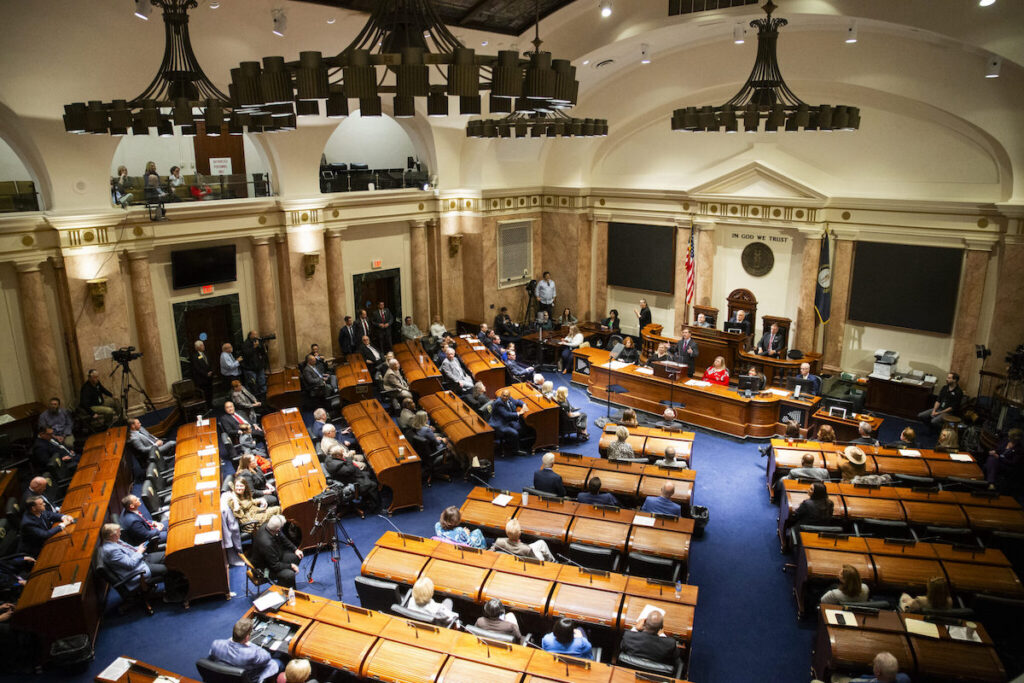

FRANKFORT, Ky. — Republican lawmakers say a flurry of bills to limit the governor’s authority would give more power to Kentuckians. However, Democratic Gov. Andy Beshear chalks up the trend to partisan “games.”

While the power struggle between Kentucky’s legislative and executive branches is nothing new, it’s become a recurring theme since voters elected a Democratic governor in 2019 — just three years after giving Republicans complete control of the General Assembly.

In this session, lawmakers are trying to flex control over everything from when they can meet in special session to decisions about permanent displays in the Capitol Rotunda.

Kentucky voters in 2022 rejected allowing lawmakers to call themselves into special session, a power now held exclusively by the governor. Republicans are trying again this year with House Bill 4 which the sponsor, House Speaker David Osborne, says would put a similar, but simpler, amendment on the ballot in November.

Also moving is Senate Bill 8, which would put new limits on the executive branch by allowing voters to decide membership of the Kentucky Board of Education. Now the governor appoints members who are confirmed by the Senate. The elections would be partisan. The move comes on the heels of the legislature enacting a law last year — over Beshear’s futile veto — that gives the Senate power over the state education commissioner’s confirmation and contract renewal.

Tensions between GOP lawmakers and the Democratic governor were heightened almost from the beginning of Beshear’s first term by COVID-19. In 2021, the Kentucky Supreme Court handed Beshear a defeat, upholding GOP-backed laws to limit the governor’s emergency powers. Beshear had challenged the laws arguing they undermined his ability to respond to the public health crisis.

Additionally, the Republican supermajorities put Beshear in a tough spot to push back because they can override any veto he issues.

Beshear, who was reelected in November, told reporters in his Thursday press conference that he views the moves to limit gubernatorial power at the start of his second term as an example of partisanship in Frankfort.

‘The back and forth’

Asked about pending bills curbing gubernatorial authority, Beshear hypothesized that Republicans would likely return the power they’ve taken away from him if a Republican is elected governor.

“People are exhausted about the back and forth,” the governor said. “And think about it, I mean, they’re focused on who has what powers instead of the jobs that people are going to or the quality of the roads or bridges that they’re traveling over. We could spend this time talking about public safety, public education. It’s time that they stop with the games and the partisanship, and focus on what’s most important for the people.”

However, Republican lawmakers argue that while their bills may restrict governor powers, they are putting more power in the hands of Kentuckians.

When asked if this year’s bills would have been filed if the governor was not a Democrat, Republican Senate President Robert Stivers, of Manchester, pointed to legislation he sponsored in 2017 to ease years of turmoil at the University of Louisville that had been aggravated by interference from Republican Gov. Matt Bevin.

Stiver’s law changed how board trustees at U of L are appointed. “If it’s there and we believe it to be bad policy or being abused in authority or power, we can do that,” Stivers said. “And have done it to Republicans and Democrats.”

