President Abraham Lincoln instituted the celebration of Thanksgiving as a national holiday in 1863 after the Union victory at the battle of Gettysburg, during the American Civil War. It was not a new idea – in 1789, President George Washington had proposed a yearly presidential proclamation of each annual Thanksgiving holiday, but President Thomas Jefferson refused to issue one after he was elected, as he considered it a religious event. Later presidents followed his example, and the holiday was effectively discontinued on the national level until Lincoln’s declaration.

Today, Thanksgiving Day has come to be celebrated every year on the fourth Thursday of November. As a specialist in Catholic history and worship, I am aware that behind the history and legend of the first Thanksgiving lies a rich story that illuminates the medieval Christian roots of the holiday.

Medieval Catholic liturgy

Since the beginning of Christianity, the Eucharist, also called Holy Communion or the Lord’s Supper, has been the primary worship service for Christians all over the world. The name itself comes from the ancient Greek word for thanksgiving, “eucharistia,” although in part of the New Testament it is also called “the breaking of bread.”

The service came to be called the Mass in Western Europe, derived from the Latin dismissal rite at the conclusion of the ceremony: Ite missa est – “Go, it is the dismissal.” The term is still used by Roman Catholics today.

One of the most important medieval Catholic rituals, the Eucharist involves a special blessing, called a consecration, of bread and wine. This consecration is rooted in what Jesus Christ did during the ritual meal he shared with his apostles before his arrest and crucifixion – the Last Supper. The ritual as a whole is a thanksgiving to God for the offer of salvation from sin in the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus Christ. From at least the fourth century, Christians were expected to attend Mass every Sunday, with a few exceptions, and to rest from work.

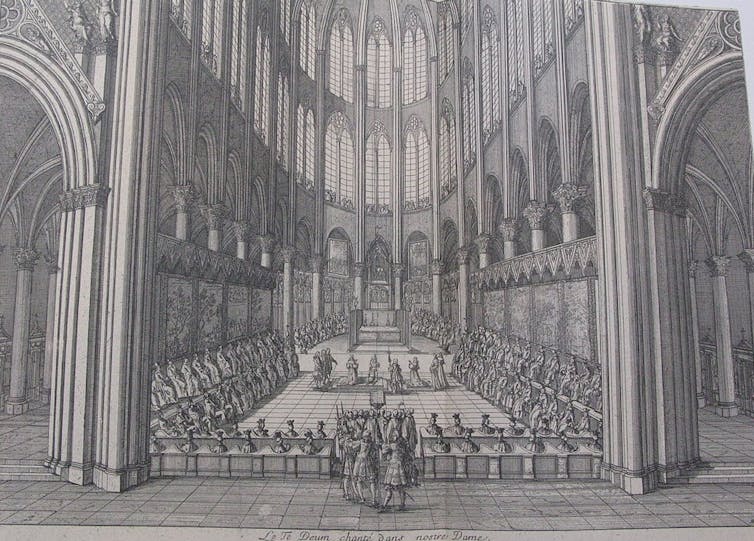

But Catholics expressed thanksgiving in other ways, too. One hymn’s first line, “Te deum” – which says, “You, God, we praise” – has been used for centuries in Catholic worship, frequently on occasions calling for celebration and thanksgiving.

Legend has it that the text was composed by St. Ambrose, a famous theologian and Doctor of the Church. It is sometimes referred to as the “Ambrosian hymn” in medieval sources.

An early reference to the hymn is in a sixth-century book, “The Rule of St. Benedict,” a collection of regulations for monks and nuns. It is listed as one of the prayers to be recited or sung at Matins, their daily morning communal prayer service.

The Te Deum was often followed by another short hymn: “Non nobis Domine.” Taken from the first line of Psalm 115, “Not to us, Lord, not to us but to your name give glory,” it is another brief expression of thanksgiving to God for whatever event was being celebrated.

