Gurney Norman and I met in 1975 when I was an assistant editor at Mountain Review magazine and he traveled to Whitesburg, Kentucky from the Bay Area to read his story Ancient Creek for a JuneAppal Record. It was as much party as live recording session. People drove in from Nashville, Lexington, and Louisville to be there. And years later Gurney asked me to remember it as an introduction when the short story was republished.

A good deal of our friendship has been built around remembering things and telling those stories to each other. And perhaps the most noteworthy part of that enterprise was twenty some years of walking tours of Hazard, where we would make a pilgrimage to the grave of James Claiborne Jones, the great badman of the mountains. (Gurney’s grandfather, also Gurney Norman, had typed up Jones’ inspiring autobiography.) Then from the town cemetery we would amble though Hazard pointing out spots where murder, mayhem, perfidy, and all manner of peccadilloes had occurred.

One time we were in front of Hazard City Hall looking across the street at the old Family Theater, recalling the Old West-style shootout between outlaw Tommy Allen Combs and policeman George (from that day forward “Cowboy”) Smith. As we discussed the choreography—both men wounded, collapsed on the sidewalk, and Smith rolling off the high curb for cover when he ran out of bullets—Mayor Bill Gorman emerged from City Hall and gave us both keys to the city. They were impressive; heavy six-inch plated brass with the logo of Oliver Hazard Perry fighting the Battle of Lake Erie, the mayor’s own name, and one end that doubled as a beer opener.

What follows here is a chat prompted by the City of Hazard and the Housing Development Alliance recently breaking ground for a redevelopment project where new homes will be built in a neighborhood to be named Gurney’s Bend, and our taking some time to revisit Gurney’s story from his start in the Allais section of town to his career as a writer and teacher.

Gurney Norman (photographed here by his wife Nyoka Hawkins for Old Cove Press, 2021) is a writer whose novel Divine Right’s Trip appeared in more than a million copies of The Last Whole Earth Catalog. His novel Kinfolks won the Weatherford Award as the Appalachian book of the year. And his most recent book of stories, Allegiance, was published by Old Cove Press and will be re-published this year by Ohio University Press. Gurney lives in Lexington, Kentucky where he is a professor of English at the University of Kentucky.

Gurney Norman: For some reason I have a very good long-distance memory. I remember the remote past. It’s what I enjoy thinking about. I remember when Allais was a thriving coal camp during the war years, two shifts a day at least. And my grandfather from whom I’m named, was the manager of the company commissary, Columbus Mining Company. That was like being in charge of the Kmart or Wal-Mart. Columbus Mining Company was a big corporate enterprise. It had several mines in different counties. I didn’t quite appreciate the extent to which I had a privileged position.

We lived in the second-best house in Allais. And we lived up the hill, not the top of the hill, that was where Mr. Allais lived. But just down the hill, in a very nice two story framed house, lived my grandparents. My grandmother declined to be called grandma. So, she was Auntie. And that made my grandfather Uncle G. And so those names are just planted in my consciousness. I manage somehow to get by in the present and get done what needs to be done, but essentially, I prefer the 1940s.

One of the aspects for kids my age then was we were involved in World War II. In 1941 I was four, and I thought I owned the company store. I’d go walk down the hill by myself. And everybody in the commissary knew who I was. I was Mr. Norman’s grandson and named for him. And so all these miners and their wives and people who shopped in the commissary just teased me, and talked to me, and patted me, and I got way more candy than I should have had.

And the area out in front and down in the slope a little bit was the railroad tracks and just up the tracks was the coal tipple I think in the number four seam. And coal came out of there for forty years.

The tipple was very high off the ground, and so the coal would come out from underground and then be hoisted to the top of the tipple, dumped into the tipple and separated into a block of coal—big block of coal—and what I later learned called stoker coal.

I had such freedom. My mother and father and sister and brother lived in Walkertown, and they had a sort of more regular life. Flora, my grandmother, was way more involved with social life in downtown Hazard. And several evenings a week, she would get in her Buick car and go to downtown Hazard and consort with the Ladies Club and Eastern Star. But my role was to be Uncle G’s pet and his buddy.

So in the evenings, and then once I started first grade, what Uncle G liked to do was listen to classical music on the radio. Then the news would come, but I was sitting very near him and often on the floor at his knee. He would tell me stories from his boyhood growing up in western North Carolina. And, of course, down there were Indians and down there were big bears. He was a really, really good storyteller and I sat on the floor at his knees while he just told stories, new episodes of some saga he was making. Among the favorite stories were Daniel Boone and his opponent, who was also his friend, Red Feather. Red Feather was noble and very independent. And he would play tricks on Daniel Boone.

