Hopkinsville native Ted Poston, who excelled as the first Black journalist to make a career at a white-owned metropolitan newspaper, has been selected for the Kentucky Writers Hall of Fame.

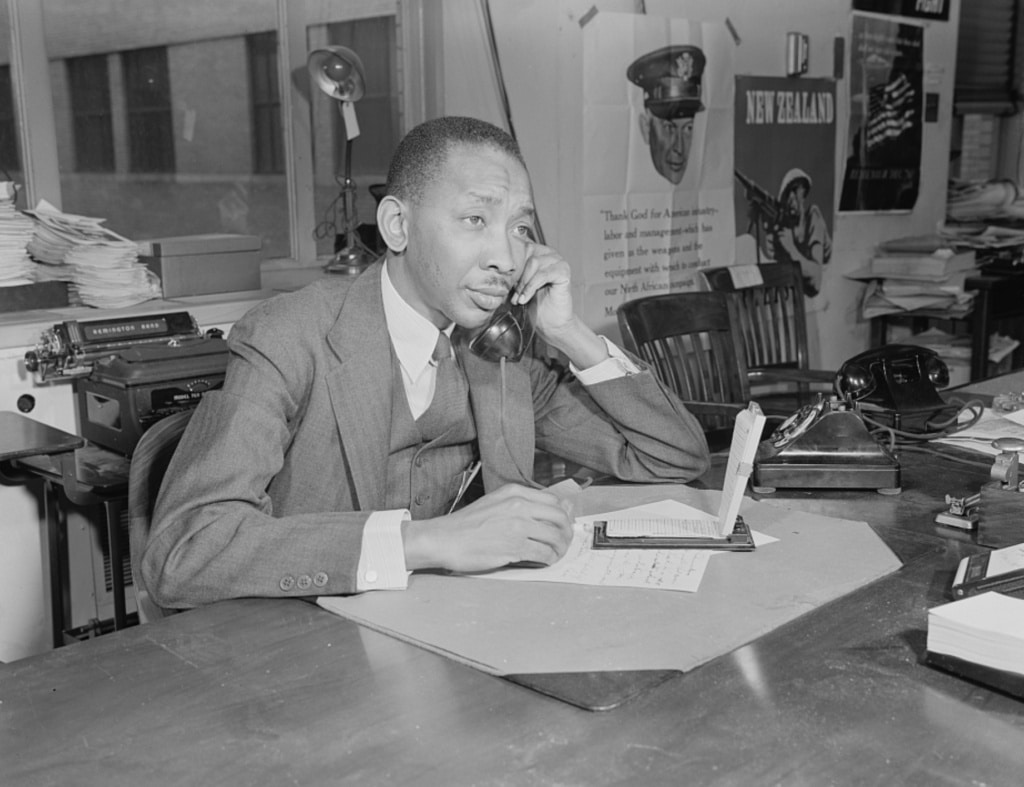

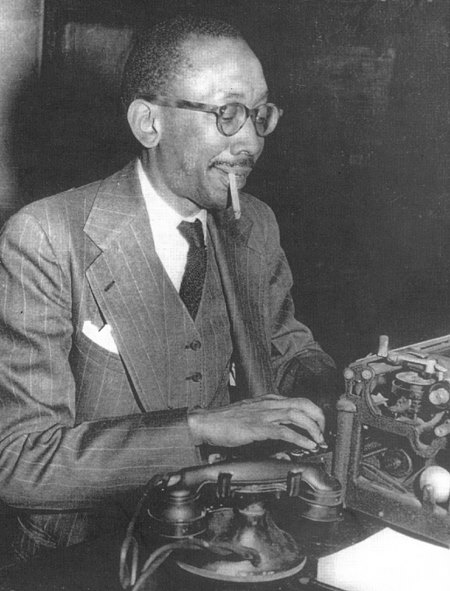

Recognized as the dean of Black journalists in America, Poston covered major stories on civil rights, politics and Black culture as a staff writer at the New York Post from the mid-1930s until his retirement in 1972. His stories earned several journalism awards and a Pulitzer Prize nomination.

