LGBTQ people in rural places and small towns are often ignored in the larger conversation surrounding queer life and culture. Even with these omissions, Pride celebrations in those locations are sweeping the nation, often encountering initial resistance.

As a transgender person from Central Appalachia and a doctoral candidate who studies rural transgender media activism, I still find myself sometimes conflating metropolitan with queer, despite knowing that reduces the complexity of transgender and queer lives. The day I reluctantly traveled to eastern Kentucky’s Pikeville Pride, I was doing just that.

Don’t get me wrong; I like myself, and I am proud of the LGBTQ people who are working toward self-respect and celebrating who they are and what Pride represents. Pride’s origin is a commemoration of the Stonewall riots in New York. In June 1969, LGBTQ fought back against laws that prevented them from gathering. That said, I got bored of Pride events – the commercialized type I knew in big cities — and somehow thought that a rural or small-town Pride would be similar.

It wasn’t.

Pride in Pikeville

Before deciding to attend Pikeville Pride in October 2019, I did not understand the difficulties facing those who wanted to host Pride in Central Appalachia and the role of supremacist and white nationalist organizations in that struggle.

Pikeville is a town of about 7,750 in eastern Kentucky. About 400 people attended the first Pikeville Pride event in 2018 and over 500 participated in the one I attended.

Pikeville Pride was held at a park in downtown. Nonprofit groups and grassroots activists set up booths. Free pizza and rainbow-colored cupcakes were offered as bands and drag queens performed on the center stage. Women of different ages were stationed at the Free Mom Hugs table and actively asked attendees if they would like a hug.

Tonya Jones, one of the founders of Pikeville Pride, said she did not start the event in response to the white nationalist rally that was held in downtown Pikeville in 2017, though other founders cite it as a reason. Instead of responding to the rally, Jones wanted to create a more welcoming space in the city.

When I attended, there were no signs of white nationalists or protesters of any kind. Jones said only two protesters attended the first year.

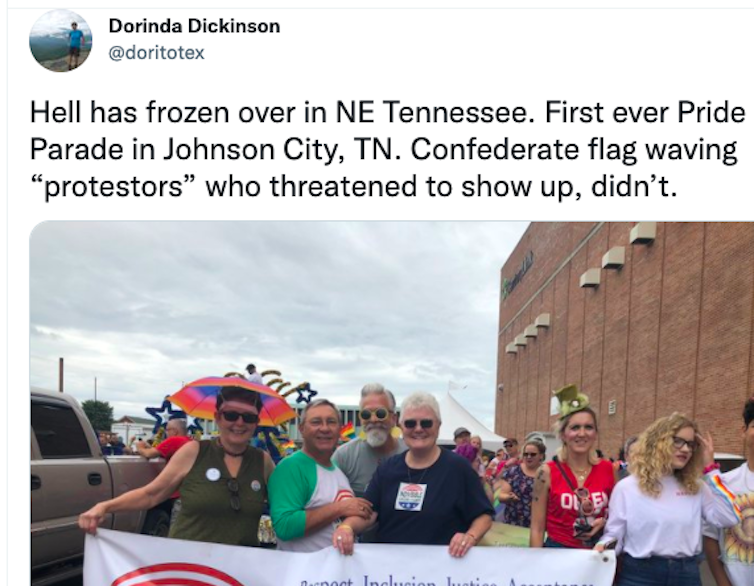

That wasn’t quite the case in Johnson City, Tennessee, a small city about two hours away. In the same year that Pikeville Pride began, white nationalists threatened TriPride, the first Pride event to include Johnson City, Kingsport and Bristol. In the end, 20 protesters attended, according to Jason Willis, the president and a founding board member of TriPride. By the second year, the number dropped to 10 or 12, many of whom stayed in a designated area.

Willis knew the event would attract protesters. “There will always be people who don’t agree with it,” Willis said. “When online chatter of white nationalists happens … well, that’s a different ballgame.”

Because of white nationalist organizing on social media, state and federal law enforcement became involved, Willis says. About 200 police officers showed up during the first event – and a helicopter circled the vicinity. But supporters outnumbered the protesters by a wide margin.

The Pride festivals in Appalachia aren’t the only ones happening in small-town America. Others have occurred in places as far-flung as Window Rock, Arizona; Pocatello, Idaho; Starkville, Mississippi; and Stockholm, Wisconsin.

“I think they are happening because people feel like they can make them happen,” Willis said. “These Prides in small towns will continue to emerge. We had Black Lives Matter and women’s marches. Not that they are the same, but you can have these cultural gatherings in small towns. We’re seeing that.”

Impact of rural Pride

The Prides in small towns are as important, if not more, to queer culture in America as the metropolitan events that happen in June.

In her 1995 article “Get Thee to a Big City,” anthropologist Kath Weston spoke of what she called “the gay imaginary,” the idea that queer people could not be themselves or find community until they moved from their small towns to a big city where other gay people exist.

Jack Halberstam, a scholar of gender studies and English, expanded this concept with the phrase “metronormativity,” in which the journey for queer people from small towns to big cities is a rite of passage.

In essence, cities are allowed to be queer spaces while the rural queer life is ignored, even pitied or rejected, according to Scott Herring, a scholar who studies women, sexuality and gender.

As Herring says, “the rural (take your pick: Idaho, North Carolina, small-town America, hick) is shelved, disavowed, denied, and discarded in favor of metropolitan sexual cultures such as New York City, San Francisco, or Buffalo. In each, the rural becomes a slur, one that has proliferated into an admittedly rich idiom.”

Those lines are reflected in the news and mainstream storytelling. On television, queer characters who left small towns appear regularly, ranging from Titus Andromedon from Chickasaw County, Mississippi, in “Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt” to the “Search Party” character Elliott from a fictional holler in West Virginia. Their background is part of the joke.

But a sense of belonging is not a laughing matter. In Pikeville, Jones knows firsthand what their Pride did for her wife of 27 years.

“She never felt comfortable here until Pride,” Jones said. “She never felt she could be open. We foster children too, and a lot of these kids are in foster care because of coming out. We want to show them that they can have a family, and it doesn’t have to be a blood connection.”

Beck Banks is a Communication and Media Studies Doctoral Candidate at the University of Oregon. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

As a Communication and Media Studies doctoral candidate at the University of Oregon, Beck Banks specializes in transgender media and transgender rurality. Originally from Dolly Parton country, Beck is curious about how rural-based trans media activists understand and work within their communities as well as how they are received by them. Beck frequently collaborates with these activists on projects. To boot, they examine trans television representation and activist efforts — or the performance of those. Having spent years as a reporter and in higher education communication, Beck teaches a variety of courses under the communication and media studies umbrella, ranging from creative strategist to public speaking to media production.