I was sent to live with Auntie and Uncle G, as they were called, and no one ever explained to me why. It probably was to take pressure off of my mother who had two other children, my older brother Jerry, and my younger sister Gwen, and was a teacher. She taught at Hardburly High School. I think I might be the last one to remember Hardburly, and Combs High School, Viper… many, many schools.

My mother was from Lee County, Virginia, had a college degree, and married into the Normans of Allais and moved over there. She had three children in five years while also teaching school. I don’t know how she did that, but my mother’s story is quite wonderful.

She was a noted athlete. She had gone to LMU, Lincoln Memorial University, and had played basketball, and above all was on the track team. She tried out for the Olympics. There were trials in Johnson City, and my mother competed to be a hurdler in the 1928 Olympics and was very competitive but ultimately did not make the cut.

My mother and father were born a week apart in 1910. LMU had an academy for a while where high school seniors would go for college prep I guess, and so that’s where they met is down at LMU.

There was a younger son, Lucien, who was the handsomest young man there ever was, and Lucien was popular in high school, and he came up here to UK and was meant for university education. My dad was not. He was every bit as smart as his younger brother, but he just wasn’t inclined to go on to school beyond high school. Anyhow, Lucien came up here to UK in about 1930, and was blondish, and very nice looking, and succeeded. He majored in engineering, joined Triangle Fraternity, graduated here, and was destined to go wherever university education would take you at that time.

But then, as a very young man, about 22 or 23, he got tuberculosis. I think in those days, the early and middle ’30s, TB was rampant. And Lucien just got TB and died at age 24 maybe. And this marked the family somehow. My grandmother, my dad’s mother, she never got over it. It was just tragedy struck the family with the death of Lucien, my father’s young brother, I think in 1934.

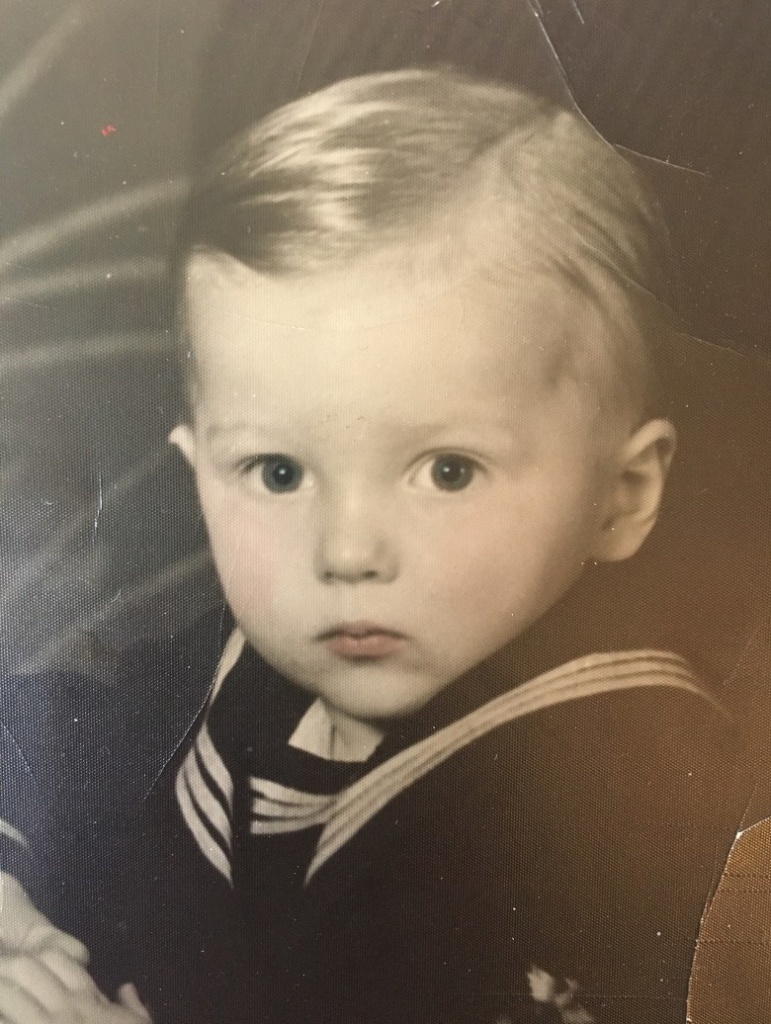

My grandparents never got over the loss of Lucien, and of course for my dad it was the loss of his young brother. Lucien was among the first to be buried up in Englewood Cemetery, and there’s a stone there with the name Norman on it still there. It was always said that I looked like Lucien. I was fair-haired. My brother Jerry had black hair, and my sister brown hair, but I had blonde hair.

He had been dead about three years by the time I was born, and this was a cloud over the family. My father was a thinker. He was a good storyteller. And his life was marked also. He lost his young brother and developed an inward persona we could say. And he was a reader. He read all the time. And also, a very fine writer, letters mostly. I still have many of his letters.

