It is made primarily of metal and stands 4 feet by 8 inches. The top is the real showpiece of this artifact and measures 14.5 inches by 8 inches. It features a handle and three small slits — each sized perfectly for either a nickel, a dime or a special token. A keyhole near its base allows access to the loot deposited inside. The rounded top — painted yellow — displays a timer that accommodates a 60-minute time limit.

Time has expired.

This month, we’re taking a closer look at a parking meter.

I was inspired to dive deeper into the history of parking meters after attending discussions in September with Jeff Siegler, a community planner turned consultant who has written the book “Your City Is Sick.” I attended a session with him, and I was pleasantly reassured when he quickly quipped that Hopkinsville does not have a parking problem. At least, not a problem with a lack of parking.

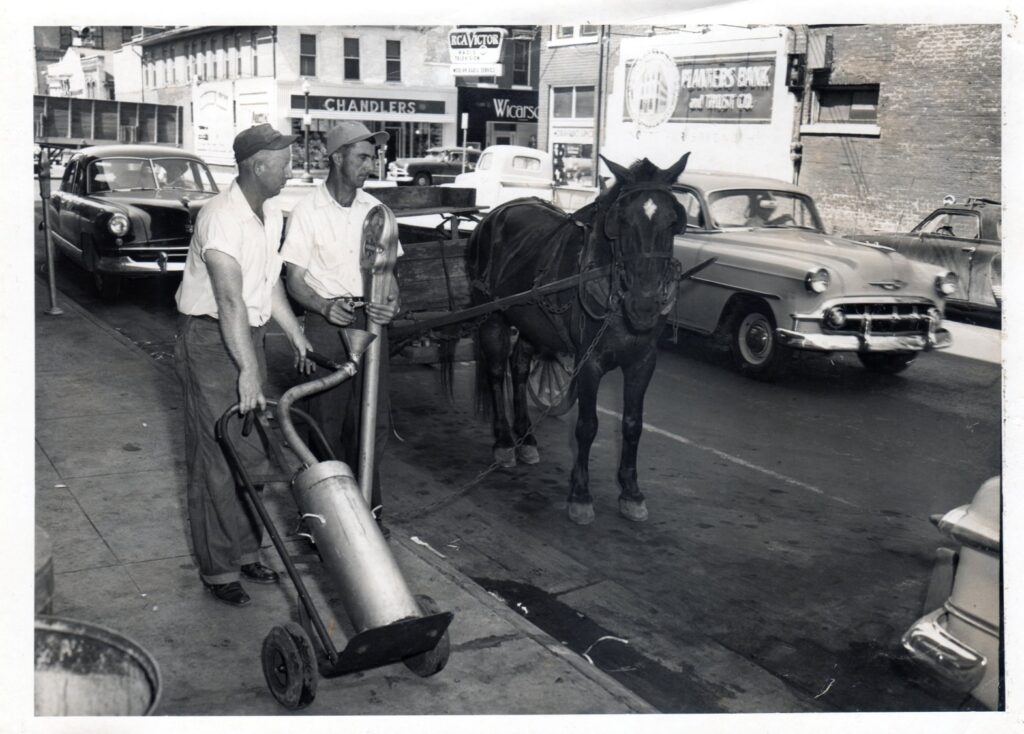

This mention reminded me that the museum has two parking meters in its permanent collection. I have obviously seen them in our storage, and I have even noticed meters in photographs of mid-century streetscapes. I don’t remember them on the streets personally, though. So, when were they in use?

Thanks to a great resource at the museum, I didn’t have to search long for an answer. Years ago, William Turner compiled a long, long list of local events for every day of the year. And yes, parking meters made that list.

The city of Hopkinsville installed parking meters downtown in the summer of 1946. The two meters in our collection were donated to the museum by the city’s public works director in 1986. For 40 years, parking meters dotted our main downtown thoroughfares.

- RELATED: Downtown Hopkinsville: From ideas to action

- RELATED: Downtown revitalization group launches Christmas tree project

A boon to business

The first-ever parking meter was installed in downtown Oklahoma City in 1935. Utilizing a coin-operated timing system, these meters were designed to encourage and improve parking turnover on city streets.

Without regulation, cars frequently parked — and stayed — for hours and hours at a time. The lack of turnover kept streets full and discouraged customers from visiting businesses. These new meters actually proved to increase sales in businesses located on metered streets, and most people welcomed them as a way to ensure access to the places they wanted to go.

Meters also filled city coffers with funds that ideally could be used for improvements to downtowns. It was a win-win situation! That is, when enforcement of meters was consistent.

Initially in 1946, Hopkinsville ordered 274 parking meters at a total cost of $16,566 — paid using the revenue collected from the meters themselves. The city sent the manufacturer 75% of the nickels and pennies deposited in the meters until the debt was paid. It only took one year of downtown traffic and parking to settle up for the meters. One year! In August 1947, the collection from meters was reported to be more than $400 a week. That would be close to $6,000 today.

