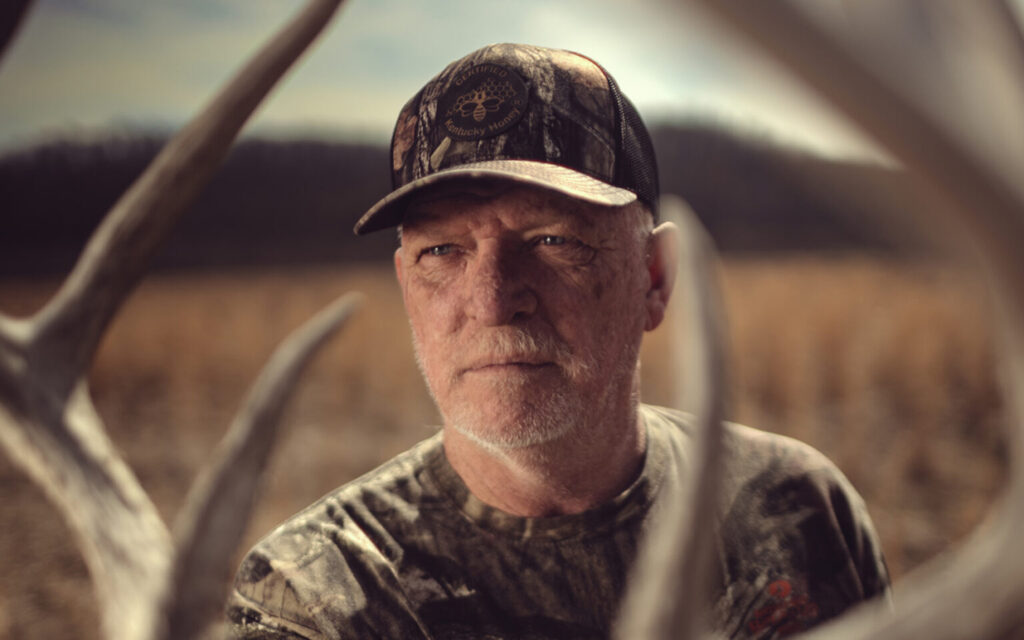

FRANKFORT — Thomas Ballinger, an Army veteran and Butler County beekeeper, wanted to make sure veterans have a voice on the Kentucky Fish and Wildlife Commission, so he threw his hat in the ring for one of the nine seats.

Anyone who holds a hunting or fishing license is eligible to vote at meetings in their commission district. Ballinger finished in his district’s top five top-vote getters, putting him on the list sent to Gov. Andy Beshear, who then recommended Ballinger to the Senate for confirmation.

Then things took an unexpected turn.

- SUBSCRIBE: Sign up for our newsletters

In the final days of last year’s legislative session, Ballinger’s senator, Stephen Meredith, R-Leitchfield, who was working to get Ballinger confirmed, texted him that the confirmation wasn’t going to happen — but not because of anything Ballinger had done.

Meredith said it was because Beshear, a Democrat, had vetoed a bill supported by the Republican-dominated Senate. The measure greenlighted the purchase by the Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources of 54,000 acres of conservation easements in Southeastern Kentucky for $3.8 million. The governor said the bill lacked adequate oversight and cited “past procurement abuses” by the KDFWR. Beshear also cited a 2018 special examination from then-Auditor Mike Harmon, a Republican, who called for a “change in culture” at the agency.

“I had this thing queued up and then the Governor vetoed SB 241 and pissed my leadership off. So, this is a pissing contest,” Meredith said in a March 29, 2023 text message to Ballinger. “They are trying to send him a message and I don’t know if I can turn the tide.”

“Leadership will not yield,” Meredith texted Ballinger the evening of March 29. “It is not you. It’s the governor.”

“If it’s any consolation, there are two others in the same boat,” Meredith texted the next day, referring to two other Beshear appointees who weren’t confirmed, Mark Nethery and Jerry Ravenscraft.

