Sixty-two-year-old Rick Turner has seen plenty of sunrises steering his ferry boat, the Loni Jo, between the banks of the Ohio River, a slower routine that he’s grown accustomed to over four decades of work here.

Cars and freight trucks carrying timber pile in a line on one side of the river between rural Western Kentucky and Cave-In-Rock, Illinois, a small town where 18th-century river pirates used to camp out in a limestone cave waiting for unlucky river commerce to float by. The vehicles file on one-by-one, people stepping out to get some fresh air, and eventually the barge is unchained from the dock.

Finally, the power of the boat’s diesel engine roars to life and rattles the wheelhouse. Inside, the gear displays, some of them as old as Turner himself, respond to his touch as he pushes the boat away from the bank for yet another crossing.

He’s well aware that the life of a river ferry captain is a dwindling occupation.

“They’re just not a very common thing to see anymore. They’re just a few of them left,” Turner said. “I think there’ll be a few around for quite some time. Just for that reason that they’re unusual.”

Only five such ferry boats still exist on the Ohio River, and there are only 11 total in Kentucky, Ohio and West Virginia. Some of the ones that are still around, such as the Cave-In-Rock ferry, trace their origins to centuries ago to when the United States’ existence wasn’t even 50 years old.

Turner has seen tourists on his boat from all over come to experience the unique ferry ride, waves of motorcycles during local rallies — “we get swamped with it, man” — and even at one point Juggalos, followers of the Insane Clown Posse hip hop group that flocked to Cave-In-Rock for its annual festival in 2012. His passengers also include locals like Clara Tolbert, 69, who leans over the railing to catch up on the latest with Turner as he pops his head out the wheelhouse window.

“He won’t leave a car behind for one thing,” she said with a laugh.

It’s a boat ride she’s taken since the 1960s and one that she’s shared with her six grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

“They’ve all grown up riding it back and forth, back and forth,” Tolbert said. “It’s just a part of our life.”

But these ferries were a central part of life for many more Ohio River communities generations ago, when they were a necessity for trade and transportation. Unpaved rural dirt roads could turn into impassable mud pits depending on the season. And ferries helped cut down on travel time before bridges dotted the length of the river.

For those that keep the ferries running, the boats hearken back to a slower time and jumpstart the cultural heartbeat of the small communities that keep them afloat.

A world without bridges

Up and down the Ohio River, there are small reminders of where ferry crossings used to be. Several roads along the Ohio River are still named, or used to be named, after ferries or ferry owners, and some communities gave their entire namesake to now extinct boat crossings, like Martin’s Ferry, Ohio and Gallipolis Ferry, West Virginia.

Paul Anderson, the longtime owner of Cincinnati’s only operating ferry on the Ohio River, said there was “probably a ferry every 15 to 20 miles” on the river at one point in northern Kentucky, including small communities like Ghent and Warsaw.

“A typical farmer wanted to go to Cincinnati to the stockyard, they’d go across the ferry. That was the only way to get there,” Anderson said.

The Anderson Ferry was started in 1817 by a man named George Anderson and changed hands before Paul Anderson bought it in the 1980s. He isn’t sure he’s related, but says he wouldn’t be surprised.

“My great-grandfather, George W. Anderson, is buried in the same cemetery down by the ferry,” he said. “He’s only about 15 feet away from the George W. Anderson that started the ferry.”

The original Anderson ferry boat was named after the frontiersman Daniel Boone, a naming tradition they’ve kept up with over the centuries. They’re up to Daniel Boone #9.

“It’s gliding through history you might say, and you don’t know just how many years it could still run, you know, into the future,” Anderson said.

Several Ohio River ferries were operating in the Greater Cincinnati area until the 1960s, Anderson said. That’s around the time when the Interstate 275 loop was constructed around the city and eventually spanned the Ohio River, making ferries less relevant.

