Made of elegant peach silk, this long dress is indicative of Edwardian fashion and shows the transition from the cinched waists and bustles of the late 1800s to the looser, shorter, less form-fitting dresses of the 1920s. The bodice features a wrap design with decolletage, or a plunging neckline, that has been modestly covered with an inserted lace panel. Short lace sleeves also adorn the bodice. Its interior structure includes short stays — much like a corset but with less formality. This structure is secured in the back with a series of hooks and eyes and then covered by a silk panel. The skirt has a bit of volume around the hips and rear but tapers down to a more streamlined silhouette towards its hem and short train. An elaborate, ruched waist is accentuated by a periwinkle blue sash made of soft tulle.

This month, we explore the story of a dress.

This stunner found its way into the collection of the Pennyroyal Area Museum in 1996. I had seen it before, but I rediscovered it while Sacra, our collections manager, and I were doing a routine inventory of the museum’s textiles. The dress took my breath away. The soft lines and silhouette, the color, the contrasting sash. It is somehow simple and luxurious. Oh, and the tag sewn inside indicates that it was made in Paris. As in, Paris, France.

I had to know more.

We pulled the deed of gift, our standard document that transfers ownership of items from the donor to the museum, and were pleased to find a handwritten note from the donor. Given to the museum by Mrs. Jean Pinson Askew, the dress belonged to Marguerite Barker Pinson, her mother, who wore the dress at her wedding in 1914. The note gave details as to how, when, and from whom the dress came — and those details just might connect this dress to one of the most famous people and to one of the most notable events of the early 20th century.

Don’t worry. We’ll get to all that.

Even at first glance, this dress proved to be so much more than it appeared. Stored in the same box are a slip, nightgown, pair of silk stockings, pair of satin shoes, men’s dress shirt, vest and two narrow bow ties. The whole kit and kaboodle! While these items don’t necessarily make a complete wedding trousseau, we do have enough pieces to reconstruct much of the bride and groom’s fashion for their big day.

The bride

Marguerite Barker was born in 1887 in the Barker’s Mill community in the far southeastern area of Christian County. She was the youngest child of John Walton Barker Sr. and his wife Frances Elliott Barker and the granddaughter of Chiles T. Barker, an early settler of that portion of the county and the man for whom the mill and immediate community were named. The Barkers and their large extended family owned thousands of acres of farmland in the area.

Marguerite first shows up in the accessible written records in the 1900 census as a 12-year-old who is listed with her parents and as “at school.” I was unable to determine what school she may have attended at the time. A quick search of her name in the Hopkinsville Kentuckian finds her listed as part of a local contingency in 1905 that traveled to Louisville for a large reunion of Confederate veterans, as well as in attendance at parties and social gatherings in the county.

In the 1910 census, she was still living with her parents in Christian County, but that was about to change.

By 1911, Marguerite Barker left the South behind to take up residency in Brooklyn, New York. Again, the newspaper provides a bit of insight by way of a paragraph announcing that her mother was en route to take care of Marguerite who was sick with typhoid fever. The short article, published on Oct. 14, 1911, says that “Miss Barker went to New York several weeks ago to visit relatives.” Marguerite’s older sister Kate had married Harry Schafuss, a Brooklyn man, 10 years prior. While I can’t be certain, I can make a solid guess that Marguerite traveled to New York to see and stay with her sister.

I haven’t been able to find Marguerite listed in a city directory or a newspaper in New York, but I did find her in Clarksville’s Leaf Chronicle at a party around Christmas in 1912. Listed as “Marguerite Barker, of Brooklyn,” she attended an informal dinner given by Mrs. Elizabeth Meriwether Gilmer. Writing under the pen name Dorothy Dix, Gilmer, a native of Todd County, was a journalist who wrote advice columns decades before advice columnists were mainstream. At the time of her death in 1951, she was the highest-paid and most widely-read female journalist with her column running in newspapers around the world.

A notable connection

Lucky for us, that handwritten note on the deed of gift for this dress gave me further clues about Marguerite’s life — and about how she managed to acquire a Parisian dress. The note states that the gown was “given to Marguerite Barker by Mrs. ? Levering, daughter (or granddaughter, most likely) of P.T. Barnum.” As in, P.T Barnum, the founder of Barnum & Bailey Circus.