I don’t need to go off on a monologue about it but my mother and father both had very bad luck. My mother developed a mental illness during World War II. And my father was not in the war but he was in the Army. He was not really suited for army training and so forth, he really was an intellectual, but he was also a coal miner and had been a ground pounder during the war. He did not go overseas. I was born in 1937 into a family that was just in permanent grief, so it seemed, especially my grandparents.

In 1946 my grandfather’s health collapsed. He lived on for a couple of decades, but he lost his health, could not work anymore. Which meant that we could no longer live in the company house, so we were kind of kicked out of Allais. And he went to North Carolina where he was from, Avery County, because it was thought that that was the place he could recover his health. And, it meant that Auntie lived beyond in an apartment on the riverbank there across the street from the county jail. And my brother Jerry and I ostensibly lived with her. Our little sister Gwen, had gone to Lee county, Virginia, to live with our mothers’ people. So now, we are a downtown Hazard family, and suddenly we’re poor. We didn’t have our grandfather who managed the commissary.

Dee Davis, Daily Yonder: Oak Ridge, Tennessee had a Class D minor league called the Bombers. They went broke, were purchased, and moved to Hazard. Tell us about your grandmother and the Hazard Bombers.

GN: So to make ends meet, Auntie took in boarders. She had a two-bedroom apartment on the second floor of a building across from the old county jail. She was no longer the Queen of a coal camp. Hazard in the late ’40s and early ’50s, like a lot of the small towns, had professional baseball. The Mountain States League and Class D and so four months out of the year, Hazard would fill up with these 20-year-old baseball players. And they had to have someplace to sleep and didn’t need much. So Auntie, in her two bedroom apartment, rented one of her bedrooms to players for the Hazard Bombers. And I remember from boarding school, I would come down to Hazard. It was called going home, wasn’t much of a home, but her apartment became where I stayed when I was in Hazard. And so I met these baseball players. I slept on the couch because there was a professional baseball player in the bedroom.

A few of them went on to big, big success. I saw Johnny Podres pitch ball. And just the idea of professional baseball in the Mountain States League was a very big deal. We thought we had arrived. We didn’t know it’d only last the three years, but Podres was a star.

[Bomber pitcher, Johnny Podres, became an all-star for the Dodgers and MVP of the 1955 World Series.]

DY: So besides Johnny Podres and your mother being an athlete, you became the quarterback of the Stuart Robinson Eagles high school football team. Tell us about getting to Stuart Robinson.

GN: Auntie was not going to raise us. Something had to be done with these two little boys. The Stuart Robinson School was a Presbyterian boarding school and also the public school for the lower end of Letcher County, Blackey being the nearest city.

The Presbyterians had started a boarding school there in about 1912, up in the headwaters of the Kentucky River on the north fork and in its upper reaches. And it was a great thing. They brought in education before public school education. Our campus was about 25 acres and it was an impressive institutional arrangement. They did it right. They were well funded. There was a dormitory of 24 rooms for the girls and an identical dormitory building for the boys, 24 rooms.

It was just about the time I was 9 and my brother Jerry was 10 and we were nominally in the care of Auntie, our grandmother, who had no resources. They discovered that there was a boarding school 25 or 30 miles on the up river. By 1946 when I was 9, I was so used to being part of a family that was in chaos. Just the roots, the foundations of our family had all been fractured by World War II, and then post-war when my father could not find employment anywhere.

“They had inherited two little grandsons to care for, to raise. But they learned that the church had a school, a boarding school in Letcher County just in time for us to avoid homelessness.”

Gurney Norman

He never found employment again. And finally, was hospitalized in the veteran’s hospital system. And so, this coincides with Auntie and Uncle G, their fortunes just disappeared. And they had inherited two little grandsons to care for, to raise. But they learned that the church had a school, a boarding school in Letcher County just in time for us to avoid homelessness. And so we were sent to live in the boy’s dormitory on the Stuart Robinson school campus. Which was God at work, that there’d be a church and a beautiful campus with brick buildings and dormitories, and all of this security, only 30 miles upstream. I was 9, and my brother was 10 and nobody explained what we were doing. We thought we were out for a Sunday drive, but the car pulled up onto this campus and it’s a beautiful campus. And we got out. And for some reason there were suitcases with us and we were escorted into the boys’ dormitory where Reba McIntyre presided.

And at the moment you think that there are no hopes, the best thing in the world happened, we were handed over to Ms. McIntyre who took us into the dormitory, put us in a room. And we had to learn how to live in a dormitory with 35 other boys. And we thought we had been brought somewhere for a week or just to deal with the emergency. And I stayed nine years and that campus became my home. I grew up on the Stuart Robinson school campus.

DY: Tell us about playing for the Eagles.