Poston, who died in 1974, also wrote humorous, insightful short stories about growing up in segregated Hopkinsville during the 1910s. The collection was published posthumously as “The Dark Side of Hopkinsville.”

The Carnegie Center for Literacy and Learning in Lexington will induct Poston and four others — George Ella Lyons, James C. Klotter, Loyal Jones and the late Robert Hazel — in its 2022 Hall of Fame class. A ceremony is planned at 7 p.m. on March 24 at the Kentucky Theatre in Lexington, assuming COVID-19 infection rates decrease by then.

- OUR COVERAGE: Read more about Hopkinsville native Ted Poston

Poston will become the second Hopkinsville native in the Kentucky Writers Hall of Fame, joining Gloria Jean Watkins, the writer known by her pen name bell hooks. She was inducted in 2017. (Watkins died on Dec. 15 at her home in Berea.)

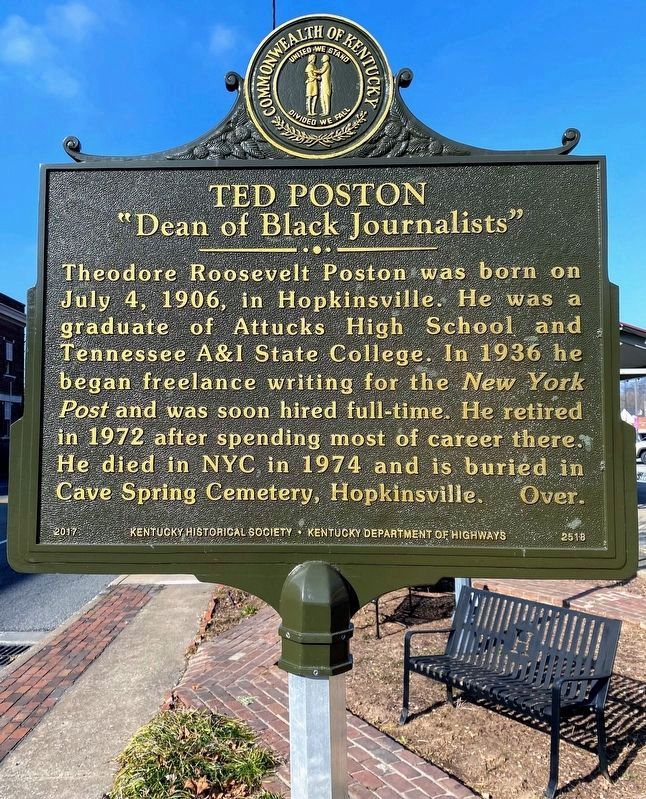

Born on July 4, 1906, Poston was the youngest of eight children. His parents, Ephraim and Molly Cox Poston, were educators who met at Roger Williams University, a teacher’s training school for Black students in Nashville. After they wed in 1887, they moved to Hopkinsville. Their home was on Hayes Street.

