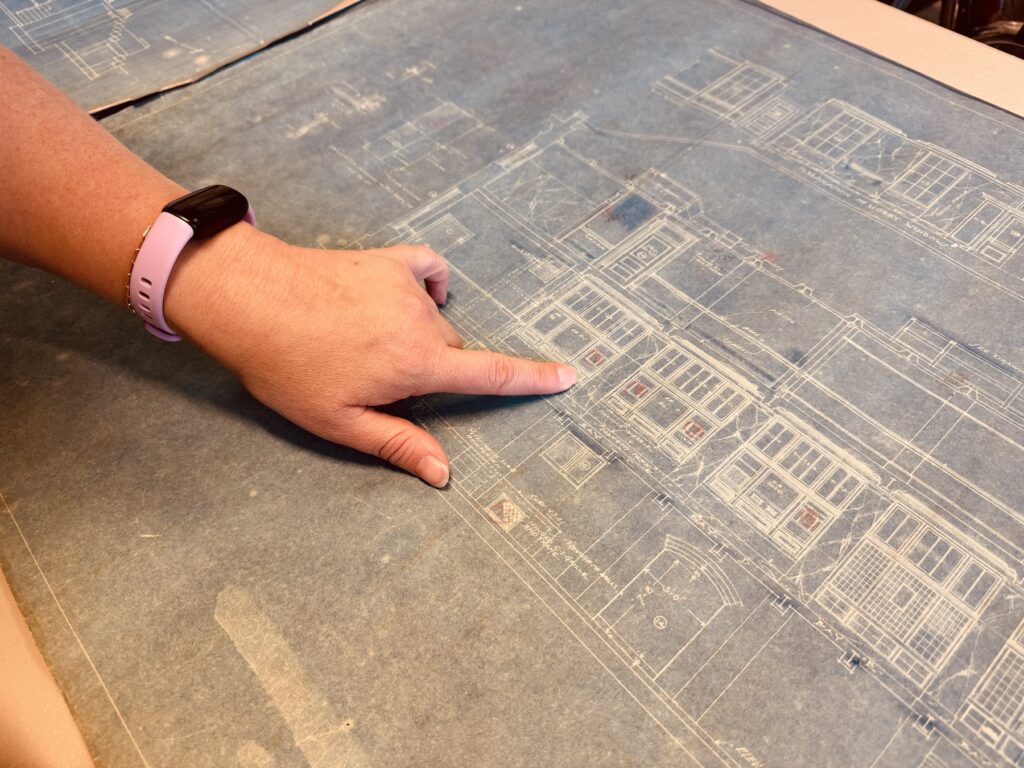

They’re big, brittle, and dirty. These large sheets of paper are the richest blue and show more details than my mind can comprehend.

The biggest ones measure 36 by 24 inches, but a set of smaller ones are included in the vast collection.

Notes are scribbled here and there in pencil and what appears to be red and yellow chalk. The bottom left corner of each page shows the reproduced signature of Oscar Wenderoth, identified as the Supervising Architect of the Treasury Department.

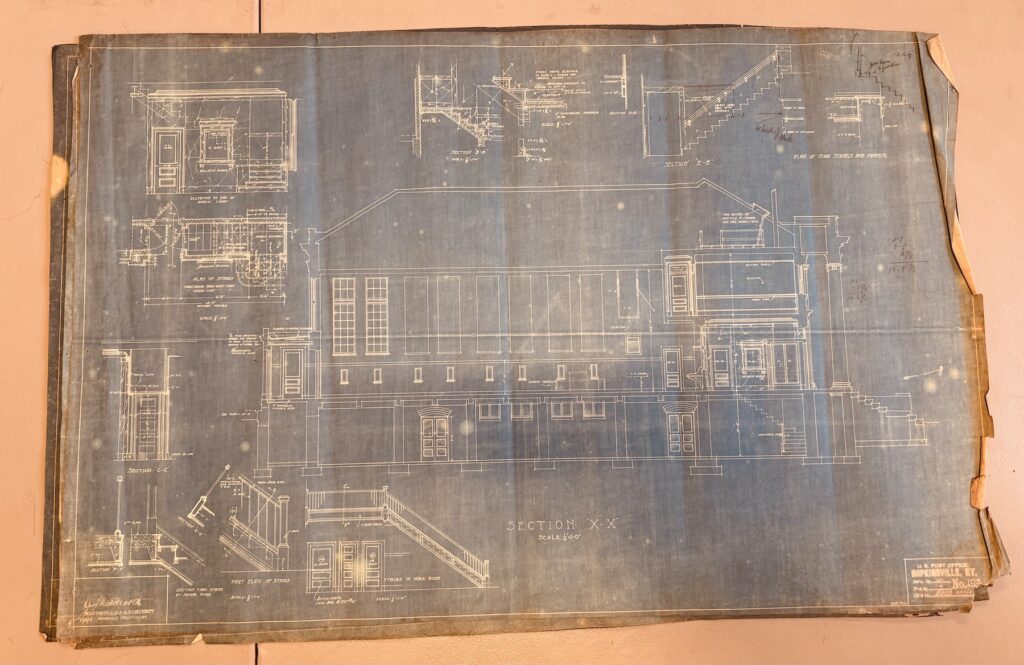

Our artifact this month is an original set of blueprints of the U.S. Post Office building that now houses the Pennyroyal Area Museum.

