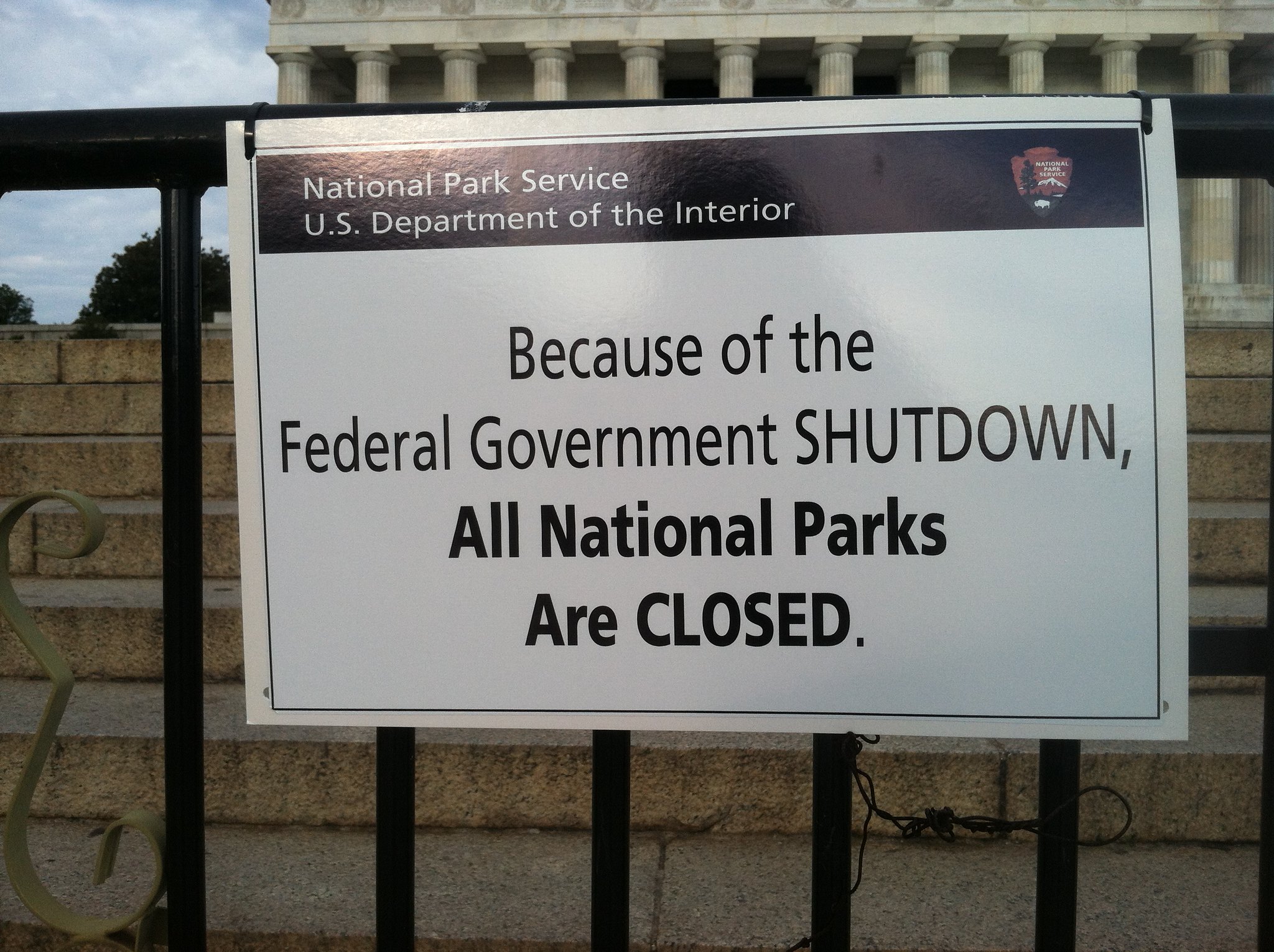

The U.S. is moving toward a government shutdown. House and Senate appropriators are divided on spending levels, policy riders and additional items, such as support for Ukraine.

As a political scientist who studies the evolving budget process, as well as brinksmanship in Congress, it is clear to me that this episode prompts many important questions for how the U.S. is governed.

There’s the larger, long-term question: What are the costs of congressional dysfunction?

But the more immediate concern for people of the country is how a shutdown will affect them. Whether delayed business loans, slower mortgage applications, curtailed food assistance or postponed food inspections, the effects could be substantial.

- RELATED: McConnell: Government shutdowns create unnecessary hardships for millions

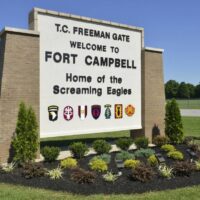

- RELATED: Active-duty military would work without pay in shutdown, White House warns

Affected: Farm loans to Head Start grants

The total federal budget is almost US$6 trillion. A little over one-fourth is discretionary spending that is funded by the annual appropriations process and thus debated in Congress. This portion of spending provides money for virtually every federal agency, roughly half of which goes to defense. The rest of yearly federal spending is on mandatory entitlement programs, mainly Social Security and Medicare, as well as interest on the national debt.

