This month’s artifact is easily the oldest that I have featured yet. It is made of wood and covered in hide — some of which still bears hair. Its top is hinged to the bottom with leather straps.

This functional piece measures 23 inches wide by 13 inches deep, standing about 20 inches tall when opened. A handwritten tag is tacked on the top. Based on its style and provenance, we believe it to be from the late 1700s.

This seemingly mundane artifact is a trunk.

To be honest, this trunk has been in the museum’s collection since 2005 and on display since 2020, and I have never paid it much attention. At first glance, it’s just a trunk. Or that’s what I thought until earlier this summer.

Earlier this summer, we hosted the annual conference for the Kentucky Museum & Heritage Alliance and welcomed museum and public history professionals from across the state. The group spent a good deal of time at the Pennyroyal Area Museum, and this little trunk caught the eye of a conference-goer and friend. Zac Distel, who serves as Curator and Program Exhibit Director for the Louisville-based National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, asked to take a closer look.

Zac’s specific interest was in the material used to line the inside of the trunk. He’d hoped to find newspapers from the trunk’s earliest days, but discovered it lined with decorative paper instead.

The information given in the exhibit further piqued our interest — especially when Zac easily convinced me that this simple trunk might have a bigger story to tell.

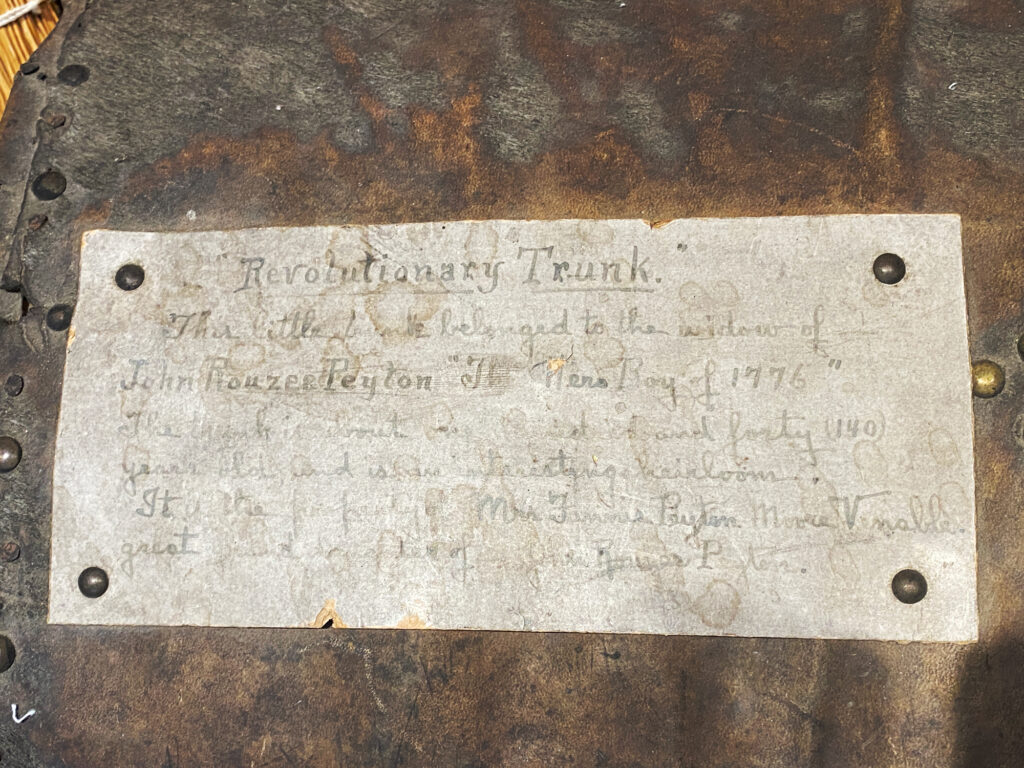

The faded, handwritten tag tacked to the top identifies it as a “Revolutionary Trunk.” A close reading lets us know that it belonged to the widow of John Rouzee Peyton, “The Hero Boy of 1776.”

John Rouzee Peyton

Who were John Rouzee Peyton and his widow, and how were they connected to Hopkinsville?

John Rouzee (or Rowze or Rowzee) Peyton was born in 1754 in Stony Hill, Stafford County, Virginia. The details of his life proved hard to pin down. He was the son of John and Elizabeth Rowzee Peyton, and he married Anne Hooe (or Howe) in 1777. His father was well-established enough to be mentioned in George Washington’s diaries. He operated an ordinary — an early term used to describe a tavern or inn — somewhere along the Aquia Creek in Stafford County, and Washington stopped there on multiple occasions when passing through the area. He lived in Stafford County his entire life and died there in either 1798 or 1799. I feel confident of these details. The rest, I’m not so sure.