The Senate confirmed only one of Beshear’s four appointments to the commission last year, Gregory Cecil, who filled a vacancy. Commission members whose terms have expired may continue to serve for a year before their seat becomes vacant. Nonetheless, Senate inaction has resulted in three of the nine seats now being empty. A 2022 law mandated that gubernatorial appointees cannot begin serving until confirmed by the Senate.

Ballinger responded to Meredith, saying he felt misled and that the Senate should have been “up front” if it didn’t want to confirm the appointments. He said it was a “sad day” that sportsmen from more than a dozen counties he was set to represent wouldn’t get representation, and that it was “sad that senators let the leadership dictate who represents their district and county.”

Meredith responded: “I can’t disagree with you.”

That was the catalyst for Ballinger deciding to throw his hat into a bigger ring. He’s running for the state Senate, challenging Meredith in the Republican primary in May.

“He represented Senate leadership. He did not represent me,” Ballinger said, referring to Meredith. “The Senate has taken the sportsmen’s choice and the sportsmen’s voice away from them.”

The Senate’s refusal to confirm Ballinger and other Beshear nominees has raised concerns among some sportspeople that the commission is being hijacked by politics, particularly focused on protecting the KDFWR’s chief executive, Rich Storm.

While made up of volunteers, the Fish and Wildlife Commission has far-reaching responsibilities. It oversees the KDFWR’s budget, made up of tens of millions of dollars in hunting and fishing license fees, boat registration fees, and federal grants. It issues wildlife management regulations and hires (or fires) the department’s chief executive. State law directs the commission to keep a “watchful eye” over the department.

The conflict over commission appointments recently flared into wider view when the state Senate narrowly voted to attach the KDFWR to the Kentucky Department of Agriculture headed by Republican Jonathan Shell, moving it outside the Beshear administration.

Under Senate Bill 3, the agriculture commissioner, not the governor, would appoint commission members. The bill awaits consideration in the House.

Beshear has called it a “power grab” and criticized Senate Republicans for refusing to confirm his appointees to oversee KDFWR. “It’s time for them to stop protecting leadership of what I think is the most corrupt part of state government,” the governor told reporters on March 18.

Sportspeople supported a 2010 law requiring Senate confirmation of a governor’s appointees to the Fish and Wildlife Commission. The law also limited commissioners to two four-year terms. Sportsmen say Senate confirmation worked as intended under Gov. Steve Beshear, a Democrat and the current governor’s father as the Senate rejected appointments opposed by sportsmen. Appointment confirmations under Republican Gov. Matt Bevin also sailed through the Senate.

But now some of the law’s supporters fear it’s been “weaponized” and twisted against the votes and voices of hunters, anglers and wildlife conservationists.

“That bill was meant for the sportsmen to be able to reject appointees from the governor that we didn’t like,” said Jim Strader, host of a radio show about hunting and fishing. “It was supposed to be a safety net for the sportsmen, and they’ve turned it into a political football,” Strader told the Lantern.

Rick Allen, a past president of the League of Kentucky Sportsmen, said that with three vacancies on the Fish and Wildlife Commission, there’s “nobody to voice” the opinions of hunters and anglers in those districts.

“It’s supposed to be nine commission members making a decision, one for each of the wildlife districts, and if you’ve got holes there, I mean, people are not being represented properly,” Allen said.

Some Republican senators have bristled at the complaints. Senate Majority Floor Leader Damon Thayer, R-Georgetown, recently said the Senate is not a “rubber stamp” for gubernatorial appointments that should have Senate vetting.

A focus on Rich Storm

The KDFWR, under commissioner Rich Storm, and the Beshear administration have clashed numerous times, on issues ranging from the length of Storm’s contract to executive branch oversight of procurement and conservation easements.

In addition to rejecting Beshear appointees perceived as unfriendly to Storm, the GOP Senate’s support for Storm and the Fish and Wildlife Commission also has included passing laws over Beshear vetoes that give the department independent control over procurements and conservation easements.

