Eighty years ago this week, on successive days a few miles apart in eastern France, three rural Americans risked their lives to help save Europe from tyranny. One soon died of his wounds, another found fame and fortune, and the other’s heroism was almost unknown until after his death. Their lives and their valor, all recognized with the Medal of Honor, should be remembered as America reflects on its role in the world — past, present and future.

All three soldiers were in the 3rd Infantry Division, which chased German forces out of the Colmar Pocket, named for a city between the Rhine River and the Vosges Mountains. This 800-square-mile area was the last part of France held by the Germans, and had been German territory before World War I, so they fought hard to keep it.

No matter where you are reading this, you’ve probably heard of the third soldier who earned the Medal of Honor in the Colmar Pocket, on Jan. 26, 1945: Second Lt. Audie Murphy, an East Texan who was hailed as the most decorated American soldier of World War II and became a movie star.

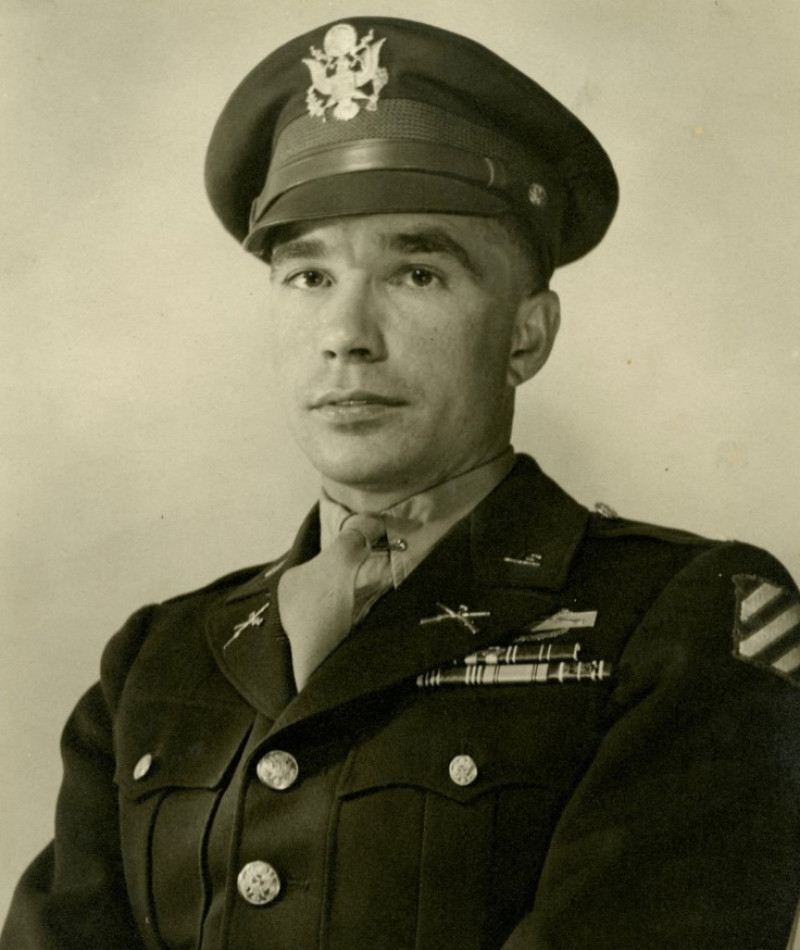

Murphy’s postwar life was in sharp contrast to that of the 3rd Division soldier who earned the Medal of Honor two days earlier, on Jan. 24. He was First Lt. Garlin Murl Conner, who didn’t get the medal until 2018, 20 years after he died, because of the fog of war — and returned to a Southern Kentucky farm that had no electricity or running water.

