About five billion years ago, stars merged and exploded, creating uranium that eventually became embedded in the Earth. As uranium decays as part of a natural process, it emits radon, a radioactive gas. This gas can seep into homes and other buildings through pipes and cracks in foundations. If present in high enough concentrations, the gas and its byproducts can damage lung tissue and cause lung cancer.

This guide will explore:

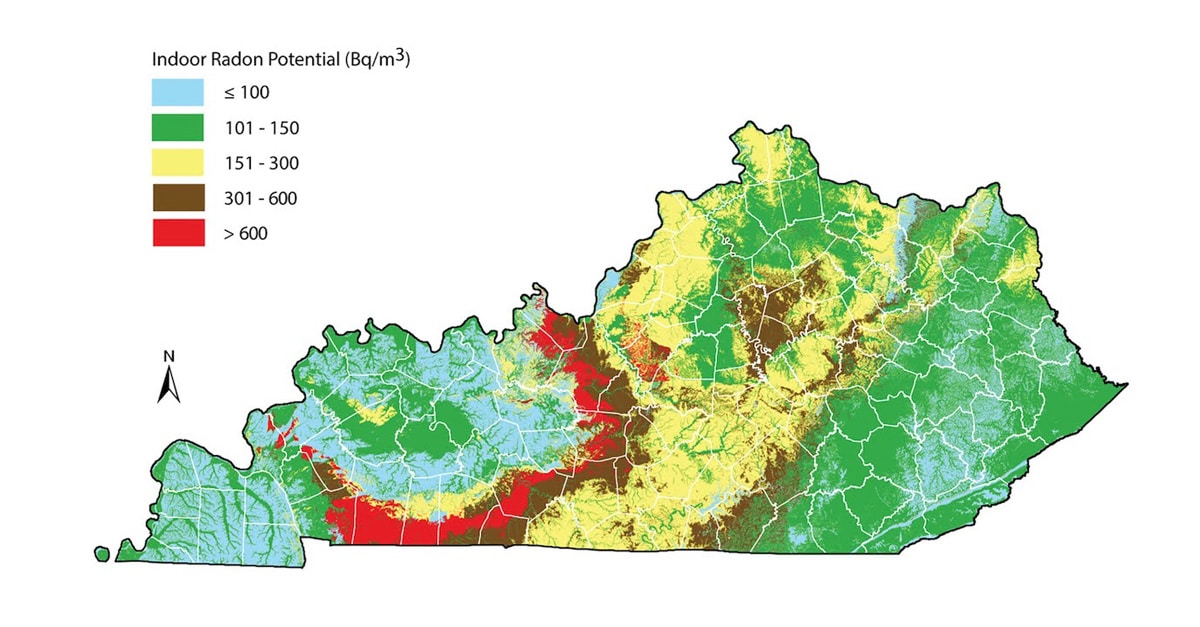

Radon is prevalent across the country, but particularly in areas with large uranium deposits. The Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Geological Survey identified areas where it is a greater concern. (See if you live in one of these areas by checking your state map.)

Local Risk

A recent study by the University of Kentucky revealed that individuals living in the southern half of Christian County have a high indoor radon potential. Read more here.

We learned about radon risks while reporting on the lingering health threats from the three-decade uranium mining boom in the United States that peaked during the Cold War. It quickly became apparent that many people are unaware of risks from radon and struggle to find accurate information on the radioactive gas.

Take Jackie Langford. When she moved into a home near a former uranium processing site, no one alerted her to the dangers of radon. Many of her neighbors had also been surprised to learn of the risks. That’s partly because there are no federal laws requiring developers and property owners to disclose information about the presence of the cancer-causing gas, regularly test for radon or construct buildings in ways that prevent the gas from seeping into homes.

Langford took steps to protect herself that others can take, too. To understand these steps, we spoke with state radon officials, environmental scientists and health specialists, as well as residents who live with varying radon levels in their homes. We also dug into global health reports and federal data.

Why is radon a public health threat?

Breathing in radon can be dangerous. Its radioactive particles decay in the lungs, releasing small bursts of radiation. Research shows this can damage lung tissue and cause lung cancer.

In the U.S., exposure to indoor radon accounts for 7,000 to 21,000 lung cancer deaths each year, according to estimates by the EPA. Only cigarettes cause more annual lung cancer deaths.

In Utah, which recently passed a law to assess prevention opportunities, researchers estimated the state had 5,826 radon-related lung cancer fatalities over a 50-year span — or more than 100 deaths each year.

How do I know if I’m at risk from radon?

The most effective way to learn the risk is to test for the gas (more on that below). You may also be entitled to information from the property’s current or previous owners.