In one instance, Senate President Robert Stivers shot down Beshear’s appointment of Hardin County farmer and sportsman Brian Mackey in 2022, suggesting he was a disruptive force on the commission.

open records act to request text messages among commission members, lawmakers and Storm seeking information about Storm’s 2020 contract renewal.

Stivers told the Senate that Mackey had appeared on a segment of Strader’s radio show that “insinuated a lot of bad things.” Strader had criticized the commission’s chairman at the time for downplaying its violation of the open meetings law in a case unrelated to Mackey’s request.

“My understanding from my members on the commission, there is such disruption and consternation that I felt it was appropriate to put this up for a vote now,” Stivers said. He recommended the Senate reject Mackey’s confirmation, which it did, 21-10.

A spokesperson for Stivers declined an interview request about his Senate floor comments and the Senate confirmation process for commission appointments.

Democratic Sen. Robin Webb defended Mackey at the time, saying he was “willing to stand up and ask the questions and not just follow along in line like everybody else.” Webb said that didn’t mean she doesn’t support Storm and the commission.

An analysis by the Lantern found that since Beshear took office, six of his 10 past appointments have not been confirmed by the Senate.

Beshear has five appointments awaiting confirmation in this year’s session, though they would be rendered moot if the House follows the Senate’s lead on moving KDFWR to the agriculture department and giving Shell the appointment power. SB 3 would let Shell make new appointments for commission seats awaiting confirmation this session.

Among the minority of Beshear appointments to the commission that were confirmed, some appointees told the Lantern they weren’t asked about Rich Storm by senators or the governor’s office. But Storm’s job security did come up in 2023 during Senate committee consideration of Mark Nethery, a three-term past president of the Kentucky League of Sportsmen who had been nominated by sportspeople in his district then appointed by Beshear.

The morning before his committee confirmation hearing, Nethery got a call from a fellow sportsman who said lawmakers would question him about his thoughts on Storm.

At the committee meeting, the chair, Sen. Brandon Smith, R-Hazard, asked Nethery if the governor’s office, as rumored, was asking him and other appointees whether they would remove Storm.

“The honest, unequivocal answer on that — no,” Nethery said in response. “That conversation is not taking place with me, between the governor, between boards and commissions or anybody else for that matter.”

Nethery and other sportsmen said it appeared during the committee hearing he was being wrongly blamed for critical social media posts that he did not make. A Senate resolution to confirm Nethery’s appointment never got a vote by the full Senate.

Sen. Julie Raque Adams, R-Louisville, who sponsored the confirmation resolution for Nethery, told the Lantern she was “super supportive” of Nethery but “there was some concern that the governor was appointing people to get rid of the commissioner.”

“He would have been excellent on the commission,” Raque Adams said. “There was some politics going on with the way the governor put forward those nominees. It was just a big hurdle to get over, but I had full confidence in him.”

Meredith also asked Ballinger about Storm in March 2023 text messages, asking if he had “issues” with Storm and saying that his confirmation resolution was being handled by Sen. Brandon Smith, who was “big friends” with the KDFWR commissioner.

Meredith told Ballinger he shouldn’t be worried about the confirmation “unless the Governor has an expectation you will actively work to remove Commissioner Storm from his position.”

“Commissioner Storm is strongly supported by our Republican Caucus; including Senator Smith,” Meredith texted. “Governor Beshear has been trying to remove the Commissioner from office since his election and take personal control of Fish and Wildlife so he can sweep funds from Fish and Wildlife for his personal projects.”

Meredith in a Lantern interview said he was glad in retrospect Ballinger wasn’t confirmed. He revised what he had told Ballinger about Beshear’s veto being the primary reason he wasn’t confirmed. He told the Lantern Ballinger’s antagonistic social media posts — saying he was going to “straighten out” the KDFWR — were the primary reason, something Ballinger said he only posted after he learned he wasn’t going to be confirmed.

In a May 2023 email to Jimmy Cantrell — a past president of the League of Kentucky Sportsmen, a field director for the Sportsmen’s Alliance and founder of the Appalachian Outdoorsmen Association — Meredith was still in tune with what he had told Ballinger. He hated “the political games,” he told Cantrell, and had been “outright lied to” about Ballinger’s confirmation.

