LOUISVILLE — A leader of a national real estate research firm says if no action is taken over the next five years on Kentucky’s housing shortage, more Kentuckians could be forced to live in substandard housing, live with family or friends in crowded spaces, deal with severe housing costs or become homeless.

Patrick Bowen, the president of Ohio-based Bowen National Research which conducts housing market research across the country, presented findings Wednesday at an affordable housing conference. Bowen’s report is part of a housing gap study commissioned by the Kentucky Housing Corp., the state’s independent public corporation that invests in housing projects. It compared Kentucky’s current housing needs to projected needs in five years.

Kentucky currently needs about 206,000 housing units, including rentals and homes for sale. Without a push to build or repair more housing, that number is projected to increase by more than 80,000 by 2029 to 287,000-plus housing units, driven significantly by the need for lower-income rentals and higher-income homes for sale.

“It can be daunting. You can make it feel like the mountain is so high. How are you going to address this?” Bowen said. “But Kentucky, you’re not alone, right? This is a national crisis we’re going through.”

The estimate of housing needed takes into account what’s needed for a healthy housing market, to meet economic growth and to move Kentuckians out of poor-quality housing or from under severe housing cost burdens, meaning they pay 50% or more of their income on housing.

“If you care about the economy, care about jobs, when people spend over 50% of their income towards their housing costs, they’re not spending — they don’t have disposable income,” Bowen said.

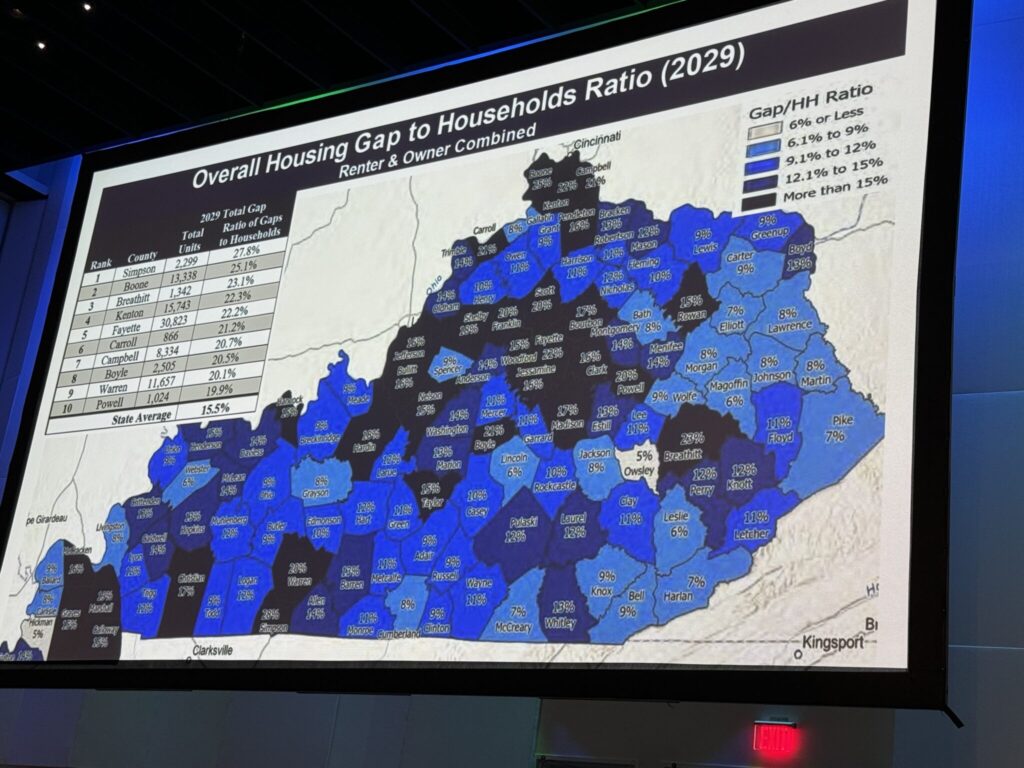

Bowen said while the highest need is in the state’s largest population centers of Louisville, Lexington and Northern Kentucky, rural counties could face a similar housing supply crunch by 2029. The consultant presented a map showing the number of housing units needed in each county as a percentage of the overall number of housing units in the county.

By 2029, the study projected the housing gap in numerous rural counties will rise to more than 18% of their existing housing units. Simpson, Breathitt, Boyle and Carroll counties would all have a housing gap to existing households of more than 20%. Bowen said Carroll County is projected to need only 866 housing units by 2029, but proportionally the county is “feeling this impact of the housing gap” just as much as other counties.

“Employers are feeling it, the citizens are feeling it, and it’s true for these bigger parts of the state, but rural Kentucky shouldn’t be forgotten,” Bowen told the audience.

The increasing housing gap for low-income Kentuckians, particularly renters, is projected to substantially worsen across the state. The number of rental housing units needed in each county as a percentage of the county’s total existing rental housing units is expected to be more than 30% in nine counties by 2029 including Franklin, Breathitt, Powell, Boone and Boyle counties. The rental housing gap in Simpson County is projected to be 46.5% of its total rental housing stock by that year.

Bowen’s firm found rental housing demand rising across all income levels but most significantly among households earning at or below 30% of an area’s median income. The gap in rental units, the study detailed, was equally driven by the growth in number of households along with those living under severe housing costs.

Bowen told the Lantern that while more housing units need to be built in Kentucky, other solutions such as weatherizing and repairing existing homes or providing financial assistance to those facing severe housing costs could help reduce the housing gap as well. He said encouraging housing developments of all kinds, especially affordable housing, is key.

“I think there should be a broad plan that allows people to stay in their homes if that’s what they want to do,” Bowen said.

The state’s housing gap, if left unchecked, could worsen the living situations of many Kentuckians, Bowen said. More people could be forced to move into living spaces with family and could be facing severe housing costs.

“Some of these people are going to become homeless,” Bowen told the Lantern.

Wendy Smith, deputy executive director of the Kentucky Housing Corporation, said the second phase of the corporation’s housing gap analysis should be made publicly available in September. Smith recently presented the first phase of the corporation’s analysis before a task force of lawmakers.

This article is republished under a Creative Commons license from Kentucky Lantern, which is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Kentucky Lantern maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Jamie Lucke for questions: info@kentuckylantern.com. Follow Kentucky Lantern on Facebook and Twitter.

Liam Niemeyer covers government and policy in Kentucky and its impacts throughout the Commonwealth for the Kentucky Lantern. He most recently spent four years reporting award-winning stories for WKMS Public Radio in Murray.