I haven’t been able to pinpoint where exactly meters were installed, but I know that they could be found on Main and Virginia streets. The newspaper mentions that the initial order was only for 228 meters with 46 devices added to four new blocks of Main and Virginia streets within the first few months.

I decided to take a look at Main and Virginia streets between Fourth and 14th streets to see how downtown changed during the 40 years that parking meters were present. Using a city directory from each decade, I counted the number of addresses within those 20 blocks and compared that to the number of vacancies.

I wanted to see how many buildings were standing, how many businesses and offices occupied those buildings, and how many were left vacant. My goal was to create some sense of evolution — or possibly devolution — of our precious, bustling downtown.

Changing times

In 1946, there were 181 addresses listed on those two streets and within the confines of my study from north to south. Many addresses, like the Phoenix building, boasted multiple tenants, and numerous ½ addresses dotted the streetscape.

In government buildings, entertainment venues, clothing stores, restaurants and bars, the diversity of occupants was immense. Of those 181, seven were listed as unoccupied. That’s barely 4% — meaning 96% of the buildings on those two streets were filled with life. Many of those must have had parking meters outside.

A similar picture is painted in the 1956 directory. Of the 176 addresses listed, nine buildings — or 5% — were vacant.

Things changed by 1966, though. These two streets still boasted 177 addresses, but now 29 were vacant. In 10 years, the percentage of vacant buildings on Main and Virginia streets jumped from 5% to 16%.

Downtown changed yet again over the next 10 years. By 1977, only 11% of addresses were listed as vacant; however, the number of addresses had dropped dramatically from 177 to 110. There were only 102 by 1986, and 19% of those were listed as vacant or with no information available. The city’s vitality and its heart had migrated outside of its central downtown district.

So, what happened? The story here is the same as in so many other towns across the country. The omnipresence of the automobile literally drove us all out of downtown.

In 1960, Indian Hills Shopping Center, the city’s first of its kind, opened on Canton Street — outside of the city’s downtown center. This new style of retail development consolidated business along one thoroughfare, much like a downtown street, but with a massive parking lot in its forefront. In 1969, ground was broken for the Pennyrile Mall on Fort Campbell Boulevard, and the Martin Theater opened there in 1971.

In 1962, Main and Virginia streets were re-routed as one-way streets, allowing for the more efficient movement of traffic through (instead of to) downtown. This change made downtown more convenient for cars and less convenient for people. Siegler brought this up in his discussion, and it was a big a-ha moment for me. Two-lane, one-way streets are meant to move traffic. It is almost like we have an interstate with a 25-mph speed limit running through town with the block between Main and Virginia streets as its median. This change in function completely altered how people interact with our downtown area.

In 1963, the Bassett Urban Renewal Project leveled a neighborhood in the area of First Street to accommodate a new municipal center, post office, police station and fire station. All of these services were shifted from the heart of the business district just to its outer fringes. This project was considered such an improvement at the time that it helped secure Hopkinsville’s designation as an All-America City in 1965.

Based on the decline in the number of addresses by the late 1970s, my best bet is that the 1960s kicked off the big push for businesses migrating out of downtown and removing structures to add surface parking to provide easily visible spots like those at big retail developments. There continues to be rhetoric about the need for more parking downtown. I disagree wholeheartedly. We need more community and more spaces intentionally designed to create community. Parking lots simply don’t do that. Instead, they strip us of our sense of place and of our sense of belonging in this place.

But my guess is that this information about downtown Hopkinsville is not a surprise to any of you. The numbers just prove what we already know because we, as a community, have witnessed it firsthand. And although we have seen the recent razing of more historic buildings, there truly is positive momentum downtown.

I see it in small businesses like Southern Exposure Photography, J. Shrecker Jewelry, and Ferrell’s that have been holding down Main Street for decades. I see it in the movement of the municipal center back into the center district. I see it in the restoration of the Alhambra Theatre and the Pennyroyal Area Museum. I see it in Hopkinsville Brewing Company, and The Local, The Mixer, Big Fellaz, WB Express, the Corner Coffeehouse, Butter & Grace, the Hopkinsville Bourbon Society, and the soon-to-be Crusty Pig.

I see it in the Venue on Main and Studio 3s and in Milkweed and Stella’s Soap and Bella Marie and 6th Street Boutique and Heirloom Table Home. I see it in Planters Bank and in the Kentucky New Era and in Hip Hoptown USA. And that’s just off the top of my head!

Unlike the parking meters in the museum’s collection, time has not expired on downtown Hopkinsville.

Alissa Keller is the executive director of the Museums of Historic Hopkinsville-Christian County. She’s a graduate of Centre College with degrees in history and English and of Clemson University/College of Charleston with a master’s degree in historic preservation. She serves on the Kentucky Historical Society and the Kentucky Museum and Heritage Alliance boards.