Catholics sang the Te Deum as a private or public way to offer thanks to God in a number of situations for centuries. King Philip II of Spain, a devout Catholic, ordered it sung after hearing of the victory of a Catholic fleet against the Ottoman Turks at sea off the shore of Greece. This Battle of Lepanto in 1571 stopped a Muslim advance into Catholic Europe.

Historical English thanksgiving

Medieval England was a Catholic country, and the public religious rituals celebrated in churches were much the same as those celebrated in Rome and the rest of Catholic Europe, with some local differences. Many of these rituals involved the theme of giving thanks.

In addition, the practice of blessing people, animals or crops was also an important part of medieval Catholic liturgy. Many of these blessing prayers included the theme of thanksgiving as well. One set of blessing prayers dealt with the blessing of ordinary bread.

Across Catholic Europe, bread might be blessed on certain feast days, but in the British Isles, a special ceremony would take place on August 1, when the first of the wheat crop was harvested. This date was called Lammas Day, from the Anglo-Saxon words for “loaf” and “Mass.” From at least the ninth century on, bread from these first grains would be baked into intricate shapes and brought to church for a special blessing.

However, this blessing of the first loaves only marked the beginning of the harvest. It was also customary in England, as well as in other parts of Europe, to hold a public festival when the harvest was done, the “gathering-in” or “harvest home.” Dancing, eating, drinking and other forms of entertainment were featured. This was originally a secular festival, although other festivals of this kind could also be held on other occasions, like weddings.

Public liturgies of thanksgiving could also be proclaimed on other occasions. For example, the English victory over the French at the battle of Agincourt in 1415 was celebrated in London by the mayor and populace with the singing of the Te Deum and the ringing of bells at the city’s churches. Later, a prayer service in Westminster Abbey was held, attended by the mayor and members of the royal family.

The Church of England

After King Henry VIII broke away from Rome in 1534, the English sovereign became by law the Head of the Church in England. After his death, a reformed English-language liturgy, compiled in the Anglican Book of Common Prayer, was used throughout the country.

Public worship services of thanksgiving were held annually on certain specific occasions, like the anniversary of the sovereign’s accession to the throne. As in the medieval period, the sovereign could also proclaim a day of thanksgiving, complete with the singing of the Te Deum in Latin, to celebrate other important events, like the birth of a royal heir – in this case, the birth of Prince Edward, the future King Edward VI, to King Henry VIII and his third wife, Jane Seymour, in 1537. King James I was the first King of England to be crowned in an English-language ceremony.

Protestant Pilgrims

However, not every Christian in England was happy with the Book of Common Prayer, finding it still too influenced by Catholic practice. The Pilgrims were among the English Protestant groups who rejected the Church of England’s more moderate reforms completely and wished to separate from it to form their own church communities – separatists – as opposed to the Puritans, who desired further reforms within the Church of England to “purify” it.

Because of increasing legal persecution of “non-conformists” – those who did not attend or belong to the Church of England – in the early 17th century, they at first left England for a country where they might practice their beliefs freely. In Holland, they settled in the town of Leiden, and lived there for several years. But the Pilgrims faced other problems there – they worked at low-paying jobs and they worried that their children were becoming more Dutch than English.

Eventually, they joined a group of other travelers on a ship called the Mayflower to travel to the New World. There, in 1620, they landed a little farther north than their original destination – Virginia – settling at Plymouth on the coast of what is today Massachusetts in December 1620.

The Pilgrims faced a hard struggle to survive that first winter and many died. But after a good harvest the next year, they celebrated. They may not have sung a Catholic or Anglican Te Deum or danced in the street, but they held a Thanksgiving in their own way following the customs they had grown up with in England: with prayer and feasting.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Joanne Pierce is a professor emerita in the Department of Religious Studies at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Mass. Her research interests include liturgical studies, medieval Christianity, ritual studies, ecumenical theology, theology and speculative/science fiction.