Most biographies — including many applications submitted by descendants looking to join the Sons or Daughters of the American Revolution — reference the nickname “Hero Boy of 1776” (found on our trunk’s label) with no supporting explanation. I tried to hunt down the origin of this distinctive monniker. The best I found was in a memoir published by his son John Howe Peyton, who asserted his father served seven years in the Revolutionary Army and “acquired by his dauntless valor and faithful discharge of duty the sobriquet of the ‘hero boy of 1776.’” Some records indicate that he served in the 5th Virginia Regiment, but I could not find any story to connect him to this nickname.

With help from my SAR friend, we checked the DAR’s genealogy database to determine his service during the American Revolution. He is listed as serving as a Justice of the Peace and as providing supplies during the conflict. Sixteen applications list him as a Revolutionary ancestor — many through his daughter Lucy.

‘Hero boy’

I uncovered another story about John Rowzee Peyton that takes a complete left turn from the “Hero Boy of 1776” narrative. This one is sensational, to say the least.

In 1773, after graduating from William and Mary College in Williamsburg, Virginia, Peyton was sent by his father to the West Indies and Jamaica on business. Leaving out of New Orleans, the ship he boarded got caught in a hurricane. The battered vessel was seized by the Spanish, who claimed that the captain and crew were French pirates. They were taken as prisoners into what is today New Mexico and imprisoned in Santa Fe.

Starving and sickly, Peyton found aid from a priest and the daughter of the jailer, who he eventually convinced to help him and an enslaved man named Charles escape. They did, and after five months in prison, they spent almost a year traversing the unsettled plains to get back to Virginia. Along the way, they participated in the Battle of Point Pleasant in the Appalachian mountains of modern day West Virginia. According to this story, Peyton suffered a back injury in the battle that prevented him from military action in the American Revolution. He returned to Stafford County, where he began working as a jail commissioner by 1796. He died a couple of years later at the age of 44.

What a story!

This account of John Rowzee Peyton, written by his grandson, is included in the book, “Peytons Along the Aquia,” and is considered to be partly factual and partly imaginative. A 1991 article in The Santa Fe Reporter goes to great lengths to debunk the story altogether.

You can draw your own conclusions about John Rowzee Peyton and his service in the American Revolution. The big conclusion I’m drawing in regard to this trunk is that Peyton never set foot in Christian County. (That is, unless he ambled through here on his possible escapade back from New Mexico.)

To be fair, the trunk’s information does say that it belonged to his widow Anne Hooe Peyton. Anne was born in 1755 in Prince William County, Virginia. She married John in 1777, and I am unsure how many children they had. They at least had son John Howe and daughter Lucy, both of whom lived to adulthood. Anne died at her son’s home in 1837 at the age of 81. She outlived her husband by almost 40 years and presumably never remarried. Anne, like John, never set foot in Christian County either.

Christian County connection

How are they connected to us?

The answer is a beautiful lesson in genealogy and family heirlooms. John and Anne’s daughter Lucy married Thomas Green, son of Revolutionary War Colonel John Green. Thomas, like Lucy, was born in Virginia, but the two were living in Christian County by 1810. My assumption is that Lucy brought her mother’s small trunk with her when she moved from Virginia.

I followed the family tree from here to get to the gentleman who donated the trunk to the museum. Lucy’s daughter Mary was likely the next keeper of this prized family possession. She married William Moore, and the trunk passed to their daughter Ann Frances “Fannie” Peyton Moore. Fannie married Rev. John Venable, and they had one son, John Wesley Venable Jr. He married Alice Allen Lacy. They had no children. One of their nephews — Alice’s sister’s son — inherited the trunk and graciously sent it back to Hopkinsville by donating it to the museum.

I believe it was Fannie Venable who wrote the note affixed to the top of the trunk. After identifying John Rouzee [sic] Peyton, the note continues, “The trunk is about one hundred and forty (140) years old and is an interesting heirloom. It is the property of Mrs. Fannie Peyton Moore Venable, great granddaughter of John Rouzee Peyton.”

Oh, the stories that this trunk is able to tell!

The local chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution is the Col. John Green Chapter, named for Lucy Peyton Green’s father-in-law. Miss Mary Bronaugh, the first female attorney in Hopkinsville, traced her ancestry back to John Rowzee Peyton, as have so many others in this community. John Wesley Venable, Jr. left a unique legacy to the museum — the miniature circus that he built and displayed in his attic after his father died and he was left to live with his doting mother Fannie. Made up of hundreds of individual pieces, this collection is easily one of the most fascinating that we have. He, too, is connected to this trunk.

Zac was right.

This little trunk carries more stories — about the creation of our nation, about the westward movement from Virginia into Kentucky, about tiny circuses and Spanish jails, and about families connecting generations through heirlooms — than I ever could have imagined.

Alissa Keller is the executive director of the Museums of Historic Hopkinsville-Christian County. She’s a graduate of Centre College with degrees in history and English and of Clemson University/College of Charleston with a master’s degree in historic preservation. She serves on the Kentucky Historical Society and the Kentucky Museum and Heritage Alliance boards.