Meredith in his email to Cantrell traced Senate leadership’s refusal to confirm Beshear appointees to Beshear’s turning over the entire Kentucky Board of Education, which put in a new state commissioner of education, as soon as he became governor.

“Once he set that precedent, leadership is not going to give him an inch of latitude. I don’t offer it as an excuse as there is no excuse,” Meredith said.

Party politics

The commission, by state law, is supposed to be bipartisan with “not more than five of the same political party” sitting on the commission. Concerned sportsmen say the KDFWR’s mission should be apolitical, focused on preserving and managing wildlife throughout Kentucky.

But the partisan makeup of the board has come under scrutiny in the recent past. Beshear unsuccessfully tried to remove two Bevin appointees, arguing the commission was stacked with Republicans. At least one senator has also suggested that one’s political party allegiance did matter in commission appointment confirmations.

Mackey told the Lantern he changed his party registration from Republican to Democrat before running for the commission to increase his chances of an appointment, given that the commission is required to have a balanced partisan makeup and that Beshear was a Democrat.

Mackey, whose confirmation was supported by sportsmen’s groups, told the Lantern he originally ran for the commission because he cared deeply about the department’s welfare and its “good work,” having decades of knowledge about the department and friends working there.

Mackey said Matt Osborne, the executive director of boards and commissions in the governor’s office, didn’t ask him about Rich Storm when he got interviewed for the appointment.

“I felt like there were some issues that needed to be dealt with, you know, controversy, conflicts, potential corruption,” Mackey said, mentioning he had concerns about how Storm was originally hired. “That’s why I thought I’d be a good commissioner.”

The Fish and Wildlife Commission controversially hired Storm as commissioner in 2019, when he was serving as chair of the commission, after the commission had already interviewed eight candidates for the top post, according to the Lexington Herald-Leader. Storm asked to be considered for the job after the commission named three finalists and recused himself as chair. Storm wasn’t on the search committee seeking a commissioner, according to the department’s human resources director at the time.

Mackey said he didn’t agree with Beshear on much of his policies when he was appointed and spoke out against the governor for an attempted sweep of KDFWR funds in 2020, something a governor’s spokesperson had denied at the time. Republicans have used that incident as a reason for pushing SB 3, the bill giving appointment power to the GOP agriculture commissioner.

Sen. Phillip Wheeler, R-Pikeville, had suspicions about Mackey’s party loyalty nonetheless.

In a Feb. 2022 Facebook message to Jimmy Cantrell, Wheeler said the Republican Senate caucus had heard Mackey was a “Democratic operative” and that “sportsmen need (to be) a bit more careful about who they are sending over for the Governor to pick from.”

Also, Wheeler said another Beshear appointee, Robert Lear, who wasn’t confirmed, was “supposed to be a Republican but was actually a closet Democrat whose wife had called Beshear a ‘sex symbol.’”

That appears to be a reference to a Wall Street Journal article in 2020 headlined “New Cocktail Hour: Your Governor’s Daily Coronavirus Briefing. Live state updates on the pandemic become must-see TV and make unlikely stars of local officials.” The article began with an anecdote of Lear’s wife pouring a glass of wine for her “date” with Beshear, referring to his daily televised appearances during the pandemic.

The article said Beshear had been called a sex symbol, though that description was not attributed to Lear or his wife.

Lear in an interview said he was disappointed he wasn’t confirmed but declined to speculate on the reasons.

Wheeler walked away from a Lantern reporter when asked about the Facebook message and his concerns about Lear’s wife’s thoughts on Beshear.

This article is republished under a Creative Commons license from Kentucky Lantern, which is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Kentucky Lantern maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Jamie Lucke for questions: info@kentuckylantern.com. Follow Kentucky Lantern on Facebook and Twitter.

Liam Niemeyer covers government and policy in Kentucky and its impacts throughout the Commonwealth for the Kentucky Lantern. He most recently spent four years reporting award-winning stories for WKMS Public Radio in Murray.