GN: I joined the football team as a freshman. My Brother, Jerry was a sophomore and he was a real athlete. And he understood the game. So, we had no tradition, no boys in our school had ever been on a football team before. We didn’t even know how to put our outfits on at first.

Our coach was Harvey Johnson. Harvey was the real deal. He had played football for Duke. He had been a big-time college football player, and he was probably about 35 or 40 years old. He came to Stuart Robinson because he had a religious conversion. He suddenly was filled with the spirit and he found a Christian school to come and start a football program. So, for one school year, our school had a six-man football team. Didn’t win any games but the boys learned how to play. And then the decision was made to have 11-man football. I was an end, that was my natural position. I could catch the ball.

In my junior year I was still an end, and we never could beat anybody. Every now and then we play a good game, but we were playing schools like Whitesburg and Jenkins and so on. One day, we were just getting killed and Coach Johnson said, “Let’s put Gurney in at quarterback.” So suddenly, I’m the quarterback. And we were getting beat and our plays didn’t work, so I called the quarterback sneak and got five yards. I thought, “heck! That wasn’t hard.” So, I then started calling quarterback sneaks.

“Suddenly, I’m the quarterback. And we were getting beat and our plays didn’t work, so I called the quarterback sneak and got five yards. I thought, ‘heck! That wasn’t hard.’ So, I then started calling quarterback sneaks.”

Gurney Norman

And after 20 quarterback sneaks, I thought, “well, I’ll call a different play. Big mistake. I called a different running play and we got whooped bad. There were games where all we could do is just call quarterback sneaks. We no longer even thought about winning, what we wanted to do was to score. If we could just make one touchdown.

What was great about football was practice. We just took practice very seriously and treated it like games. And, in five years, I was on the team for four, we won two games, and mercifully the school dropped football.

DY: So from Stuart Robinson on the outskirts of Blackey, you matriculate to the University of Kentucky campus in Lexington. And there you begin to write.

GN: Well, that’s right. I got to college and I majored in journalism up here. And you know what that is? Courses in reporting, but also feature writing and so on. I was well prepared to come to UK. And to be a newspaper reporter was my specific ambition, because you get to be 20 and you’ve got to think about what’s your job. And so I studied journalism and had major experience in the journalism building to the point that I had keys to the building because I was editor of the yearbook, the 1959 Kentuckian. I also was in the reporting classes and began to write articles, news articles that would show up in The Kentucky Kernel. But the creative writing classes [also] appealed to me. That was part of the English department. I never dreamed I would come back and have a 40-year career teaching the very classes that I had taken.

And let me tell you how it was I could manage to come to UK: It was because of a good liberal program for adult children of veterans. If your daddy died before he could use his GI Bill, the children inherited it. And so, I went to school on my father’s GI Bill, $90 a month. I remember it so well. I went straight to it and stuck with it. And I was well trained. My degree says ADJ, that is, bachelor of arts in journalism.

And in my junior year, I found creative writing classes, writing short stories and they were published in the literary magazine, Stylus. And then as journalism major, I was a reporter for The Kernel. And then my senior year, I was a columnist. I’ll tell you the title of my column if you promise not to laugh: “Much Ado.” I hear you laughing. “Much Ado” was the title of my column, it came out on Thursdays.