But Bob Heleringer, a former Republican member of the House from Louisville, predicted that when a Republican returns to the Governor’s Mansion, a lot of the powers taken away during the Beshear administration will be restored.

The agendas of Republican lawmakers and Beshear are “very different,” Heleringer said. Also, Beshear is in office year-round while legislators are in session between 30 to 60 days a year.

Heleringer said his election to the House in 1979 came at the dawn of legislative independence in Kentucky. Before then, the governor dictated policy to the General Assembly.

When Gov. John Y. Brown Jr. won office in 1979, he did not get involved in the election of legislative leaders. Years later In 1992, voters approved amendments to the Kentucky Constitution that allowed governors to succeed themselves for a second term and changed the role of lieutenant governor, who previously could cast tie breaking votes in the Senate.

Now, the legislature is likely taking on an “enhanced role” because it’s controlled by a party different from the governor’s, Heleringer said. Republicans gained control of the Senate in 2000 and the House in 2016.

“They’ve gone from that to where the legislature is almost become the preeminent branch of government,” he said. “They have the numbers to do what they want from a partisan standpoint.”

People have also speculated that Beshear could run for higher office, even president. Heleringer said that is also an incentive for Republicans to not “l et him have accomplishments that he can brag about in some future race.”

‘Giving power to the people’

Stephen Voss, a political science professor at the University of Kentucky, said historically the state legislature has been weaker than the executive branch but over time has gained more power. The growing independence of the General Assembly has been a slow shift over the last century, making it a more co-equal branch of government with the executive branch.

The current Kentucky Constitution was adopted in 1891 during the Progressive Era. At the time, a lot of states were gutting legislative power and gave executive branches more authority over the lawmakers.

By the late 20th Century, Kentucky had relatively strong governors, who could call special sessions and set the topics for them, Voss said. Governors could also influence policy before lawmakers returned to Frankfort.

Democrats were also in power throughout that time. Republicans later took control of the Senate in 2000 and the House in 2016.

However, governors of the same party as the legislature have had power struggles with lawmakers. For example, Gov. Wallace Wilkinson, a Democrat, unsuccessfully sought support from lawmakers on constitutional amendments to allow state office holders to succeed themselves in office. (The amendment succeeded only after Gov. Brereton Jones agreed that it did not have to apply to him.)

“It’s no surprise that as soon as we had a legislative branch with distinctly different policy preferences than the governor, that the legislature has tried to claw back some of the power that it didn’t have compared to the balance we see in other states,” Voss said.

On the legislature returning powers if a Republican becomes governor in the future, Voss said “political institutions rarely give up power once they’ve gotten it.”

Separation of powers is “a matter of perspective,” Stivers said.

The state Constitution enumerates certain powers to the governor and the rest is “prescribed by law,” which is made by the General Assembly. Stivers gave the example that the Transportation Cabinet is not written in the Constitution, but the legislature created it.

Bills like the one to create partisan elections for the Kentucky Board of Education allow Kentucky voters to have a voice in the process rather than “having one type of autonomous functioning person making the appointments,” Stivers said.

“Actually, we’re giving power to the people, allowing them to vote on it,” he said. “And that’s what we think would be an appropriate thing.”

House Republican Floor Leader Steven Rudy, of Paducah, made similar comments while speaking to reporters about his bill to change how Kentucky’s U.S. Senate vacancies are filled. He said the U.S. Constitution gives the legislative branch the power to decide how to temporarily fill vacancies in federal offices.

“We’re not taking power from the governor and giving it to the legislature,” Rudy said. “If anything we’re giving it to the people.”

Earlier this week, the day after U.S. Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell announced he will step down from that role later this year, a committee unanimously approved House Bill 622 which limits the governor’s role in filling any Senate vacancies. The General Assembly had already changed the process in 2021, with McConnell’s backing, to ensure that Beshear couldn’t appoint a Democrat if a vacancy occurred.

When asked about HB 622, Beshear said governors of both parties before 2021 had the same “type of authority that they’re trying to tear away from me in my time as governor.”

“We want good government that focuses on our people, and think about how much time they’re going to spend debating it,” Beshear said. “How about we talk about expansion of health care and important needs that people have and not try to change this for the second time in two years?”

On Friday morning, the House passed a bill to give the General Assembly control over permanent displays in the Capitol Rotunda, rather than the governor’s appointees on the Historic Properties Advisory Commission. Beshear successfully urged the group to remove a statue of Confederate President Jefferson Davis from the area in 2020.

Meanwhile, Bevin, the one-term Republican governor, is still inspiring lawmakers to curb gubernatorial powers. The Senate this session has passed a bill with bipartisan support aimed at limiting governors’ pardon and sentence commutation powers around elections. The primary sponsor, Sen. Chris McDaniel, R-Ryland Heights, has repeatedly said his legislation was in response the controversial pardons issued by Bevin after his defeat, including to convicted rapists, murderers and child abusers.

“It adds democratic accountability to the use of an important check that the executive has on the judicial branch,” said Sen. Cassie Chambers Armstrong, D-Louisville, while voting in favor of the bill.

This article is republished under a Creative Commons license from Kentucky Lantern, which is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Kentucky Lantern maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Jamie Lucke for questions: info@kentuckylantern.com. Follow Kentucky Lantern on Facebook and Twitter.