In 36 states, property owners have a legal obligation to disclose radon testing results or sources of radon emissions to homebuyers. The situation is murkier for renters: Only four states require landlords to disclose past radon levels to tenants, according to a database assembled by Temple University’s Center for Public Health Law Research.

You can learn about your state’s radon laws by contacting your state radon office.

What is radon testing?

You can measure radon levels indoors using small devices and test kits, similar to smoke detectors. There are two main approaches: long-term and short-term.

Since indoor radon levels are tied to airflow, levels can fluctuate day to day and by season. This makes long-term testing, which takes between 90 and 365 days, the most accurate method. If you are interested in long-term testing, you can check out this list of long-term and continuous radon devices approved by the National Radon Proficiency Program. Your state radon office should also have information and equipment for long-term testing.

Short-term tests are a sound alternative, especially if you need results quickly. These tests take anywhere between two and 90 days. Here are best practices for short-term tests:

- Two tests are better than one. Experts recommend using two short-term tests before deciding whether to install a radon reduction system. Possible approaches are:

- Two tests, back-to-back. Put up one test and then, when it’s time to send it to the lab, put up a second test in the same spot. Make sure you are using the same test model. Average the two results to get a better sense of the radon levels in the home or building.

- Two tests, side-by-side at the same time. You can put up two test kits (again, make sure they are the same model) four inches apart. This method helps determine the accuracy of the tests and is often used in real estate transactions since it takes the least amount of time.

- Radon experts told us they consistently use tests from Air Chek and Alpha Energy Laboratories and find they’re easy to use and accurate. Experts said to avoid tests that are not calibrated since these are far less accurate. Follow the instructions on the test kit as closely as possible.

Each state has a radon program and many offer free radon testing kits. You can find the contact information for your state radon office here. Your state radon expert should also be able to answer any questions you have. The National Radon Program Services at Kansas State University has partnered with the EPA to offer discounted short-term radon test kits.

How can I get a radon test?

Each state has a radon program, and many offer free radon testing kits. You can find the contact information for your state radon office here. Your state radon expert should also be able to answer questions about setting up a test.

You can also visit the website of the National Radon Program Services at Kansas State University, which has partnered with the EPA to offer discounted short-term radon test kits.

How much radon is considered unsafe?

The more radon someone breathes in over their lifetime, the more likely they are to develop lung cancer, according to the EPA. Radon amounts are determined by calculating the rate of radioactive decay in the air, measured in picocuries per liter of air (abbreviated pCi/L).

Eleanor Divver, a radon coordinator with the Utah Department of Environmental Quality, likens the cumulative risk of radon to the risk of smoking cigarettes. If a house has an average of 4 pCi/L of radon, breathing that air every day would be the equivalent of smoking between six and eight cigarettes daily, she said.

The EPA estimates that if 1,000 people who do not smoke are exposed to 4 pCi/L of radon over a lifetime of 70 years, about seven could develop lung cancer as a result. Children are generally more vulnerable because they breathe more frequently and are closer to the ground, where radon concentrations are higher. The risk also increases for smokers — at the 4 pCi/L radon level, about 62 additional people out of 1,000 could develop lung cancer. These estimates exceed the EPA’s threshold for acceptable cancer risk.

The federal agency recommends households with an average of 4 pci/L of radon install mitigation systems to reduce radon levels.

The World Health Organization suggests mitigation systems starting at 2.7 pCi/L of radon in the air. WHO’s recommendations are based on a review of research by 100 scientists from 30 countries.

How do I get rid of radon?

The strategy for lowering radon levels depends on how the radon is getting into the house and why the gas is becoming trapped there.

To find the strategy that’s best for your residence, speak with a certified radon specialist. Here are some ways to find one:

- The National Radon Proficiency Program has a searchable database of certified radon mitigators.

- The National Radon Safety Board has its own searchable database of certified radon mitigators.

- Ask your state radon office for recommendations for certified radon mitigators.

The cost to reduce radon levels often exceeds $1,500, according to experts. Few states assist with the cost. Your state radon office might have suggestions if you need to remediate your home but need financial assistance.

Where can I get more information on radon?

The EPA publishes a Citizen’s Guide to Radon and a website with information and resources.

How do I share tips, questions and experiences with reporters?

We want to hear from you if you have had experience with radon, and are especially interested in connecting if:

- You have done radon testing and want to report the results.

- You are concerned about the indoor radon levels in your space and want to test.

- You have worked with a government agency, nonprofit or private company dedicated to radon and have insights or experiences to share.

To get in touch, email maya.miller@propublica.org. We look forward to learning from you.