That is exactly what the note says — complete with the question mark in the place of Mrs. Levering’s first name. I will spare you all the rabbits that I chased to figure out who this woman might be and if, in fact, she was related to P.T. Barnum. Good news! I found answers.

Mrs. Levering was Mrs. Laura Barnum Levering, and she was related to P.T. Barnum. However, their relation was much more distant than the note indicated. Laura Barnum was the daughter of William H. Barnum, who was the third cousin of P.T. And although not the founder of one of the “Greatest Shows on Earth,” he, too, was quite a character.

William H. Barnum was an American industrialist and politician who served in the Connecticut state legislature, in both houses of U.S. Congress, and as chairman of the Democratic National Committee from 1877 until he died in 1889. Some sources say that Barnum was known for political corruption and accused of buying votes. His cousin — the famous P.T. — accused him of such when the two ran against each other for Congress.

He earned the nickname “Seven Mule Barnum” after sending a coded telegram during the 1876 presidential campaign that authorized the purchase of “seven more mules.” The code let the recipient know that he could draw $7,000 more to buy votes from a secret campaign fund. Mark Twain memorialized “Seven Mule Barnum” in a not-so-flattering speech he gave in Boston in 1880.

As a businessman, he owned a leading company in the iron industry, owning or controlling iron mines, charcoal production resources, limestone quarries and rail transportation. He financed a company that manufactured railroad freight cars and founded another corporation that became one of the foremost metal products manufacturers in the world. This Mr. Barnum, for better or worse, was kind of a big deal.

His daughter Laura married Richmond Levering in 1905 in New York. Richmond Levering was a Yale graduate who worked in the oil industry as an engineer, operator, and promoter. He and his wife Laura had 3 children — two sons and a daughter — born between 1907 and 1912.

Mrs. Laura Barnum Levering purchased this peach silk gown in Paris for Marguerite Barker to wear at her wedding in 1914.

The tag inside the dress indicated this all along. Sewn inside the corset structure is a silk tag that clearly states “Paris.” The tag also says “Robes & Manteaux” which I gather translates to “dresses and coats” and gives the street name of Rue Scribe located in the heart of the City of Light. Unfortunately, I cannot make out the designer or shop name on the tag. The way it has been sewn into the dress obscures its name, and no amount of Google searching brought up any definitive answers.

This brings me back to our handwritten note. It continues, “She [Marguerite Barker] accompanied Mrs. Levering and her 2 [sic] children as nanny on trip to Europe in Summer, 1914, and returned when World War I began.”

Wait a minute. Marguerite Barker of Barker’s Mill in Christian County, Kentucky, was in Europe at the outbreak of WWI? And her employer, the daughter of a major politician and industrialist, bought her a wedding dress in Paris while they were overseas? And that dress is in the collection and on display at the Pennyroyal Area Museum?!

It’s almost too much to believe, but the facts check out.

I was able to verify from newspaper accounts and from Laura Levering’s later passport application that she was in Europe from June through September 1914 and that she and her children returned due to tensions with the war. I have not been able to find such documentation for Marguerite. But I do know that she wore this dress when she married William Wallace Pinson at her parent’s home at Barker’s Mill on Nov. 20, 1914.

