FRANKFORT — The League of Women Voters of Kentucky released a report Wednesday that found the General Assembly has increasingly fast-tracked bills in a manner that makes citizen participation nearly impossible — about a month before lawmakers return to Frankfort in January.

The League’s analysis found that fewer than 5% of bills that became law 25 years ago used four fast-tracked methods. In 2022, 32% of House bills passed and 24% of Senate bills passed were fast-tracked in ways that exclude the public, the report found.

The trend, which began around 2002, peaked in 2014 when fast-tracked bills increased to 42% in the House and 29% in the Senate.

- SUBSCRIBE: Sign up for our newsletters

The report, titled “How Can They Do That? Transparency and Citizen Participation in Kentucky’s Legislative Process,” reviewed seven 60-day legislative sessions between 1998 and 2022 and examined how often the General Assembly did not follow its established process to give Kentuckians time to review and comment on proposed legislation.

“Even though some legislators may claim that procedures like these have always happened, our analysis showed that 25 years ago, less than 5% of bills that became law used one or more of those maneuvers,” says a League news release. “In 2002, the percentage began to increase rather dramatically. … There is indeed a pattern of increasing use of fast-track maneuvers that make participation more difficult.”

The period studied by the League began two years before Democrats lost their narrow control of the Senate in 2000. In 2016 Republicans won control of the House. Republicans now hold supermajorities in both chambers.

Additionally, the League, which is non-partisan, made recommendations to citizens and lawmakers about how to improve transparency in the future. All state lawmakers will receive a copy of the report.

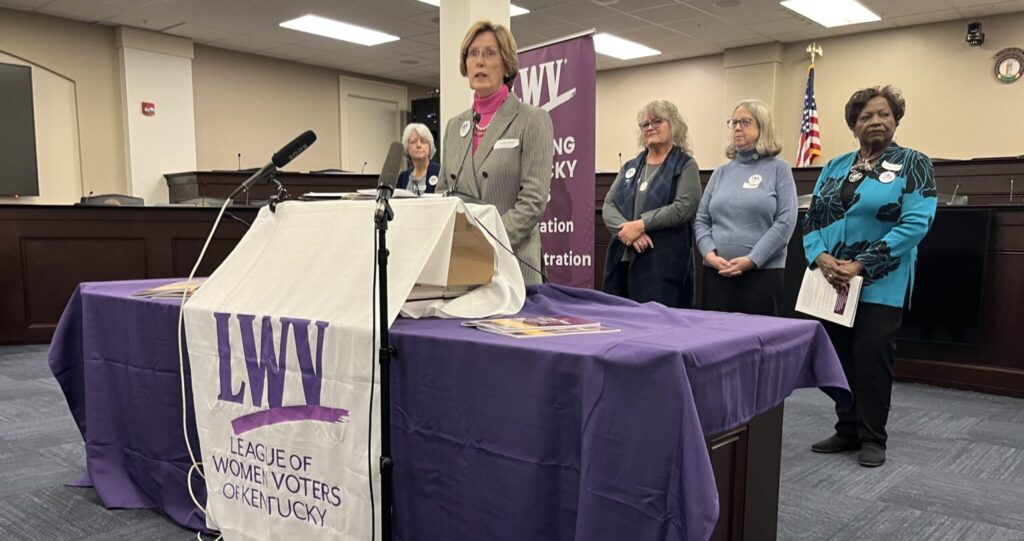

One of the first things lawmakers do at the start of a session is pass the rules that govern the legislative process, said Becky Jones, the first vice president of the League in a news conference in the Capitol Annex. The rules include how bills will be debated and reviewed by the two chambers.

“We suggest those rules to do two things: meet the constitutional requirements for legislation, of course, and provide sufficient time for legislators and the public to review and comment on the proposed legislation before legislators vote on it,” Jones said. “Why? Because legislative transparency equals public visibility.”

The report also notes that some lawmakers may respond by saying such processes have always been this way in Frankfort and that’s why the review included multiple years. The League cited a moment on an April episode of Kentucky Tonight when House Majority Caucus Chair Suzanne Miles, R-Owensboro, recalled that when she first came to the legislature as part of the minority she got “a letter for me to sign off for a commitment to vote for the budget bill prior to ever seeing [the] bill if I was to get coal severance projects in my county…. I have had to vote on bills before that the copies were so hot that you couldn’t hardly touch them.”

State Sen. Robin Webb, D-Grayson, agreed on the show that it is understood that the majority party “can bend the rules,” and that, “it happens in every chamber across the country and in Congress. We all have procedural issues in the 11th hour… and I don’t think it’s going to change regardless of who is in the majority.”

