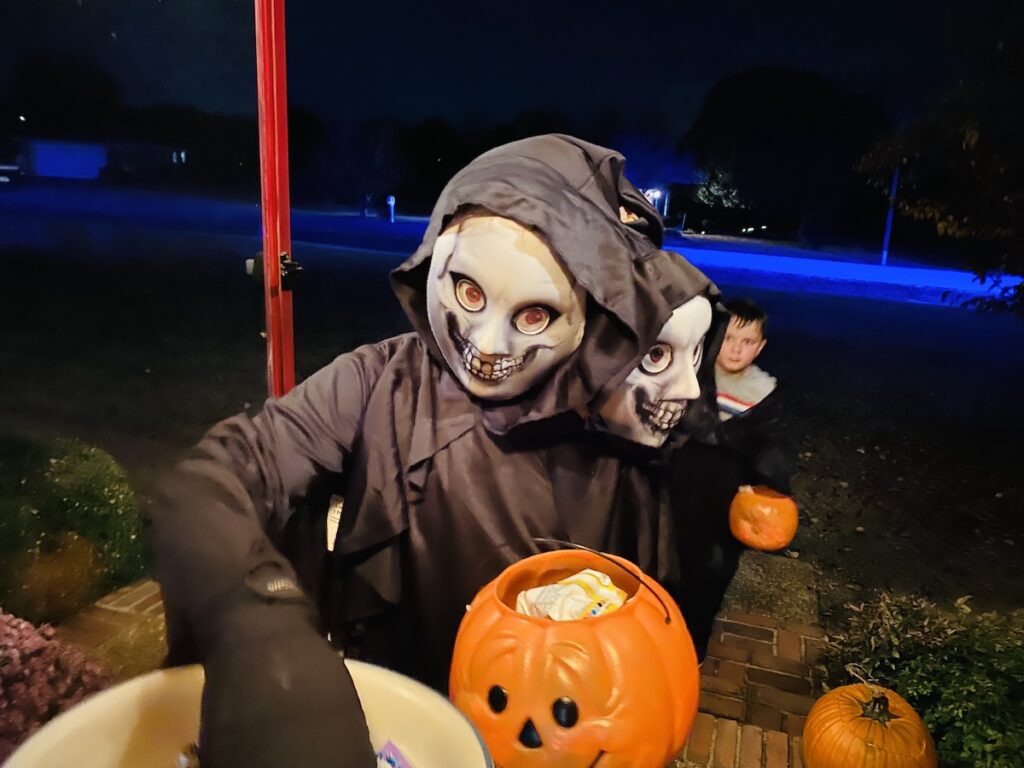

Fall for me as a teenager meant football games, homecoming dresses — and haunted houses. My friends organized group trips to the local fairground, where barn sheds were turned into halls of horror, and masked men nipped at our ankles with (chainless) chain saws as we waited in line, anticipating deeper frights to come once we were inside.

I’m not the only one who loves a good scare. Halloween attractions company America Haunts estimates Americans are spending upward of $500 million annually on haunted house entrance fees simply for the privilege of being frightened. And lots of fright fans don’t limit their horror entertainment to spooky season, gorging horror movies, shows and books all year long.

To some people, this preoccupation with horror can seem tone deaf. School shootings, child abuse, war — the list of real-life horrors is endless. Why seek manufactured fear for entertainment when the world offers real terror in such large quantities?

As a developmental psychologist who writes dark thrillers on the side, I find the intersection of psychology and fear intriguing. To explain what drives this fascination with fear, I point to the theory that emotions evolved as a universal experience in humans because they help us survive. Creating fear in otherwise safe lives can be enjoyable — and is a way for people to practice and prepare for real-life dangers.

Fear can feel good

Controlled fear experiences — where you can click your remote, close the book, or walk out of the haunted house whenever you want — offer the physiological high that fear triggers, without any real risk.

When you perceive yourself under threat, adrenaline surges in your body and the evolutionary fight-or-flight response is activated. Your heart rate increases, you breathe deeper and faster, and your blood pressure goes up. Your body is preparing to defend itself against the danger or get away as fast as possible.