The Office of Management and Budget, which oversees both development of federal budget plans by federal agencies and their performance, regularly requires agencies to develop shutdown plans. Because agencies continually update these plans, no two shutdowns are exactly alike. Details depend on the agency, program and duration of the shutdown, as well as laws passed with funding since the previous shutdown, and the administration’s priorities. These plans identify a variety of ways the shutdown will affect Americans.

If a shutdown happens this year, new loan approvals from the Small Business Administration will stop. The Federal Housing Administration will experience delays in processing home mortgage loans and approvals. The Department of Agriculture will not offer new farm loans. Head Start grants will not be awarded, initially affecting 10,000 young children from low-income families who are in the program.

Some food inspections by the Food and Drug Administration, workplace safety inspections by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, and environmental safety inspections by the Environmental Protection Agency could be delayed, as they have been when the government stopped functioning in the past.

During the last shutdown, about 60,000 immigration hearings, organized by the Department of Justice and not the courts, were canceled and had to be rescheduled. This year would also see cases involving noncitizens who are not being held by the government reset for a later date, even as other immigration services proceed.

Infrastructure projects awaiting approval from the Environmental Protection Agency could be stalled. The National Institute of Health’s clinical trials for diseases could also be slowed.

This is not a comprehensive list. Agency plans show what happens when federal workers are furloughed – that is, those who cannot report to work in a shutdown. Furloughs will apply to over 700,000 out of roughly 3.5 million federal employees, but even more workers will be “excepted” and required to work without pay until the shutdown ends.

That of course means employee hardship. But like past shutdowns, unpaid workers can fail to report to work in larger numbers. Americans relying on those services will face delays. There may be air travel delays as well, as air traffic controllers and Transportation Security Administration agents go without pay.

Not affected: The IRS, postal service and entitlement programs

Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid benefits are entitlement programs that are not included in the annual appropriations process. Americans relying on these programs will not see those benefits affected. But these programs require administration. Federal employees would not be available to verify benefits or send out new cards.

There are additional funding sources for government activities, beyond entitlement programs, that aren’t included in the annual appropriations bills and thus are unlikely to be affected by a shutdown.

The U.S. Postal Service, independently funded through its own services, will be unaffected by a shutdown. The federal judiciary could operate for a limited time, funded by court filings, fees and appropriations allocated off the yearly cycle. But this funding won’t last long – 10 days was an estimate for the 2013 shutdown. The Supreme Court, which has functioned in previous shutdowns, is expected to continue its typical schedule.

Sometimes, agencies have funding that exceeds the typical annual appropriations cycle. Or, earlier laws may have been passed that fund activities of an agency in whole or in part. The Inflation Reduction Act provided funds to run the IRS through 2031. Previous shutdowns saw significant IRS furloughs and employees walking off the job. This year, the IRS promises to be fully operational despite a shutdown.

A variety of advance appropriations also exist that provide funding for various programs one year or more beyond the year the appropriations bill was passed, including Veterans Affairs medical care; most VA benefits are unaffected.

The primary law governing funding gaps also makes exceptions for “emergencies involving the safety of human life or the protection of property,” which includes a variety of military activities.

The big question mark

The major unknown is, of course, how long a shutdown might last. Food assistance programs – including the federal food program for poorer women, infants and children, called WIC, and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP – which have some contingency funds that carry over into the next fiscal year but are running low, run the risk of those accounts running out.

The federal judiciary has limited funds. There are also a variety of federal grants to states and localities that could be short on funds, such as disaster relief and economic development programs, in addition to nutrition assistance. Government officials at the federal, state and local levels will have to make choices about whether a federal shortfall should be covered by state funds, or if workers should be furloughed. Some of these funds have been protected by increased funding in recent laws: The Highway Trust Fund is solvent through 2027, due to the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law of 2021.

The economy as a whole will suffer more the longer a shutdown continues. The Congressional Budget Office estimated that the last shutdown, in 2018-2019, reduced gross domestic product growth by 0.2% in the first quarter of 2019. While that 35-day partial shutdown was the longest in U.S. history, it did not affect all agencies.

Federal employees and contractors are disproportionately hurt. Federal employees who are furloughed or excepted and do not receive pay during the shutdown will receive it retroactively, according to a 2019 law passed as a response to the last shutdown.

No such policy exists for contractors working for the federal government, including services ranging from janitorial to manufacturing. Beyond affecting individual workers, the private sector loses business and adjusts its hiring decisions and other practices.

Laura Blessing, Senior Fellow, Government Affairs Institute at Georgetown University, Georgetown University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Laura Blessing, Ph.D. is a Senior Fellow at the Government Affairs Institute (GAI) at Georgetown University and also teaches in the McCourt School of Public Policy. Prior to coming to GAI, she earned her PhD from the University of Virginia, where she was also a Miller Center National Fellow and a fellow for the Bankard Fund for Political Economy. Her interests include institutions, political parties, and policy, particularly tax and budget. She has worked on the Hill as an American Political Science Association (APSA) Congressional Fellow, serving as the legislative assistant for tax policy for a senior member of the Ways and Means Committee. She has published on the eroding budget process, tax policy in the 2016 Presidential campaign, social movements and the Presidency, and the importance of practical experience in politics informing scholarship. She has engaged in congressional testimony and other public commentary on politics in various media venues, including NPR’s Marketplace, CSPAN, and other politics outlets. She is currently working on a book on the politics of tax policy from the midcentury period to today.