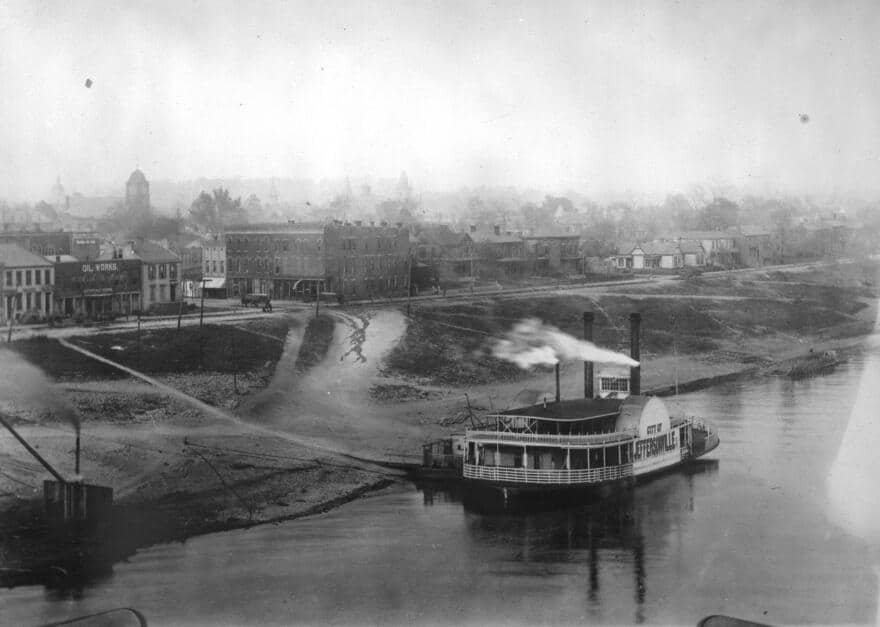

A similar fate played out for the ferries of Louisville, 90 miles southwest of Cincinnati. Travis Vasconcelos, curator of the Howard Steamboat Museum in Jeffersonville, Indiana, said Louisville had four river ferry crossings at one point, and one ran into the 20th century. But in 1929, the George Rogers Clark Memorial Bridge was built across the Ohio River for cars and passengers, almost instantly undercutting the ferry industry.

“The ferry boat business literally dried up and died overnight, and it was kind of sad because it was an over 100-year-old ferry operation,” Vasconcelos said.

Vasconcelos said there’s been a couple of attempts in recent decades to bring back a ferry operation in Louisville to no success.

Bridges spelled the death of other ferries, notably in Shawneetown, Illinois. Vasconcelos said the history and nostalgia of such ferries is worth preserving, helping to remember an era with less modern conveniences.

But for some communities, it takes more than nostalgia to get a community to keep a ferry running.

“If you’re not just preserving a road, a roadway connection between the banks then you have to offer something that gets people involved,” Vasconcelos said. “That’s the sad part because it’s taking away from what the experience really is.”

Finding a way to stay afloat

On the ferryboat crossing the Ohio River at Sistersville, West Virginia, people can be seen having an old-fashioned sock hop, doing “The Twist” in time to the music.

“It’s a cultural icon for this little community,” said Gary Bowden, president of the board that runs the ferry. “I use the term sometimes ‘a West Virginia treasure’ because it’s the last operating ferry in the state.”

Along with providing rides across the Ohio River, Bowden said the company rents out the boat for dances, fireworks viewing and more. They also created a sleek logo for the boat to put on t-shirts and other merchandise.

It’s an evolution for the small community’s ferryboat, which was initially run by a horse-powered treadmill when it first began operations in 1815.

“You can bring a DJ, you can bring a band if you want, any kind of music, your own refreshments,” said Bo Hause, the boat pilot for the Sistersville ferry. “You can cater food, you can grill on the boat if you want. So basically, we supply the boat and the barge and the individual supplies the party.”

The community of a little over 1,000 people have kept it alive in part by renting it out for events, though not without recent struggles. The ferry shut down in 2019 because Hause took another job in trucking. But he came back to take over operations again after a short hiatus.

Ferries like the Cave-In-Rock ferry in western Kentucky are publicly-funded, while privately-owned operations like the Anderson Ferry have the advantage of being a desirable shortcut to the Cincinnati-Northern Kentucky International Airport.

Bowden said the Sistersville Ferry doesn’t make enough money through fares to keep the ferry afloat, and it’s not a vital transportation route, but it’s still a “cultural touchstone.” He said it’s worth keeping the ferry alive through private fundraising and some state funding when other communities have let theirs disappear.

“If they have an appreciation for an earlier time and stepping off the interstate and exploring a little bit of this wonderful country,” Bowden said. “In our case of the Ohio Valley region — then riding the ferry will excite you.”

Liam Niemeyer is a reporter for the Ohio Valley Resource covering agriculture and infrastructure in Ohio, Kentucky and West Virginia and also serves Assistant News Director at WKMS. He has reported for public radio stations across the country from Appalachia to Alaska, most recently as a reporter for WOUB Public Media in Athens, Ohio. He is a recent alumnus of Ohio University and enjoys playing tenor saxophone in various jazz groups.