Its pages are tattered, and the corners where page numbers should be are completely missing. The cover detached from the book long ago, leaving its marbleized finish warped. The pages have somehow remained bound together — but in three separate chunks.

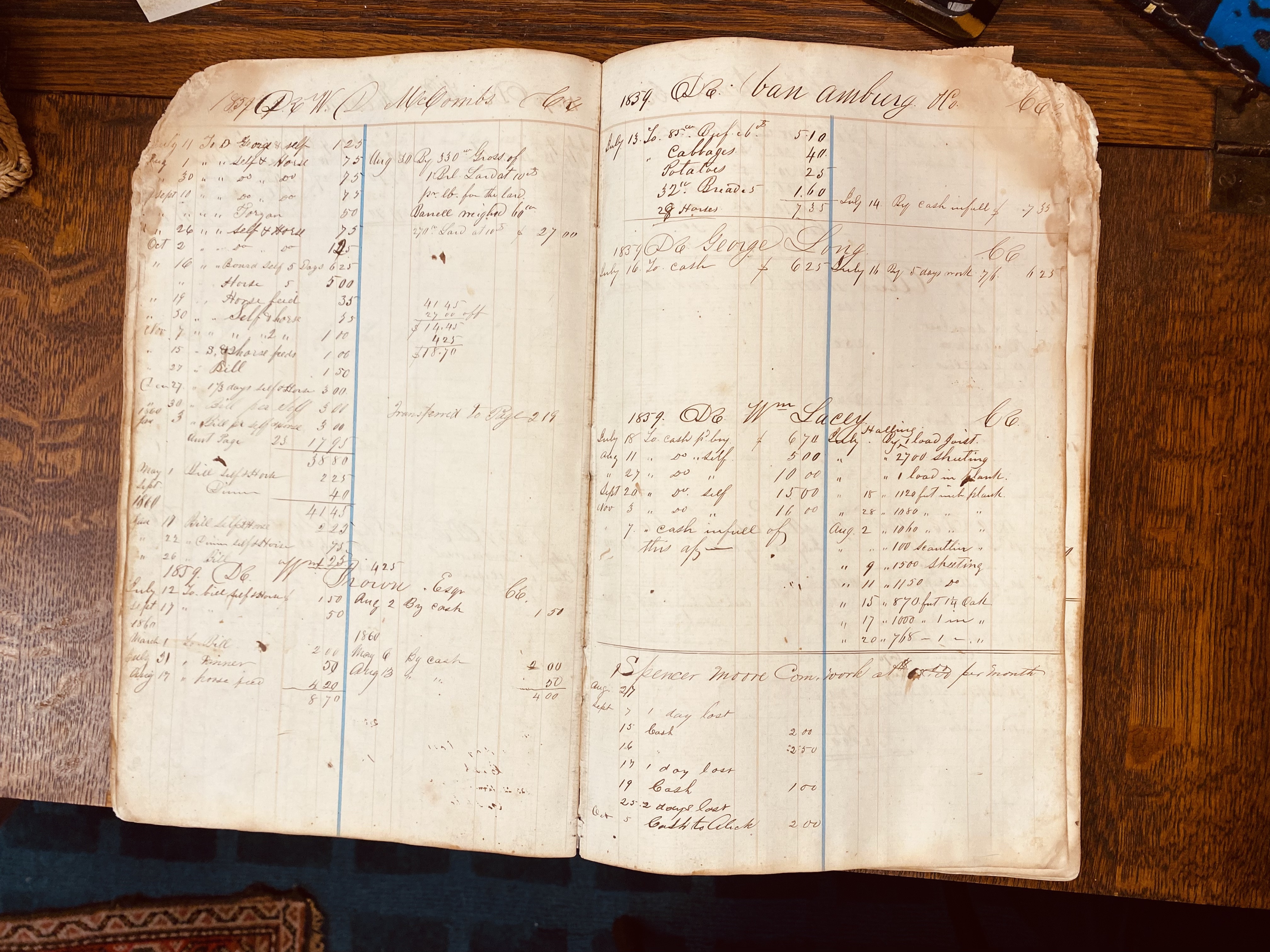

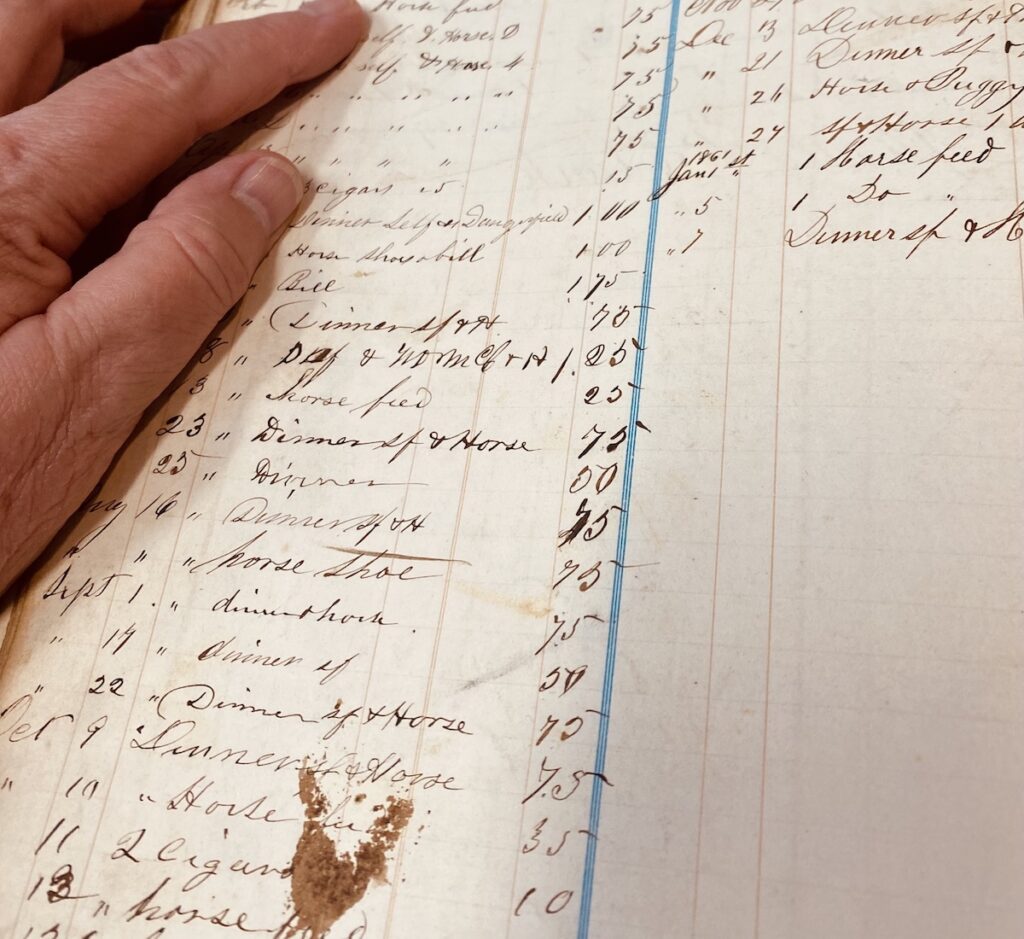

Beautiful cursive handwriting covers the pages, divided into two clear columns. Names are scattered everywhere. So many names. Most without any additional information. The book measures roughly 8 inches wide and 13 ½ inches tall. It is dirty and stained but, overall, in great condition considering its age.

This month’s artifact is a ledger.

Back in January, Hoptown Chronicle editor Jennifer P. Brown and I thought it would be fun to let you choose an artifact for me to study and share. Options included a violin, tombstone, wheat sack, small circus figurine and this ledger. We think identifying it as “a long lost ledger from an old Hopkinsville stagecoach stop” upped the ante on intrigue for everyone. And I am so glad for that.

To be honest, this is the artifact that I would have chosen, too. It has been on my list of things that could tell a great story all along, but it seemed like a behemoth of a task.

