Tucked away in the depths of the museum’s basement stands a wire frame apparatus bearing a metal sign.

It stands just over 4 feet tall and is 2 feet wide. Thin metal partitions divide the lower part of the larger structure. A yellow metal sign – with clear indications of weathering and even a bullet hole – hangs from the top bar. In large black letters, the sign says “Western Union” with “It’s Wise to Wire” underneath. The museum is currently using it for its intended purpose.

This artifact is a Western Union bicycle rack.

A couple of months ago, I asked Hoptown Chronicle editor Jennifer P. Brown to pick an artifact for me to feature in a column, and she chose this bike rack. I knew she was drawn to it. She featured it in a calendar of her local photography a couple of years ago. And I was glad that she chose it because this one would not have made my list.

A communications revolution

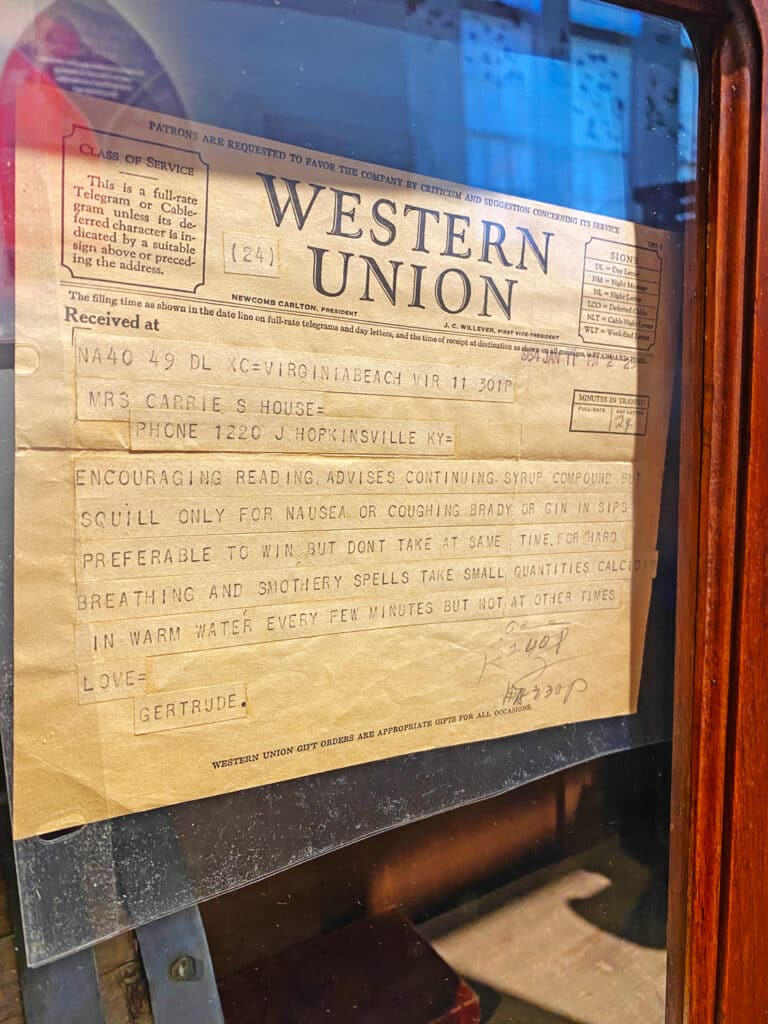

But its story has very little to do with the rack itself. It is all about communication and how the invention of the telegraph connected people across great distances. It revolutionized how people sent and received information, and it made that process so much faster and more efficient. Telegrams – in their short, choppy phrases – sent news of celebration and tragedy.

William Turner shared that Hopkinsville learned of the end of World War I by telegram. A high school boy was sleeping in the telegraph office when the message came in. He hightailed it to the fire station to tell the firefighters to ring the bell to alert the city of the good news.