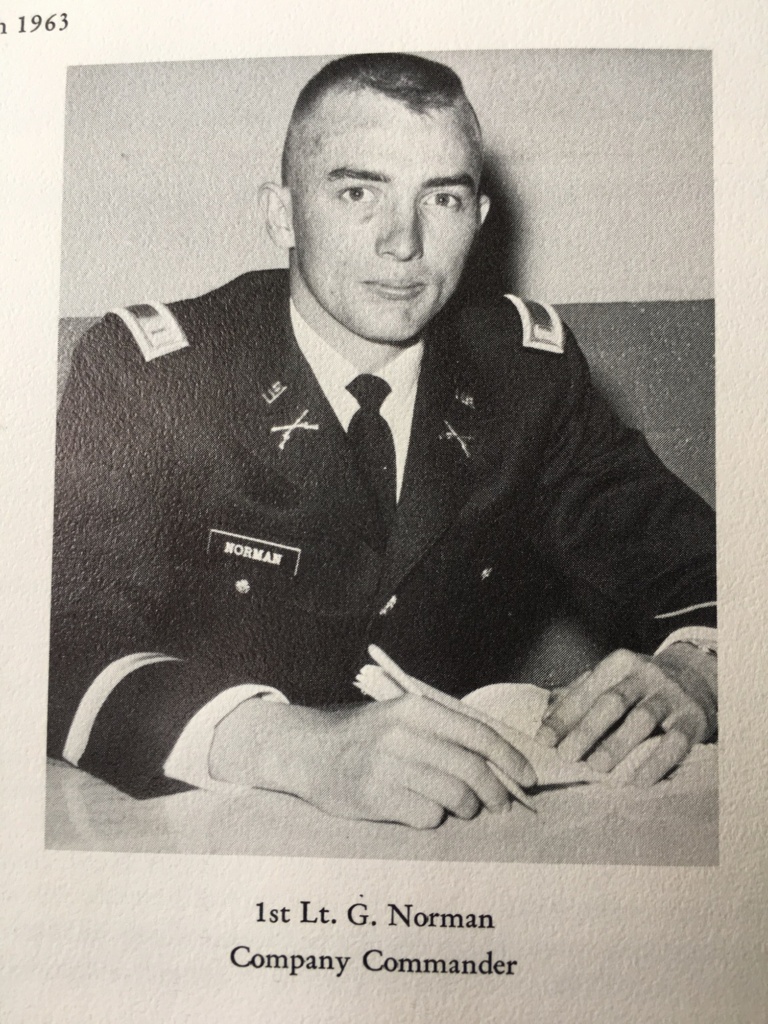

And so I’m 18, I come to UK as a freshman, and I’m not shy. I had lived in a dormitory for nine years and attended boarding school. I had certain amount of social confidence. I got to UK and among the things that I really liked was ROTC. All young male students for two years—this is in the cold war, 1955—were required to take ROTC.

Two days a week, we wore army uniforms. And I did well. I thrived, and I liked the order of it. Anymore, people don’t even know what that means. Reserve Officer Training Corps. It was required. All young American males had a military obligation, it was called, and this meant that if you aren’t in school or something, you were going to be drafted.

And officers have to come from somewhere. They looked at universities to supply them with officers. And so, at UK, I sort of thrived in my obligatory ROTC training. Our country was militarized in a way. I think my boarding school background made me very comfortable with the order of it, and disciplined.

And then, after two years you could volunteer to take advanced ROTC for two more years and emerge after graduation as an officer in the U.S. Army or Air Force. And so, I took the entire four-year ROTC course, and it was good training. We all learned to march. UK looked like Fort Knox on Monday, Wednesday and Friday.

My uncles, all veterans of the war, said, “do you mean you’ve earned a chance to be an officer?” I said, “yeah, ROTC.” And, everyday they were on my case. “And if you are offered a way to get a commission in the U.S. Army, you damn well going to take it.” So, I did what my uncles told me to do.

DY: So how did you get from Kentucky to the prestigious writing program at Stanford?

GN: My writing teacher here at UK was Robert Hazel. I had been with him two or three semesters, written short stories, and he’s the one who told me to apply to the Stanford Creative Writing Program. Wendell [Berry] had already been in that program.

I hemmed and hawed and I finally said, “Well, I don’t think I’m going to apply to that writing program.” And Bob Hazel said, “If you don’t do this, I don’t ever want anything more to do with you.” And so that’s your mentor at work.

Well, it was just sort of the timing and the luck of the draw that I was accepted. The creative writing program at Stanford offered four fellowships a year and you applied for them. And I remember being at UK, writing a letter and putting in a few of my undergraduate stories. The letter was to Stanford University Creative Writing Program, and I had it in my car, but I couldn’t bring myself to mail it. It was addressed and stamped, but I thought I have no business doing this etc, etc. And it fell to the floor of my Ford car under the trash for about a month.

“I hemmed and hawed and I finally said, ‘Well, I don’t think I’m going to apply to that writing program.’ And Bob Hazel said, ‘If you don’t do this, I don’t ever want anything more to do with you.'”

– Gurney Norman

I happened to be visiting relatives in Avery County, North Carolina. I got to Newland and pulled up in front of a drug store. I was longing to go get a milkshake. And right in front of me was a U.S. post box. And then I just thought, “Well, what the hell!” I dug it out and dropped it in the mailbox at Newland. And about three months later, word came that I had been approved for the fellowship to Stanford University. So, my life’s such a pattern, depending on this sheer luck and timing and stuff… And still driving this old red Ford car, I set forth from Lexington. I remember the moment. I said goodbye to some friends, and now I had to get myself to Palo Alto. And, so I did, and my car not only made it there, it lasted another 6 months.

DY: So suddenly you are in a program with top shelf faculty and what turned out to be a murderers row of writers in and around the program including Ken Kesey (One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Sometimes a Great Notion), Larry McMurtry (Lonesome Dove, Terms of Endearment, and Last Picture Show), and Robert Stone (Dog Soldiers and A Flag for Sunrise).

GN: I was there in time to start the fall quarter and a writing class presided over by Malcolm Cowley, and I invite anyone to read up on Mr. Cowley, who was a 1920s Irish American patriot [poet, critic, and editor] in the writing community. And, I might as well go ahead and say it, was friends with Hemingway and Fitzgerald, and of course we tried to get him to talk about those guys.