The ledger is old. Really old. 165-years-old old. It is fairly fragile, and it is jam packed with information. All told, the ledger holds about 400 pages — each one covered with handwritten details about the comings-and-goings of people in Hopkinsville at the outset of the Civil War.

On these pages are the names of more than 500 people — men, women, doctors, drivers — each with his or her own story to tell. Many names are familiar to our county, but others are listed as traveling from as far as New York and Philadelphia. There is enough fodder in this ledger for a book!

Where could I even begin?

A hidden treasure

Let’s begin with how this ledger made its way into the collection of the Pennyroyal Area Museum. Donated by Mary Edith Sivley, this ledger was discovered during a renovation of her former house.

The house stood on today’s aptly named Sivley Road off Fort Campbell Boulevard and behind the string of hotels and restaurants between the parkway and the bypass. Constructed in the 1840s by James Ellison, the farm was purchased by Burwell Clark Ritter in 1854. When the Sivleys acquired the property in the late 1930s, this ledger was discovered in the attic of a portico as it was removed.

The ledger has been at the museum for 10 years. It recorded the financial transactions of the Ritter House, a boarding house located in the heart of today’s downtown. I am calling it a boarding house — and admittedly, that may not be the best way to describe it. But it was far from a hotel by today’s standards. It was basically just a big house with a few extra amenities that offered a safe, reliable place for travelers — and their horses in many cases — to eat and sleep.

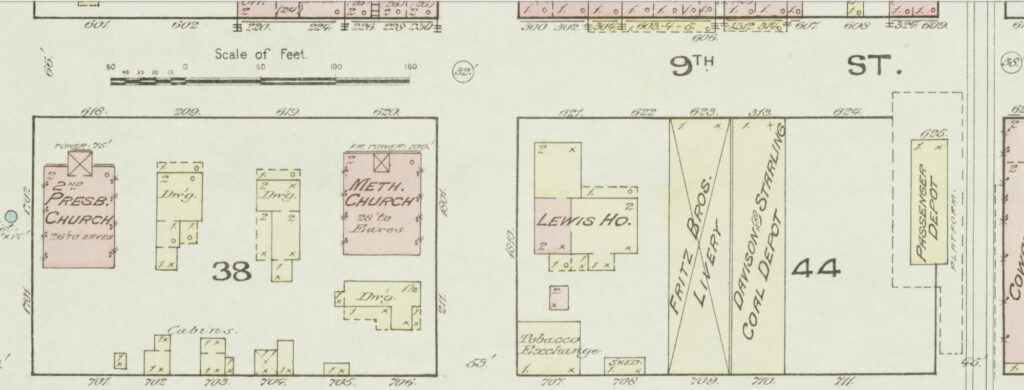

No known photographs exist, but the house does show up on the 1886 Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps of Hopkinsville. By 1886, the name of the business had changed to the Lewis House. Honestly, I am making an educated assumption that the floorplan of the house is similar to how it would have been in 1859-1860 when this ledger was used.

The house stood on the southeast corner of Ninth and Clay streets, where the HWEA offices stand today.

Based on its representation on the Sanborn map, the building appears to have been constructed in phases. I came to this conclusion because of the different building materials used. Standing two stories tall, the southwest portion of the house was brick — shown on the map in pink — while the north section toward Ninth Street and the extension to the east were frame or wood — indicated in yellow. A one-story section stood behind the wooden part of the house, and a series of one-story porches faced both north and south. A two-story brick structure stood behind the house. This small detached building may have been a kitchen house, or a stable or separate living quarters. There really is no way to know based on the information available.

But what we do know is that this was a large house with enough space to provide accommodations for travelers to this community.

“Bed, board, and hearth” were the mainstays of the common-law duties accepted by all innkeepers. The “bed” accounted for the sleeping accommodations; the “board” provided for food and other refreshments including alcohol; and the “hearth” was metaphorical in the sense that guests were guaranteed a sense of safety for themselves and their property during their stay.

Based on the contents of the Ritter House ledger, some guests stayed one night. Some stayed for weeks. Many were returning customers. But all appear to have received bed, board and hearth while they were there.