When Night Riders invaded the city in 1907, one of their main targets was the Cumberland Telephone & Telegraph Office. They knew the importance of communication – and of silencing it. It was reported that the telegraph operators – all young women – were held by the masked raiders until they fled. One woman even testified at Dr. Amoss’s trial.

History of the telegram

Telegrams were serious business.

I had a lot to learn about telegraphy. According to Webster’s most basic definition, a telegraph is simply “an apparatus for communication at a distance by coded signals.”

The earliest uses of visual telegraphy (like smoke signals) have been eclipsed by the electric telegraph. The electric telegraph sends an electric current through a wire. That current then gets broken into a particular pattern – or code – that is put together and transmitted to a receiver on the other end of the wire. Morse Code, a code of longs and shorts (or dots and dashes) developed by Samuel B. Morse, made the telegraph possible and became its ticking language.

The first successful telegraph was sent on May 24, 1844 from Washington, D.C. to Baltimore by Morse and his business partners. The first telegraph was received in Hopkinsville in 1858.

By 1860, a man named William A. Wherry was listed in the census for Christian County as the telegraph operator. He was only about 18 years old at the time.

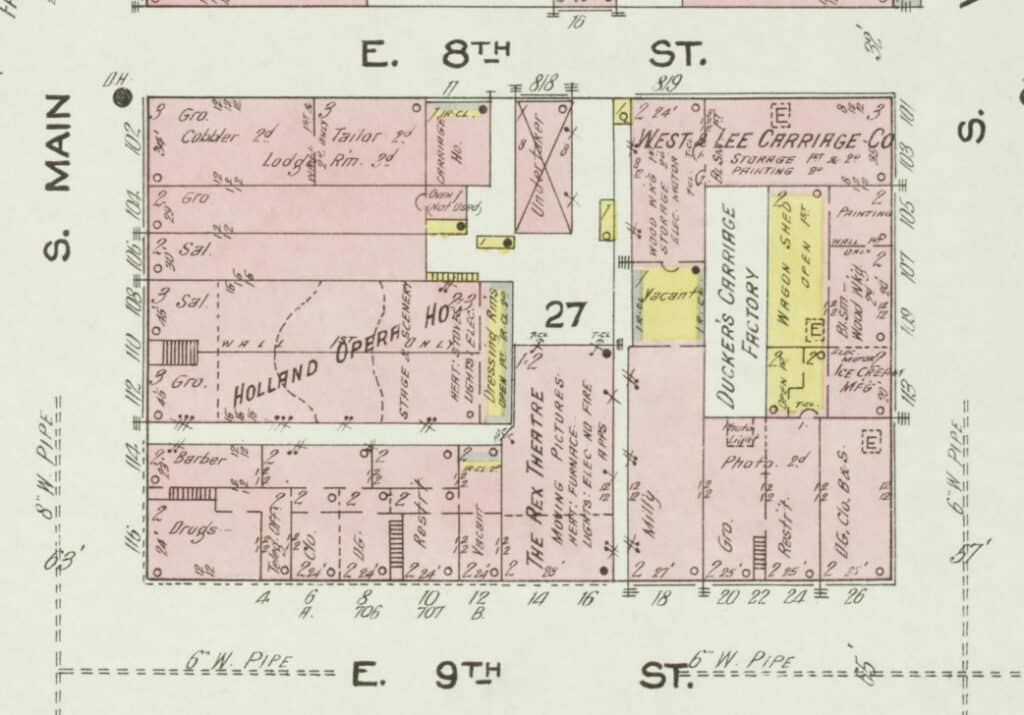

In 1873, two sisters – Martha Park Randle and Mary Park – moved here from Lavergne, Tennessee, to serve as the manager and assistant manager of the Western Union Telegraph Company. I wasn’t able to determine definitively when Western Union opened an office here, but we know it was by 1873. The office shows up on the 1886 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map on the southwest corner of Main and Sixth streets – directly across from the courthouse. The telegraph office was downstairs with offices above. The map also shows a “Tel. Off.” on the southwest corner of Main and Ninth streets, where Southern Exposure Photography is today. The 1906 Sanborn shows five different telegraph offices in downtown Hopkinsville.