This physical reaction is crucial when facing a real threat. When experiencing controlled fear — like jump scares in a zombie TV show — you get to enjoy this energized sensation, similar to a runner’s high, without any risks. And then, once the threat is dealt with, your body releases the neurotransmitter dopamine, which provides sensations of pleasure and relief.

In one study, researchers found that people who visited a high-intensity haunted house as a controlled fear experience displayed less brain activity in response to stimuli and less anxiety post-exposure. This finding suggests that exposing yourself to horror films, scary stories or suspenseful video games can actually calm you afterward. The effect might also explain why my husband and I choose to relax by watching zombie shows after a busy day at work.

The ties that bind

An essential motivation for human beings is the sense of belonging to a social group. According to the surgeon general, Americans who miss those connections are caught up in an epidemic of loneliness, which leaves people at risk for mental and physical health issues.

Going through intense fear experiences together strengthens the bonds between individuals. Good examples include veterans who served together in combat, survivors of natural disasters, and the “families” created in groups of first responders.

I’m a volunteer firefighter, and the unique connection created through sharing intense threats, such as entering a burning building together, manifests in deep emotional bonds with my colleagues. After a significant fire call, we often note the improved morale and camaraderie of the firehouse. I feel a flood of positive emotions anytime I think of my firefighting partners, even when the events occurred months or years ago.

Controlled fear experiences artificially create similar opportunities for bonding.

Exposure to stress triggers not only the fight-or-flight response, but in many situations it also initiates what psychologists call the “tend-and-befriend” system. A perceived threat prompts humans to tend to offspring and create social-emotional bonds for protection and comfort. This system is largely regulated by the so-called “love hormone” oxytocin.

The tend-and-befriend reaction is particularly likely when you experience stress around others with whom you have already established positive social connections. When you encounter stressors within your social network, your oxytocin levels rise to initiate social coping strategies. As a result, when you navigate a recreational fear experience like a haunted house with friends, you are setting the emotional stage to feel bonded with the people beside you.

Sitting in the dark with friends while you watch a scary movie or navigating a haunted corn maze with a date is good for your health, in that it helps you strengthen those social connections.

An ounce of prevention = a pound of cure

Controlled fear experiences can also be a way for you to prepare for the worst. Think of the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, when the films “Contagion” and “Outbreak” trended on streaming platforms as people around the world sheltered at home. By watching threat scenarios play out in controlled ways through media, you can learn about your fears and emotionally prepare for future threats.

For example, researchers at Aarhus University’s Recreational Fear Lab in Denmark demonstrated in one study that people who regularly consumed horror media were more psychologically resilient during the COVID-19 pandemic than nonhorror fans. The scientists suggest that this resilience might be a result of a kind of training these fans went through — they practiced coping with the fear and anxiety provoked by their preferred form of entertainment. As a result, they were better prepared to manage the real fear triggered by the pandemic.

When I’m not teaching, I’m an avid reader of crime fiction. I also write psychological thrillers under the pen name Sarah K. Stephens. As both a reader and writer, I notice similar themes in the books I am drawn to, all of which tie into my own deep-rooted fears: mothers who fail their children somehow, women manipulated into subservience, lots of misogynist antagonists.

I enjoy writing and reading about my fears — and seeing the bad guys get their just desserts in the end — because it offers a way for me to control the story. Consuming these narratives lets me mentally rehearse how I would handle these kinds of circumstances if any were to manifest in my real life.

Survive and thrive

In the case of controlled fear experiences, scaring yourself is a pivotal technique to help you survive and adapt in a frightening world. By eliciting powerful, positive emotions, strengthening social networks and preparing you for your worst fears, you’re better able to embrace each day to its fullest.

So the next time you’re choosing between an upbeat comedy and a creepy thriller for your movie night, pick the dark side – it’s good for your health.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article here.

Sarah Kollat is a teaching professor of psychology at Penn State. Her areas of specialty include infant, child and adolescent development, and child psychopathology. She has special interests in behavioral therapy, peer relationships, and neurodiversity with a specific focus on the Autism Spectrum. She is a volunteer firefighter and writes psychological thrillers under the pen name Sarah K. Stephens.