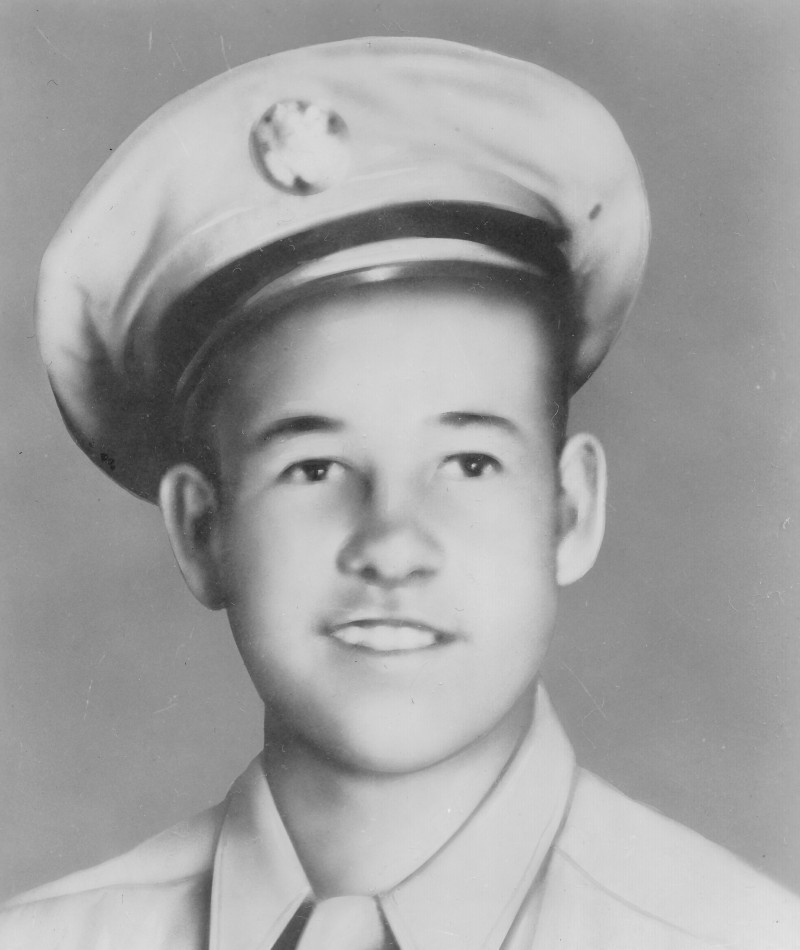

But Conner was luckier than the other Medal of Honor winner in the Colmar Pocket. On Jan. 25, 1945, PFC Jose F. Valdez of northwest New Mexico, who had already killed three heavily armed Germans in a firefight, volunteered to cover his patrol’s retreat against heavy fire. Even after he was shot through, he directed artillery fire and held off 200 Germans. He died three weeks later.

Murphy also directed artillery fire, after ordering his company to retreat. When the Germans knocked out a tank destroyer near his command post, he mounted the flaming vehicle and used its machine gun to kill or wound 50 advancing enemy troops. He suffered a leg wound, ran out of ammunition and rejoined his company, which forced the Germans back.

Conner’s heroism on Jan. 24, 1945, was also about directing artillery at great risk. He had already earned three Silver Stars and had been assigned to a staff post because he was due to be sent home after 28 months in combat and had suffered a leg wound, but when Germans advanced on the 3rd Battalion of the 7th Infantry Regiment, he volunteered to be a forward observer for artillery. He unrolled telephone wire as he ran more than 400 yards through German artillery fire and slid into a shallow ditch, from which he directed fire for three hours — finally on his own position because enemy troops were 15 feet away. The Germans finally retreated after 50 were killed and more than 100 were wounded.

Conner’s commanding officer was Col. Lloyd Ramsey, who went on to be a major general and have future Gens. Colin Powell and Norman Schwarzkopf under his command. He told his staff to seek the highest possible honor for Conner, but he was injured the next day and detailed eyewitness accounts needed for the Medal of Honor were not gathered. Instead, Conner was given the Distinguished Service Cross — after winning his fourth Silver Star.

Like most war heroes, Conner didn’t tell war stories, and his heroism was never publicly reported in Clinton County, Kentucky, where he returned to live and farm. Near the end of his life, he was visited by Richard Chilton of Genoa City, Wisconsin, a retired soldier seeking information about his uncle’s service in World War II. Conner could talk only a little, but as Chilton left, Conner’s wife Pauline showed Chilton her husband’s box of medals. When he saw the DSC and four Silver Stars, and heard the story about his heroism at Houssen, he started a campaign to get Conner the Medal of Honor — a task made daunting by federal law, Army regulations and the Pentagon bureaucracy.

The campaign got traction when Byron Crawford, then a columnist for The Courier-Journal, wrote about it and Conner’s heroism — which was news to almost all of his neighbors. One of them, Walton Haddix, took charge of the campaign and got lawyers involved. After many twists, turns and apparent dead-ends, the U.S. Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals ordered the Army to mediate the matter, and the end result was that Pauline Conner accepted the Medal of Honor from President Trump at the White House in 2018.

Pauline Conner died last year, but you can hear her story in a documentary, “From Honor to Medal: The Story of Garlin M. Conner,” produced by Jeff Hoagland with this writer as executive producer. And Murl Conner’s story is also told in an episode of “Hitler’s Last Stand,” a series produced for the National Geographic Channel.

Very little living memory remains of Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini, the fascist dictators of Europe. But such people are a feature, not a bug, of the human race. Now we must deal with other dictators and autocrats who would make the world an unfriendly place for us; will we measure up to the examples of Jose Valdez, Audie Murphy and Murl Conner?

Al Cross is professor emeritus of journalism at the University of Kentucky. He was the longest-serving political writer for the Louisville Courier Journal (1989-2004) and national president of the Society of Professional Journalists in 2001-02. He joined the Kentucky Journalism Hall of Fame in 2010. The NKyTribune is the home for his commentary which is also offered to other publications.