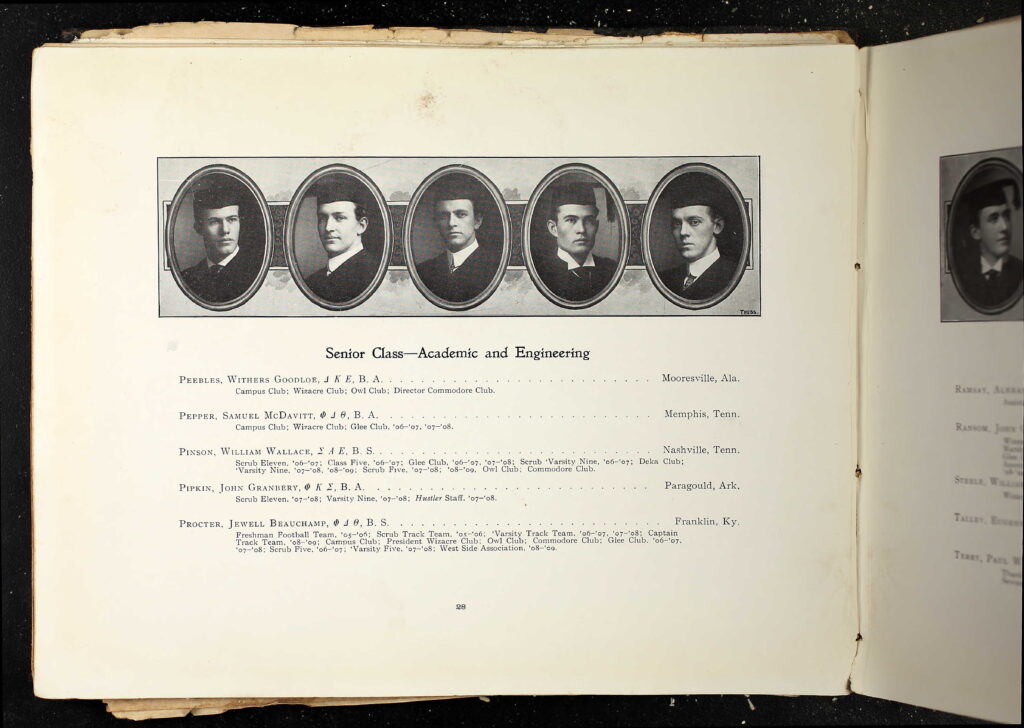

The groom

Born in Texas, Pinson graduated from Vanderbilt University in 1909. Although he lived and worked in Birmingham, Alabama, at the time of their wedding, the couple settled for a few years in the Barker’s Mill area after their marriage.

Sometime after 1920, the couple and their four children moved to Nashville where Wallace worked as an architect in the firm Tisdale and Pinson. The firm designed Central Elementary School in Union City, Tennessee, and Eakin Elementary School in Nashville — both Works Progress Administration projects — in the 1930s. Both buildings are listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

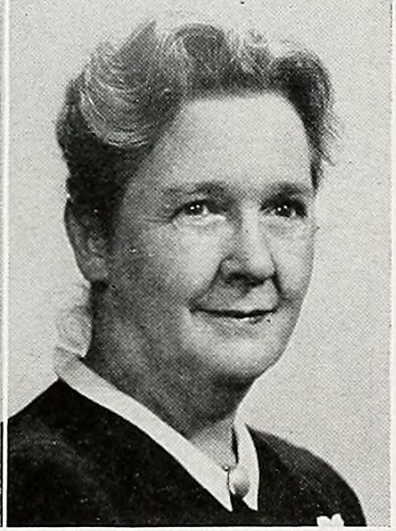

Following a visit to Union City in 1937, Wallace suffered a fatal heart attack. He was only 48 years old. Marguerite was left a widow with four children still at home. I found her still in Nashville in the 1940 census. She lived on Sweetbriar Avenue and did office work for the Methodist Publishing Company. By the late 1940s, she worked as a school librarian — first at Harpeth Hall School and then at Ward-Belmont High School.

Marguerite Barker Pinson returned to her homeplace in Christian County at some point over the next decade. In 1969, her home at Barker’s Mill and all of its contents were destroyed by fire. She was visiting relatives in Colorado at the time.

Marguerite passed away on July 2, 1977, at the age of 89 and was laid to rest in the small cemetery at Chapel Hill United Methodist Church in the Barker’s Mill neighborhood. Her obituary makes no mention of her connections to industrial tycoons or of her days gallivanting around Europe as the entire world turned upside down with the eruption of WWI.

Lucky for us, this peach silk gown survives as an elegant reminder of one woman’s epic, full-circle journey that started and ended in Christian County.

Alissa Keller is the executive director of the Museums of Historic Hopkinsville-Christian County. She’s a graduate of Centre College with degrees in history and English and of Clemson University/College of Charleston with a master’s degree in historic preservation. She serves on the Kentucky Historical Society and the Kentucky Museum and Heritage Alliance boards.