

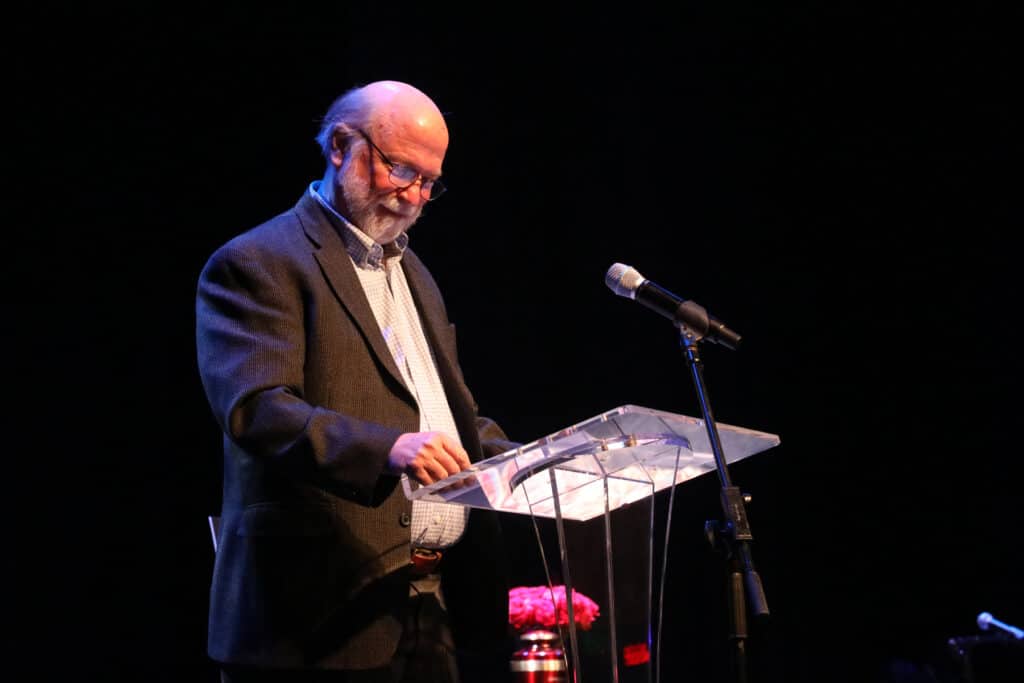

Two white classmates from Hopkinsville High School — Ann Petrie and Ken Cooley — shared their memories of Gloria Watkins and of the period of local school integration.

“It should have been apparent to anyone who was paying attention back then that Gloria was a special soul,” said Petrie.

“What I miss most when someone is gone is the sound of their voice, that I’ll never hear it again. But Gloria’s voice lives on through her writing, so I can still hear, and for that I am thankful and eternally grateful. I only hope that those to come behind us will also hear and be challenged by it,” she said.

Cooley had moved into Hopkinsville at the start of his sophomore year, the same year that Gloria had to leave Attucks High School, the county’s segregated Black school. He recalled that Black students, who rode buses that arrived early, were forced to sit in the gym until classes started every day while white students were allowed to freely stroll through the hallways.

“There had to have been a better way to solve the failures of desegregation than forcing the victims to solve the problem and bear the burden themselves,” said Cooley.

Years later, he read hooks’ description of that time and how hard it was for the Black students.

“Gloria would not appreciate me sugar-coating the lifetime of emotional scars this left on her and many of those involved,” he said to introduce a passage from “Yearning: Race, Gender, and Cultural Politics,” which hooks wrote in 1990. She wrote:

“I sat in classes in the integrated white high school where there was mostly contempt for us, a long tradition of hatred, and I wept. I wept throughout my high school years. I wept and longed for what we had lost and wondered why the grown black folks had acted as though they did not know we would be surrendering so much for so little, that we would be leaving behind a history.”

Moments later, the Alhambra audience laughed and clapped loudly when Cooley shared an example of teenage Gloria’s sense of humor. He read her inscription in his 11th grade yearbook:

“Ken, I don’t know whether I should write all the things I hate about you or the few, little things that I like about you. It’s been OK this year but I’m hoping next year will be better. Stay cool and maybe next year I won’t hate you so much. From one ardent racist to another. Love Gloria.”

Cooley said, “This was, of course, pure Gloria.”

It was a privilege to know Gloria and to learn from her, he said.

“Gloria, dear, I know you are listening,” he said. “Thank you for teaching us. It is, indeed, all about love.”

Leaving a legacy

Several people sent videotaped messages for the service, including Gov. Andy Beshear, who said, “She pushed us forward. She encouraged us to be more inclusive in our thoughts and actions, and she tackled some of the most important issues by bringing new light and awareness to things most often overlooked.”

Three community groups announced plans to keep hooks’ legacy alive in Hopkinsville.

Holly Boggess, executive director of the Downtown Renaissance District, said a bell hooks mural will be painted on the Christian County Historical Society building on East Ninth Street. Yvette Eastham spoke about plans to erect a statue in hooks’ honor for the Round Table Literary Park at Hopkinsville Community College. Francene Gilmer described an ongoing commitment to hooks’ influence at the Christian County Literacy Council. Earlier in the week, the council presented awards to winners in the bell hooks Memorial Writing Contest.

Motley concluded the service for her sister with this message:

“Gloria began writing this book, ‘All About Love: New Visions,’ because she felt that across the United States people were moving away from love. So I know our Gloria Jean, and the world’s bell hooks, would be thrilled to know that Hopkinsville has not forgotten her — nor have we forgotten how to love and how to show it. So on behalf on the family of Gloria Jean Watkins, thank you to all of you for being all about love today.”

- RELATED: See more coverage of bell hooks

- RELATED: ‘To me, she’s Gloria Jean’

(Editor’s note: Jennifer P. Brown served on the committee that helped Gwenda Motley plan the celebration of life for bell hooks. Motley is a Hoptown Chronicle board member.)

Jennifer P. Brown is co-founder, publisher and editor of Hoptown Chronicle. You can reach her at editor@hoptownchronicle.org. Brown was a reporter and editor at the Kentucky New Era, where she worked for 30 years. She is a co-chair of the national advisory board to the Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues, governing board past president for the Kentucky Historical Society, and co-founder of the Kentucky Open Government Coalition. She serves on the Hopkinsville History Foundation's board.