As an attorney and Army veteran, I have experience talking to people about painful things, from sexual assault to end of life planning to murder. Unfortunately, this is a time when I need to say something uncomfortable. You may remember last year I wrote a letter to the editor about not letting misinformation and divisiveness lead to violence. I couldn’t leave it unsaid then and I can’t now.

On Jan. 6, we were at grave risk of losing our democracy to political violence. We want to move on and assume things are fine now, but things aren’t fine. We’re still at risk.

I’ve studied political violence for years, from graduate school and law school to service in the military. One of my first memories of political violence is learning of the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995 as an Oklahoma elementary school student.

In law school I participated in national security conferences in Washington, D.C. and New York as I prepared to start my active duty time in the Army. I spent two years as a legal intern with the Fort Hood shooting prosecution team, who worked to convict Nidal Hasan of 13 counts of premeditated murder and 32 counts of attempted premeditated murder for his Nov. 5, 2009, attack. I can still see the Fort Hood crime scene in my mind and hear a survivor relay the dying words of one of the fallen: “Tell my family I love them.”

I was at Fort Hood when Naser Abdo came to Texas to bomb soldiers near the base as a sort of copycat attack in 2011. We stayed safe in part because the nearby gun shop he went to, Guns Galore, had been frequented by Nidal Hasan, and the store clerk reported Abdo’s suspicious behavior. Police found bomb making supplies and instructions in his hotel room along with other weaponry. I sometimes wonder where I’d be if the clerk hadn’t spoken up in time for the police to stop Abdo’s Fort Hood attack.

- JOIN THE CONVERSATION: How to submit a letter to the editor

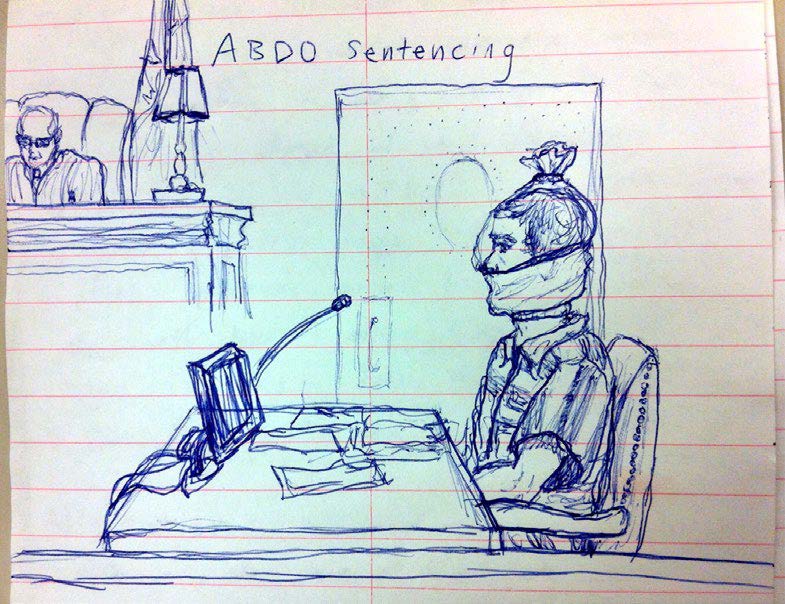

I attended Abdo’s sentencing for the planned attack in 2012 in the federal court in Waco, Texas. He showed no remorse. I even sketched this drawing of the covering he had to wear in court because he claimed to have infected himself with HIV to spit on the guards.

Later on active duty overseas I ran with coworkers into concrete bunkers to the sounds of “incoming” blaring over loudspeakers, warning us of indirect fire attacks on our base. Afterward, we’d brush ourselves off and emerge from the bunker, grateful that we weren’t in the impact zone and wondering about the others on base. Even as we dusted ourselves off, we always knew that there could be another attack and the next one could be worse.

Watching the recent C-SPAN coverage of the Jan. 6 hearings, that post-attack mix of relief and expectation is the feeling I have for our country. Most of us weren’t in the direct impact zone of the most recent attack, and we’re going on with our lives. But we need to recognize that it’s not over. If we don’t pay attention and get involved on the side of nonviolence in politics, the next one could be worse. If we don’t learn from the last one and speak up about what’s going on, it could be your workplace next time. Believe me.

There is no place for political violence in the United States of America, not from any side or for any reason.

It’s time to say out loud that folks who encourage or excuse political violence like the January 6th attack are flat wrong. It’s not something to wink away with a smirk, as though hurting and killing are no big deal. Imagine if the Guns Galore clerk had just looked the other way when Abdo came in the store and ignored the red flags instead of calling police. Speaking up saved lives then and it can now.

Please think of your friends, family, and neighbors. Look at your kids. Don’t lose them to the next wave of homegrown political violence, whether as collateral damage, as targets, or from getting pulled into a social group that perpetrates it.

The risk of our acquaintances and loved ones being recruited to commit political violence against the government or fellow Americans is real and it’s here, whether we want to talk about it or not.

The path to violent action sometimes starts with normalizing talk of violence and glorifying symbols of violence. Think about what you might say or do if you encounter those early steps.

If you see something, please say something. You can save lives.

Sarah Brechwald is now a civilian attorney in Hopkinsville. Before serving as a Judge Advocate General Corps officer with the 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) from 2014-18, she earned a master’s degree in International Relations from Troy University in Troy, Alabama and a Juris Doctor from the University of Texas School of Law in Austin, Texas.

Sarah Brechwald is an attorney in Hopkinsville. Before serving as a Judge Advocate General Corps officer with the 101stAirborne Division (Air Assault) from 2014-18, she earned a Master’s Degree in International Relations from Troy University in Troy, Alabama and a Juris Doctor from the University of Texas School of Law in Austin, Texas.