LOUISVILLE — When James Sweasy was 19 years old, he was convicted of a felony related to marijuana and spent the next 20 years of his life held back by his record.

He got a lawyer and started the “multi-months” process of expungement when he was in his early 40s, he said.

“No taxation without representation. … I can’t go on my kid’s field trip, right?” he remembers thinking. “I can’t elect a school board member that’s overseeing my kid? I don’t get a voice in that, but you’ll happily take my tax money? I didn’t like that.”

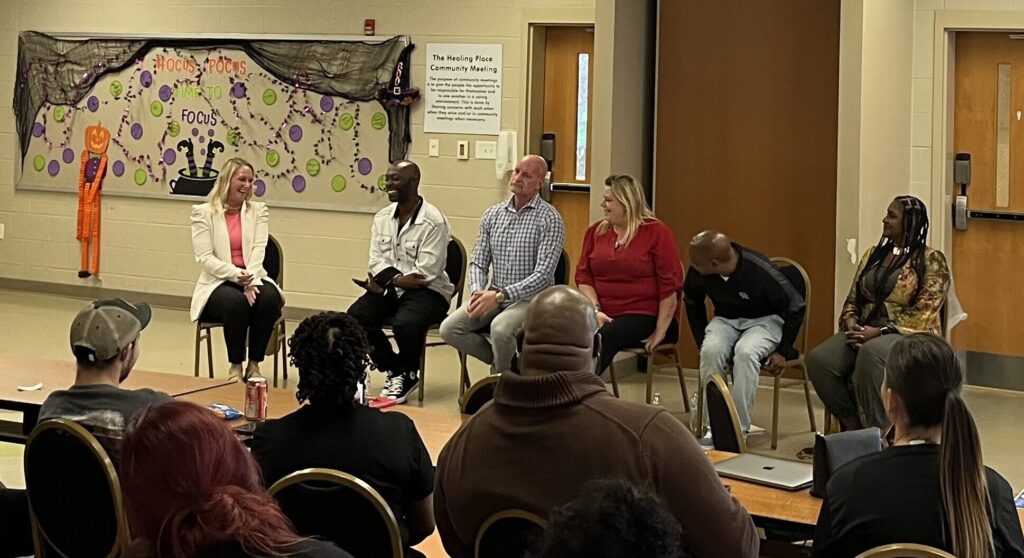

Sweasy was part of a five-person panel who spent nearly an hour Tuesday night at the Women’s Healing Place in West Louisville discussing Kentucky’s current process for crime expungement — and their proposal to ease and automate that process, which is expected to come before the legislature next year.

“The computer would notice that (a crime) is now eligible (for expungement) and start the process and move the process forward” without a person having to file a petition or hire a lawyer, explained Kungu Njuguna, a policy strategist with the American Civil Liberties Union of Kentucky.

In 2024, a slate of bipartisan lawmakers sponsored the proposal as House Bill 569, but it failed to advance past the committee stage. It’s unclear who would sponsor an automatic expungement bill next year.

In Kentucky, about 572,000 people are eligible to have their records fully cleared, according to data from The Clean Slate Initiative. But not everyone has the means and know-how to hire a lawyer, apply for expungement and ultimately clear their records, advocates said.

Sweasy called Kentucky’s current expungement system “archaic” and a “nightmare” full of “bureaucratic red tape” that was “not cheap.”

Njuguna said the proposed legislation would automate the current “complex” and “expensive” expungement process.

Crimes currently eligible for expungement would go through that process paperless and automatically. The proposal does not expand eligibility for expungement, Njuguna said, and only covers Kentucky crimes. Sexual and other violent crimes would not be eligible for automatic expungement.

“The current expungement process is complex, costly,” said Njuguna. “If you don’t have a lawyer, you probably aren’t going to get it figured out.”

This can hold Kentuckians back, he said, because many employers are reluctant to hire people who have been convicted of crimes.

“Having a criminal history prevents people from getting back into the workforce,” Njuguna said. “And so we’re trying to even that floor and give people clean records, get people back into the workforce to be able to reclaim their lives.”

This article is republished under a Creative Commons license from Kentucky Lantern, which is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Kentucky Lantern maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Jamie Lucke for questions: info@kentuckylantern.com. Follow Kentucky Lantern on Facebook and Twitter.

Sarah Ladd is a Louisville-based journalist and Kentuckian. She has covered everything from crime to higher education. In 2020, she started reporting on the COVID-19 pandemic and has covered health ever since.