In the fall of 2001 the University of Kentucky issued an ebullient press release about an ambitious and unique project.

“A 117-acre family farm was donated to UK for tall grass prairie restoration,” the release proclaimed, about the land in Logan County. “It will be the first of its kind in the state.”

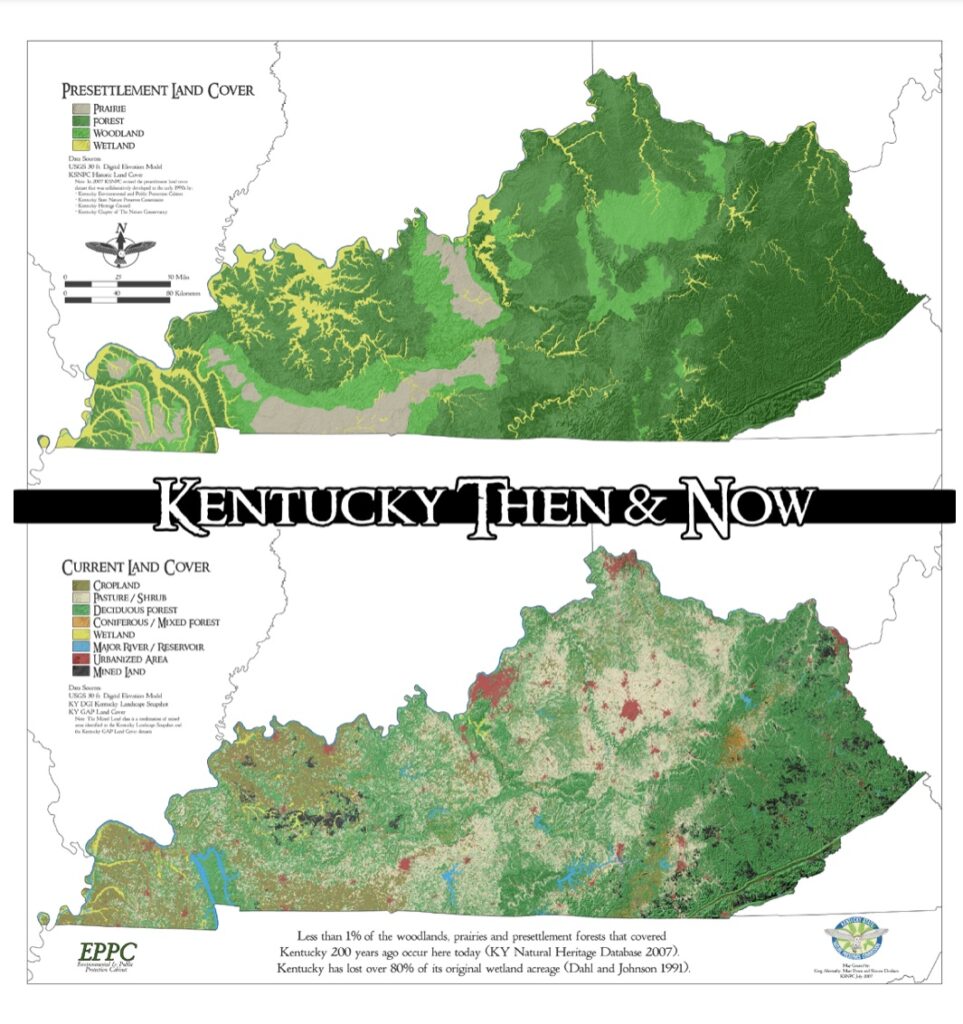

There was reason to be excited. Prairies — also sometimes called barrens or grasslands — had been abundant in Kentucky and across the nation before Europeans settled the continent. Estimates are that as much as 3 million acres of what’s now Kentucky might have been prairie. But by the time of the announcement only a tiny fraction of that remained.

Adding to the optimism, the land, to be called Hall’s Prairie honoring the family that donated it, was to be managed by Tom Barnes from UK’s forestry department, a renowned biologist, photographer and advocate for wild places.

“Prairies hold a special place in my heart,” Barnes wrote the following year in his book, “Kentucky’s Last Great Places,” explaining that he had grown up on the prairies of South Dakota. He appreciated the sweeping view, the “spectacular floral displays or picture-postcard images” that mountains, forests and waterfalls offer but the prairie is more subtle, Barnes wrote. “You have to experience the prairie closeup to really appreciate it.” And, in Kentucky, he said, “we have precious few prairies left.”

No wonder, he wanted Hall’s Prairie to be a place where people could walk in a prairie, have that closeup experience. By the time of the announcement, 4-H kids had already started planting wildflowers and there were plans for trails for the public.

But the vision for Hall’s Prairie didn’t materialize. Barnes died in 2014 but apparently his plans had already stalled as the vision butted up against public concern and the difficulty and expense of recovering prairie land.

Disturbances maintain prairies

The fate of Hall’s Prairie is in many ways the fate of millions of acres of prairie across this nation in the last few centuries.