Martha (known as Mattie) served as the manager and Mary as her assistant at Western Union office for 35 years and three months, according to the announcement of their retirement in the Hopkinsville Kentuckian on Nov. 26, 1908. The article speaks of Martha’s decades with the company:

“Her service has been uninterrupted for a period longer than any other business agency or enterprise in the city, without change of management. Her record is one of the most remarkable made by any operator on the Western Union system … Mrs. Randle has handled a vast volume of business, probably as many as 1,000,000 messages. She is a thoroughly efficient operator and her service at all times has been faithful, skillful and loyal to the company.”

What a glowing retirement tribute! Both Martha and Mary lived long lives in Hopkinsville. Martha passed away in 1935 at the age of 95, and Mary died in 1937 at the age of 88. Both are buried in Riverside Cemetery.

I must say something. In my head, I may have pictured telegraph operators as women. But I definitely did not picture two women running an office that served as a main source for our community’s communication to the greater world as early as 1873. That was 150 years ago! Martha Randle and Mary Park are my new heroes.

After the sisters’ long tenure with Western Union ended, the company appointed Katherine Mitchell, a telegraph operator from Bennington, Kansas. A long list of managers and operators ran the office for the next 20 years. In 1928, Newell F. Smith took the position of manager and held it until 1967. June Cardin, a longtime employee, succeeded him until Hopkinsville’s Western Union Telegraph Company office officially closed on June 24, 1972. The front page of the Kentucky New Era featured a photograph (taken by Mary D. Ferguson) of Cardin and Nell Green, the operator, as Green sent the last wire. The caption began with the headline, “Wires Are Stilled.”

That was it. I couldn’t find any more details – not an article or editorial in the days that led up to or followed.

The courier

But what about the bicycle rack? I scoured photographs in William Turner’s collection to get a glimpse of the rack on the street. I spotted it in 1957 in pictures of the major flood that inundated downtown in November of that year. Similar flood images from 1951 did not show the rack. Therefore, this Western Union bicycle rack dates from the mid-1950s. How it made it into the museum’s collection is a mystery.

The rack serves as a reminder of yet another part of the Western Union system: the courier. Couriers on bicycles delivered these short, precious messages all over town. In an article Jennifer wrote when Western Union completely ended its telegraph business in 2006, she remembers the company’s last local courier:

“In Hopkinsville, it’s nearly impossible to talk about the Western Union office without recalling the last courier for the office. Robert Guthrie, who died in 1986, carried telegrams through the streets on a bicycle.

The ring of the Western Union bell on his bicycle could signal celebration or grief. Guthrie wore thick glasses, a mental image that still sticks with many people in Hopkinsville.”

The headline for her article was clever: “End of an era. Stop.”

Jennifer has a special talent for distilling a story into words. Fewer words is way harder for me than more words. More words gives me the chance to keep going in hopes that I make it to a point eventually. The telegram didn’t allow for that. Messages were charged by the word, and according to The Telegraph in America, 1832-1920, the average length of a telegram in the U.S. in the 1900s was less than 12 words.

Phoenix Building office

In 1972, the era of telegrams ended in Hopkinsville, and in 2023, we will witness a final death knell to its memory here. Western Union Telegraph Company bounced around in different locations until 1910 when it established its office in the Phoenix Hotel. The office remained on the Ninth Street side – just past what many remember as Cassady’s Kiddie Corner – for 62 years. The Phoenix is currently slated for demolition.

It only seems fitting to give the building a final telegram farewell:

Historic Phoenix building to be razed

Oldest building on most important corner downtown

Once hotel and site of numerous businesses and offices

Longtime home of Western Union

End of an era

STOP