What’s happening: Undermining citizen participation

The League’s report found that four procedural maneuvers do not give citizens time to analyze bill language, give pertinent testimony to legislative committees, give input through phone calls, emails and visits to Frankfort, and alert other Kentuckians about their concerns.

Those four procedural maneuvers that undermine citizen participation were:

- Replacing original versions of bills with last-minute committee substitute versions and allowing little or no time for citizens to review or comment before the committee vote.

- Holding required “readings” of bills before any committee has considered the bill.

- Holding floor votes on bills the same day as committee action on those bills.

- Holding floor votes on free conference committee reports the same day the reports are filed.

The League warned of damage to the “Democracy Principle,” or democracy that relies on “informed and active citizen participation.” With rapid legislative action, this participation can decrease.

The report provides many examples of bills “that are of grave concern” to citizens and advocacy groups that the legislature rushed through in ways that hid the actions from public view and excluded citizen voices, including the infamous “sewer bill” of 2018. It initially addressed “local provisions of wastewater services” but one day late in the session it became an overhaul of state retirement systems that was passed by both chambers that same day. The state Supreme Court later overturned the law, saying the legislature had violated a constitutional provision assuring lawmakers and citizens time to review and comment on a bill before its passage.

An example identified in the report from the 2023 session was the passage of Senate Bill 150, which began as a measure to ban any Kentucky Department of Education guidance against misgendering trans students and became an omnibus anti-transgender bill, which included a ban on gender-affirming medical care for minors and placed new limits on sex education in public schools.

“Near the end of the legislative session, the House Education Committee called a special meeting with less than an hour’s notice,” the report said. “At that meeting, the Committee made substantial changes to the bill, and both House and Senate voted on the amended version the same day, before citizens (and even fellow legislators) could review and comment on the changes.”

The report findings note that some citizens may think the only way to make their voices heard when participation is bypassed is to “disrupt the process.” Going back to SB 150, the report notes that “protestors were asked to leave after shouting and chanting from the balcony.”

“Ultimately, 19 people were arrested for criminal trespassing when they refused to leave,” the report says. “If the legislature increases its use of maneuvers that undermine public participation, we can expect citizens to become disillusioned with the legislative process and increasingly engage in protest and disruptions as a way to be heard.”

Recommendations for lawmakers

The League did identify several ways lawmakers and citizens can increase transparency in the legislative process in the future. Janie Lindle, a member of the report’s research team, said that she did not know if enough lawmakers would be willing to take the League’s recommendations to enact change, but publishing the report to make lawmakers aware is the first step.

“We are aware that something has changed in the last 25 years, and now we really need to be more considerate of the citizens’ right to be part of deliberations,” Lindle said.

The report’s recommendations to lawmakers were:

- Hold the three required bill “readings” after a standing committee sends the bill to the whole House or Senate for a vote. Following the established process can give legislators and citizens time to review each bill and share thoughts before the floor vote.

- Make committee substitute bills available online at least one full day before the committee meeting when the substitute will be considered. Doing that can allow better informed and more relevant citizen feedback on the legislation being considered.

- Allow at least one full day between the last standing committee action on a bill and the House or Senate floor vote on the bill. When a bill receives more than one committee hearing, this step will ensure a brief opportunity for citizen input on the bill version sent for a floor vote.

- Allow at least one full day between free conference committee revisions to a bill and the House or Senate floor vote on that changed bill. Once again, this process change can create an opening for citizens to see the changes and be heard about how those changes may affect them and others.

For citizens who want to increase their political engagement, the League recommended:

- Monitor each legislative session for opportunities to participate.

- Contact legislators any time legislation is rushed, limiting opportunities to participate.

- Support efforts to change these practices, joining with other groups in demanding that legislators follow their own rules — and change the rules as needed to strengthen opportunities for citizen participation. This messaging could be done via social media, petitions, letters-to-the-editor and calls or visits with legislators.

- Engage in peaceful demonstrations and protests.

- Vote for new representatives if the current ones ignore citizens or block citizen participation.

Jones said in the new conference that she corresponds frequently with lawmakers who give thoughtful responses. She added that they were “great examples of how to represent the people” and encouraged more of those interactions.

Lawmakers work for the people they represent, Jones said.

“When it gets to the point where it feels like citizens have to take on a second job to make sure that the people we hired to do the job are doing the job, something is amiss.”

This article is republished under a Creative Commons license from Kentucky Lantern, which is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Kentucky Lantern maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Jamie Lucke for questions: info@kentuckylantern.com. Follow Kentucky Lantern on Facebook and Twitter.