Relatively flat land, often with very rich soils, the prairies offered prime acreage to plow up for farmland or pave over for development as Europeans spread across the continent.

Modern development also undercut critical tools that keep prairies from morphing into woodlands, said Zach Couch, executive director of the Kentucky Office of Nature Preserves. “A prairie habitat is typically maintained by some sort of disturbance,” he said. Before Europeans arrived, those included fire, a common land management tool of Native Americans that didn’t harm the roots of grasses but destroyed young trees. There were also vast herds of larger grazers — bison, white-tailed deer, Eastern elk — that roamed and preserved the prairies but didn’t survive the onslaught of settlement.

In the modern era maintaining a prairie means “you’ve got to do a lot of intensive management,” said Jeffrey Stringer, chairman of UK’s Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, who knew Barnes and visited Hall’s Prairie with him several times. That management includes using herbicides and regular burns to control unwanted species, he said, and “it has to be done periodically forever.”

As Barnes began the effort to return farmland to prairie, people living nearby complained, particularly about the burning. There was a lot of reaction on social media and elsewhere, Stringer said, “in a negative way.” With no endowment to support the intensive management, local pushback and property that was so far from UK’s campus in Lexington, the question of whether to continue was “a difficult one,” Stringer said. The management was abandoned even before Barnes’ untimely death at the age of 56.

A few years later Stringer tasked a new faculty member with reevaluating the project. They held a public meeting and again found strong opposition to the managed burns. They visited with the land donor, who had moved to Indiana but was aware of the local pushback. Ultimately they recommended to the UK board to sell the land and use the proceeds to create an endowment, named for the donor, for wildlife research and education. The board accepted the recommendation, the land was appraised at about $700,000 and in December UK received several proposals to purchase it but hasn’t yet decided its fate.

Deep roots trap carbon

It’s a sad story, made sadder by Barnes’ early death, and even more so by the challenges faced by the prairies he loved, appreciated and tried to preserve.

Barnes had good reason, beyond their beauty, to champion prairies.

“There’s about a hundred good reasons to preserve prairies,” Couch said. For the sake of brevity, he focussed on two.

First, there’s biodiversity: “The sheer species richness is significantly higher than woodland habitat,” he said, “and obviously a great deal higher in species richness than an agricultural field or a parking lot.”

In “Kentucky’s Last Great Places” (University Press of Kentucky), Barnes described a prairie remnant he visited in Western Kentucky.

“What a beautiful limestone slope prairie! The deep soils were dominated by big bluestem and Indian grass. Little bluestem dominated the upper slopes. Prairie flower, including blazing star, rattlesnake master, and American agave were scattered everywhere.”

Couch said the abundant grasses and wildflowers make good homes for an array of invertebrates, including the monarch butterfly, which the National Fish and Wildlife Service in December recommended be placed on the endangered species list.

The second reason is a little more surprising. “Carbon sequestration is often higher in a grassland community than a woodland community,” Couch said.

“Unlike trees, grasslands store most of their carbon underground, in their roots and the soil,” the Washington Post reported in a 2020 story on efforts to preserve and restore prairies. The roots can often reach 15 feet deep into the earth, so the carbon stays put unlike in a forest which billows carbon into the atmosphere as it burns.

Although programs exist to subsidize forests as carbon sinks, there is relatively little support for using grasslands to capture carbon.

Couch said his office does manage several prairie sites in Kentucky but preserving them, including conducting the regular burns, is a lot more labor intensive, and therefore expensive, than managing woodlands.

So, what to do? “The easy response is additional funding,” Couch said, but added that he’s grateful for the support the legislature already provides his agency. On the private side, he said, there’s “a really good but really small conservation-minded community in Kentucky. The work far exceeds the number of laborers right now.” And there are even fewer private advocates or donors who are focused on preserving Kentucky’s dwindling prairies.

In an early chapter of his book, Barnes explored the reasons why a society should commit to preserving biological diversity. A scientist, he catalogued how our species depends on an abundance of other species to survive, then he went on to argue for the aesthetic value of wild places. “We are outraged when vandals attack precious paintings or sculptures,” he wrote and then hammered home his argument: “Have you ever looked closely at a monarch butterfly, a lady’s slipper orchid, or a Kentucky warbler? … Shouldn’t we protect them?”

His final argument was entirely personal: “For me, it is an ethical issue. The good Lord gave humans dominion over the plants and animals. … It is our duty to be good stewards.”

This article is republished under a Creative Commons license from Kentucky Lantern, which is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Kentucky Lantern maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Jamie Lucke for questions: info@kentuckylantern.com. Follow Kentucky Lantern on Facebook and Twitter.

Jacalyn Carfagno has been a journalist for more than three decades, writing about business and economics, land use and development, food and culture, among many other topics. She has received state, regional and national awards and recognition for her writing and editing. She is a freelancer for the Kentucky Lantern.