More significantly I worked with Frank O’Connor, the Irish short story writer. And it turns out that something about Ireland and something about Appalachia fit, and part of it was working class backgrounds. Mr. O’Connor began to give me the time of day. He paid attention to my writing and encouraged me. And I was prolific. That’s all I had to do. I didn’t know how to have a social life or anything. I had this little place to live. That’s just what I did. I just sprawled out words.

But also, in the writing class and in social situations, I was not silent. I was confident, and I talked about Kentucky. I talked about my family background and was very much connected and under the influence of grandparents and my uncles who were World War II veterans, and so I had not spent my life up until then in any kind of privileged situation.

I knew what it was like to be a little bit poor. So, I had what we could call working class background and so did Mr. O’Connor, and we had a lot to talk about, and I began to get interested in Ireland as having something in common with Eastern Kentucky. We connected on what we could call class familiarity.

“I had what we could call working class background and so did Mr. O’Connor, and we had a lot to talk about, and I began to get interested in Ireland as having something in common with Eastern Kentucky.”

– Gurney Norman

It was just a luck of the draw he was there that one time, that one season, six months, 1961, and I’m just wholly indebted to Frank O’Connor and his generosity. He was not an elitist.

And then around the table, there was Ken Kesey from Oregon. And Ken and I were very much alike. Ken had a bigger ego than I did, but Oregon and Kentucky are a lot alike and we naturally fell in with each other. Ken and I became good friends, and Larry McMurtry was a classmate. And he was a Texan and so Oregon, Texas, Kentucky, we had a lot in common and just good fortune and assemblage of like-minded young people who were serious about writing and remained friends. I started to say “for the rest of our lives,” but I don’t want to get ahead of myself.

A couple years later Bob [Stone] and I became friends very, very quickly because by then I lived in Menlo Park, adjacent to the Stanford campus, and was just part of the community. In the 60’s, after coming back to Kentucky, and after serving in the Army etc, etc, I made my way back to Menlo Park, and it just felt natural by then. It was a small town. It was called the peninsula, just San Francisco Bay peninsula. And the Stanford Writing Program, I don’t know about modern times, but in those days it was the glue that held a lot of young writers together in community, and some had such a good time in Palo Alto that they would never leave.

So after I had a fellowship to Stanford in ’60 and ’61, I came back to Kentucky and waited to be called into the Army, and the Army called me and I went to Fort Benning for three or four months. My generation and on up through the 50s, all had what was called the military obligation we owed. And where did the Army send me? They sent me to Fort Ord, Monterey, right back to Northern California. So I was an officer at Fort Ord in ’63 and ’64. I was only an hour and a half drive from my Stanford buddies. I was a soldier during the week, but on the weekends from noon on Saturday, I’d jump in my car and drive 80 miles back up to Palo Alto where I went on with beatnik life, and so I owe a great debt to the U.S. Army for sending me to Fort Ord.

I still thought of myself in terms of journalism because I had experience writing for none other newspaper than the Hazard Herald. And felt confident that I could, as a young bachelor, solitary kind of guy, make my living working for six months for the weekly newspaper and then go off to work on fiction. But I’ve lost my place. Now remind me what we’re talking about.