These blueprints are easily one of my favorite things in the museum’s collection. Found on the floor in the basement shortly after the building was chosen as the site for the Pennyroyal Area Museum, these pages provide so much insight into the construction of this monumental landmark on Hopkinsville’s streetscape. And for an architecture and building nerd like me, they’re just plain fascinating.

All told, there are close to 300 pages of drawings of the building, and they are all in varying stages of deterioration. I guess that can be expected when they were left on a basement floor for half a century.

There is a blueprint for everything: the site plan including removal of the buildings that stood on the lot, the installation of mechanical systems, details of the marble pattern of the floor in the lobby, and elevations of every exterior facade. There is even a blueprint of the boiler in the basement and of the catwalk (titled the “lookout gallery”) in the mail sorting room!

My favorites are the cross sections. These pages show elevations of the building as if it had been cut right down the middle — showing everything from the basement through the attic — a view that is absolutely impossible to see any other way.

The amount of detail that these exhibit is mindblowing. I expect to see accurate measurements and representations of the building elements. Of course. But the fact that the draftsmen even sketched in lines to show the marble on the walls is next level.

The blueprints date to the construction of the post office building in 1913 and 1914. Each unique sheet was drawn by hand by a master draftsman, but there are numerous duplicates of most of these pages. The blueprinting process made it possible to create duplicate drawings efficiently and accurately.

Sir John Herschel developed the blueprint reproduction process in 1842. The mathematician, astronomer, chemist, and experimental photographer invented the cyanotype process for creating blueprints that involves a chemical reaction on light-sensitive paper much like the development of a photograph. In this case, the process is based on a photosensitive ferric compound.

Here’s my layman’s attempt to explain how it works: Paper is prepared with a solution of ammonium ferric citrate and dried. When exposed to light, a reaction occurs that is then developed using a potassium ferricyanide solution. This process creates the Prussian blue that gives blueprints their common moniker.

This method allowed for the rapid reproduction of architectural drawings created by hand. Architects would draw the original on cartridge paper. The originals were then traced onto tracing paper with India ink. The tracing paper was placed on top of the sensitized paper, and both pages were clamped under glass.

And that’s where the magic happened.

The pages were placed in sunlight – for just a few minutes – depending on how bright the sun happened to be. Areas without markings or ink turned blue while those with drawings blocked the ultraviolet light. Where light was blocked, the reaction didn’t take place — leaving the image of the drawing as a negative against the blue reaction. Once a strong image started to emerge, the sheets were taken inside to stop the process. The sheet was then washed to remove the unconverted coating, and bada bing! A copy of the original image that was stable and to scale was left.

Science!

That’s how these blueprints were made, but what do they mean to the greater story of our community?

These blueprints and the U.S. Post Office building represent a time of progress and change in Hopkinsville — and beyond. This post office stands as a reminder of the City Beautiful movement that introduced beautification standards and monumental grandeur to cities across the country in response to the urban ugliness that grew out of the Industrial Revolution.

In Winifred Gallagher’s book “How the Post Office Created America” (2016), she writes that the “palatial new post offices designed for big cities combined beauty, utility, and grandeur to celebrate both the government’s commitment to the people’s good and the Post Office Department’s importance to civic life. No less than Egyptian pyramids or French cathedrals, these heroic American buildings illustrate an institution’s peak and a culture’s moment in time.”

Our heroic post office building certainly illustrated a moment in time for our community. With initial funding received in 1912 until its opening in February 1915, this grand dame of local architecture stands as the first federally-funded post office in Hopkinsville.

At a cost of nearly $100,000 (more than $3 million today), the building served as a cultural center of our community. Correspondence to friends and associates near and far, news good and bad, and even basic money transactions happened inside this building. And in spite of its mighty and formal appearance, it truly was the great equalizer — employing women and African Americans in civil service jobs decades before many other institutions would do so.

The building also epitomized a big building boom in the community, as well as a transitional time as streets saw less and less horses and buggies and more and more automobiles.

The decade of the 1910s came on the heels of the conflict and trauma surrounding failing tobacco prices and the violence of the Night Riders and ended with America’s entrance into World War I in 1917, the Spanish flu epidemic of 1918, and national Prohibition in 1919. News of all these events surely traveled through the doors of this building.

But it was those in between — from about 1912 until 1917 — that were such a progressive, forward-thinking time in Hopkinsville. One might call it a metamorphosis of culture.

Its service as a post office concluded in February 1967. For a period of time, the building served as a servicemen’s center before being sold as surplus property by the federal government to the city of Hopkinsville in 1975. This transfer of ownership required that the building be used for educational purposes.

On July 8, 1976, the building met that requirement and transitioned into a new life of service to Hopkinsville as the Pennyroyal Area Museum. We strive to maintain the building’s status as a cultural center and as a place that seeks out the stories of the community. We hope to breathe life back into the places and objects that our people left behind — including a set of documents left on our basement floor.

Alissa Keller is the executive director of the Museums of Historic Hopkinsville-Christian County. She’s a graduate of Centre College with degrees in history and English and of Clemson University/College of Charleston with a master’s degree in historic preservation. She serves on the Kentucky Historical Society and the Kentucky Museum and Heritage Alliance boards.