Archiving travels

This ledger provides an overwhelming amount of information about what everyday life must have been like in the mid-19th century — especially for one who was traveling.

The house itself stood in a prime location on a main thoroughfare. Our ledger dates a decade before a railroad came through Hopkinsville in 1868. The only way in and out of town were on horseback or in a buggy or carriage, and the Ritter House served as a stop along stagecoach routes.

Hopkinsville sat along stagecoach routes — or lines -— that connected us to Bowling Green, Clarksville, Nashville, Henderson and beyond.

According to an article in Middle Tennessee Genealogy, an average stagecoach traveled about 5-6 mph, with teams changing every 10 to 12 miles or so.

Stopping multiple times, many stagecoaches covered up to 70 miles in a day. Travelers typically paid 10 to 15 cents per mile traveled. The Stagecoach Inn in Guthrie (Todd County) and the Beckley Jackson House near Hanson (Hopkins County) stand as nearby reminders of this mode of travel that connected communities large and small.

Stagecoaches often carried mail and brought outside news to small towns along the way. Christian County Historian William T. Turner shared with me that a well-known stage driver named Ed Hockersmith was always a welcome sight when he arrived in town. He came along today’s Highway 68, and he would blow a horn as he crested Belmont Hill. Folks would flock to him to hear the news — and I’m sure to see the people whom he brought with him.

Hockersmith shows up in our ledger once in 1859. He was charged 75 cents for supper and lodging. The ledger includes the names of six other men listed as “drivers” who had accounts at the Ritter House, and the 1860 census gives us at least three additional names. Their job involved long, often bumpy hours, but they provided the only means of mass land travel to and from Hopkinsville for the first 70 or so years of our history.

A snapshot of the time

One of the first pages of our ledger is titled “Improvements” and shows more than $400 worth of work that Ritter invested in the property in early 1859. New paint, door latches, windows and repair to brick were all completed. “Furnishings (for Hotel)” also made the ledger — with absolutely no details other than a total cost of $4,540.35. All told, Ritter improved the property by almost $5,000 — or approximately $183,000 today.

I have pored over the pages of this ledger in an attempt to determine the cost of basic services at the Ritter House from 1859-1860. With some variations for special circumstances, lodging was a dollar per night, with dinner costing 50 cents per meal. One entry of “lodging with extra attention” for Phillip Bartlett cost him $5 per week for a seven-week stay. My best deduction is that it cost 70 cents per day for a horse to be kept and fed. One could rent a horse and buggy for $2, with the addition of a driver costing another $2. Stage fare from Canton was $2.50. Cigars were 5 cents each, and clothes were washed for about 10 cents per piece. And I found more than one “Bill for Lady” for a whopping $1 in the ledger. I think we all know what that means …

Payments were made to the Ritters in cash and trade. A number of people worked off portions of their bills or paid in goods — like turnips and sweet potatoes. A trip to the courthouse to look through deeds even turned up a tent or pavilion complete with ropes, seats and paintings that was sold to Ritter for $1 to pay off debt for board and lodging. A tent!

Our ledger continues through 1860 before making a big jump to entries dated to 1869-1872. These later entries reflect work being done presumably at Ritter’s farm. I was unable to determine when Ritter stopped his boarding house business at Ninth and Clay streets. The business continued under different management until the house burned in 1888.

This ledger has proven to be a treasure trove of information about our people and their habits in the days leading up to the Civil War. From how they traveled to how they found community in new places, our dusty, old ledger shows us how people found bed, board and hearth when they were away from their homes.

And I haven’t even gotten started on Burwell Clark Ritter, his family and all of the people who stayed at his boarding house — including the stagecoach drivers! Those stories, my friends, deserve to be developed in full. Stay tuned for part two about the Ritter House Ledger in May.

Alissa Keller is the executive director of the Museums of Historic Hopkinsville-Christian County. She’s a graduate of Centre College with degrees in history and English and of Clemson University/College of Charleston with a master’s degree in historic preservation. She serves on the Kentucky Historical Society and the Kentucky Museum and Heritage Alliance boards.