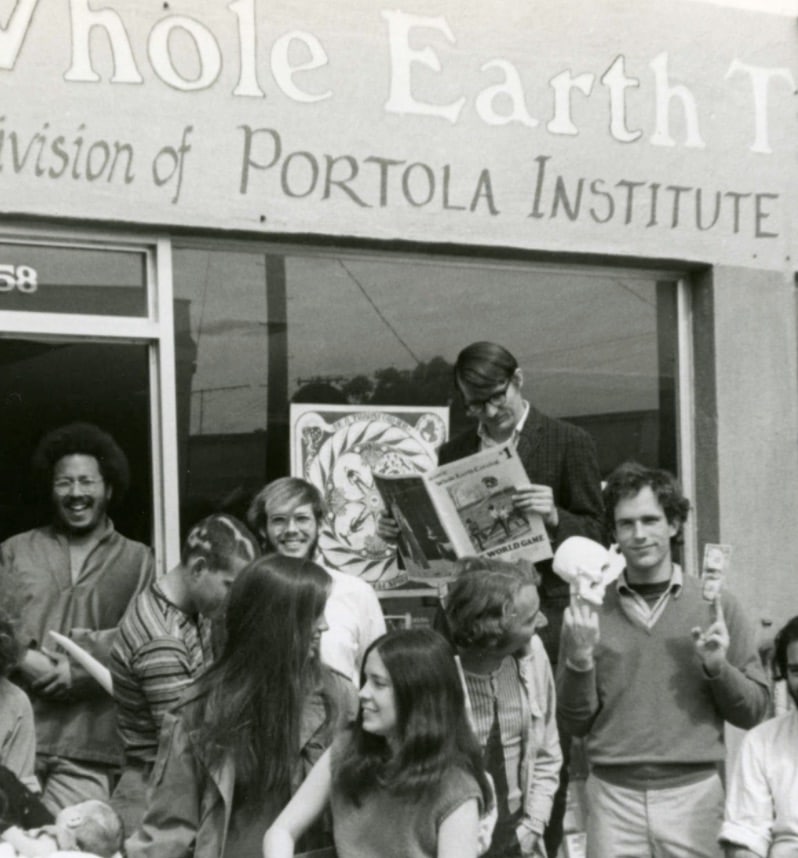

Well, okay. In the community of Menlo Park and Palo Alto and with a writing program that’s been among the best for 50 years, there was just a kind of an understanding. It was not weird to be a writer. Stewart Brand, his own kind of genius, had started a thing called the Whole Earth Catalog, which was a periodical for about two years. It came out, I think, twice a year and it was called Access To Tools, and a good book is a tool. It was a publication being done by young people there, a thin magazine on news print, and that was happening in Menlo Park.

DY: The Last Whole Earth Catalog has been called the paperback version of Google. Scholars have said the catalog’s layout became the architecture for the internet. Tell us about working with Stewart Brand, the publisher, and writing Divine Right’s Trip, the novel that appeared on every other page.

GN: After being back in Kentucky, I was again in California and living in Menlo Park, which was not the Menlo Park we think of today. It had a small town feeling and Stewart was an entrepreneur. He had a good touch. The Whole Earth Catalog was like the Hazard Herald. It was a place to write something and it would be in print, and it was very local. The early issues were just confined to the Bay Area. The whole idea of an alternative part of mainstream culture.

He and I had both been through ROTC and in the U.S. Army at the same time and were the same age exactly. So, we fit as friends. Also, in that community there was a certain interest in psychedelic medicines. So, Stewart and I were buddies in a way, but he was an entrepreneur. He really was organized and focused, and published his catalog. Think of Sears Roebuck Catalog.

I remember where I lived, there was a backyard, and Stewart came around the backyard, and he said, “Gurney, I’m going to kill the catalog with the last issue, and I just wondered if you had any ideas for what it could be.”

I said, “Well, yeah. It ought to have a novel in it.”

And Stewart said, “Fine. Will you write it?”

I said, “Yeah.” And we agreed on deadlines and stuff, and so to make this possible I needed a stipend and so Stewart started paying me $300 a month, which in the ’60s one could live a happy life on that. And so, I just sat down and started making up a story right out of… I don’t know, I just started making it up. And when the chips are down and someone says here’s an opportunity, “Just make it up.” Well, you just start making it up. And it helped that I myself had become a kind of alternative person and had had certain visionary experiences.

Understand that Stewart was a radical, and he was a genius. He also had been a lieutenant in the U.S. Army as I had been. We had many things in common. So, my work was cut out for me. I had this hippie publisher who had had success, had even made money with his publication.

But we weren’t hippies. We were counterculture. Stewart by temperament and knowledge and experience could do things that I couldn’t do. And we agreed on a deadline of nine months. I would produce a novel for the hippie catalog.

DY: So after your publishing success, you get asked to come back to the University of Kentucky to teach. And one of the things I remember from that time was how you used that platform to lift up other Appalachian writers, particularly Mr. Still.

GN: I became aware of James Still quite early. Someone had me read a couple of his stories. Then in 1965, I really wanted to get back to the mountains, and of course I needed a job. And I just wrote a letter to the Hazard Herald, owned at the time by Mr. and Mrs. Nolan. And a summer job was the idea. And so, for the princely sum of $40 a week, I return to my hometown, to Hazard, to be a reporter for the Hazard Herald. I was 28 years old, I think. And I was very aware that over in Knott County was James Still.

I understood that he was a local person, but not a local writer. His books had been published by major presses. And he lived in Hindman, Kentucky. And so, I think it was ’65, I was a reporter. And Mr. and Mrs. Nolan who owned the Hazard Herald were very generous, supportive of me and above all trusted me to know what was a worthwhile story.

I called Mr. Still and made an appointment in ’65 and I said I wanted to interview him. And he was very generous. His presentation of himself was “it didn’t matter if we did this or not.” But when I actually came to Hindman and got with him at the [Hindman] Settlement School one afternoon, he was such a generous hearted, soft spoken man. He treated me exactly right. Somehow, he had a handle on me, and so he agreed to let me interview him.

He had an apartment there on a campus somewhere. But he also had his, I’ve called it a cabin, and I think he called it a house, out in the county. And I got over there in the afternoon and did my work as a journalist or reporter. But also, as my own fiction writer self. And he understood me immediately. He was not defensive. He certainly did not seek publicity, did not even want publicity at all. And on the phone he said, “Well, I don’t ordinarily do this kind of thing, but since you’re local, come on over.” And so in my car, we drove out to his cabin on out in the county and just spent much of the day together, and then I was taking good notes. He was very forthcoming, and I knew about Lincoln Memorial University. I knew that Don West had been there, and that there was a literary tradition at LMU and he had been part of that at some point. So, I was prepared, kind of accidentally, to be able to ask him questions, including about his military experience in World War II. And I was interested in the short story, and I must say I did my part pretty well.

And then I took his picture with a polaroid camera. And he’s out by the well. That was his idea too. “Let’s go to the well,” and he pretended to be drawing water up in a bucket.

And I left my polaroid camera sitting on it and we drove all the way back over to the settlement school campus, and I said, “Oh, I left my camera.” And he said, “Okay, we’ll go get it.” I was dumb enough to leave him my camera, which meant we had to make another trip. But barriers broke down. We wound up the day just feeling like we both lived around there.

Then I left Hazard, went back west and went to Oregon and lived in the lookout tower working for the Forest Service. And I let three months go by, but I had my notes from the James Still interview. And I finally wrote the story, and what better place to publish it than the Hazard Herald? And my polaroid picture of him drawing water up out of his well was accompanying the story. And the story was successful in that it wasn’t a disaster. It came out okay. And I think he was not displeased. And then a couple of years went by and somehow, I was invited to teach for one semester at UK.

Undoubtedly my friend Wendell Berry helped arrange this and Jim Hall, also a writer friend. But it was while I was back. That one semester there was some funds, and I invited Mr. Still to come up to UK to give a reading and he did. I was able to pay him $300 or something. Then the details get fuzzy on me.

DY: Just before the sickness you and your other Stanford writing chum, Ed McClanahan, were inducted into the Kentucky Writers’ Hall of Fame. At the ceremony you read a story from Allegiance, and brought the house down. Tell us about Allegiance and what you are writing now.

GN: I’m very proud of Allegiance, it’s personal, it’s accessible and yet it has some creative moments when I got to play around with language. Well, my books of stories, many of them feature my Wilgus character telling my autobiography. Allegiance came from Nyoka’s Old Cove press. And Nyoka [Hawkins], my wife, is just an ace book woman, designer. And in 20 years has published, I don’t know, 20 books. Beautiful bookmaking, and we’ll be very glad for Allegiance to come out as a hardback book from Ohio University Press.

But I am working on my new book now and it is very pleasing to just have whole new material and to be in the process of just writing new stuff. Part of my UK job is to write and to produce books. My mind, my attention is on my Finley County Record, which is the new work, and I’m writing it in longhand. And what I’ll do is I’ll read you a paragraph from it.

“I’m very proud of myself for coming up with this title because if I have written short stories that nobody else would publish, well, I’ll just put them into The Finley County Record.”

– Gurney Norman

I have a fictional county called Finley County. I thought, old John Finley needed some new place in history, and so I’ve named my fictional county, Finley County, which is in mythical eastern Kentucky. And there is a newspaper published in the fictional Finley County. There’s a fictional newspaper and it’s called The Finley County Record. And so—I’m very proud of myself for coming up with this title because if I have written short stories that nobody else would publish—well, I’ll just put them into The Finley County Record. Now, let me read you a bit from my note here:

“I remember December the 7th, 1941, Uncle G, Mr. Norman, listening to the radio. I felt him respond differently to something he heard. By summer, 1942, I knew we were at war with Japan. July 22nd, 1942 was my fifth birthday. Near that time, I was in a parade down Main Street of Hazard. There was a float built onto the back of a truck, but it was meant to suggest that it was a battleship. And somehow it was pushed by the high school football players, but they were covered by canvas somehow. And so, what it was, was the image of a battleship, and I’m the admiral. I’m aged four and half. They were out of sight. I alone in my sailor suit, was visible to the crowd that lined Main Street. And that was as famous as I’ve ever been. When you’re a commander of a World War II battleship on Main Street in Hazard, there’s nowhere else to go.”

DY: Well, this is wonderful Gurney. I will edit it up, and I’ll make us both look good.

GN: Okay, well that goes without saying. I don’t think anybody can make us look too bad.

Well, this is great fun for me, Dee, and so let’s keep on tracking and hanging out and shooting the breeze.

DY: Good and give my love to Nyoka.

GN: I’ll do.

DY: So long bud.

GN: Okay, buddy. Bye.

Editor’s Note: This interview first appeared in Path Finders, a new email newsletter from the Daily Yonder. Each week, Path Finders features a Q&A with a rural thinker, creator, or doer.