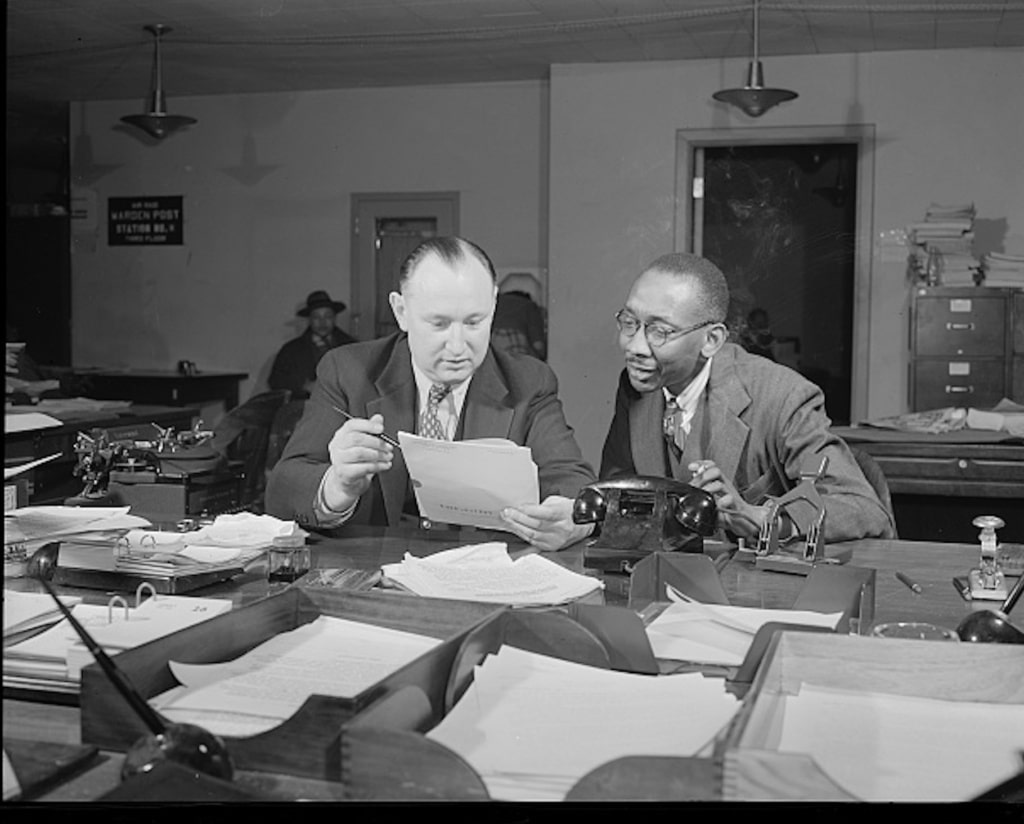

Ted Poston graduated from Attucks High School in 1924. He earned a bachelor’s degree from Tennessee Agricultural and Industrial College (now Tennessee State University) in Nashville in 1928 and began working for the New York Post newspaper as a freelancer in the mid-1930s. He soon became a staff writer. He left the paper just once, during World War II, to serve as the Negro News Desk chief in President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration.

‘A perfect fluke’

Poston “provided an insider’s view on segregation and the civil rights movement,” wrote his biographer, Kathleen Hauke. “His incisive, usually upbeat, sometimes acerbic reports on everyday racism were eye-openers for the paper’s mostly white readership.”

Poston once said he got his job at the New York Post “through a perfect fluke.”

Walter Lister, the city editor, agreed to pay Poston 30 cents an inch for news copy — if he could dig up an exclusive story for the front page. Poston met the challenge when he returned with a story about a man being attacked as he tried to serve court papers in Harlem.

Poston joked that it wasn’t long before he was writing so much copy as a freelancer that he could have made more money than the editor’s salary. Lister apparently had never intended to hire Poston full time but finally conceded, saying, “What the hell. I’m going to give you a job.”

Unique challenges

Poston faced many obstacles that white reporters never experienced. In the Jim Crow South, he often concealed his identity and profession by dressing as a laborer.

“I sat up there in the Negro gallery in ragged overalls pretending to be a country boy … and I would make notes under the overcoat on my lap,” he said, describing how he covered the trial of two black Alabama teenagers accused of raping a white woman in the 1930s.

Poston would hide his story on top of a partition separating the black and white restrooms in the courthouse, and a white reporter secretly picked it up and wired it to New York with his own copy.

After that trial ended, Poston was nearly discovered by a group of white youths who confronted him at the train station, Hauke wrote. Poston produced phony credentials identifying himself as a black preacher. It was a ruse that probably saved his life, he said.

Poston’s career also took him to the country’s major civil rights battles, from the bus boycott in Birmingham, Alabama, to the desegregation of schools in Little Rock, Arkansas.

When Poston asked for the assignment to cover the trial of three Black defendants charged with raping a young white woman in Lake County, Florida, his editors feared it was too risky for him. A few months before the trial, angry white mobs had menaced Black residents in the region, chasing them from their rural homes and into the orange groves of Lake County.

But not even Poston, who had experienced racism and threats first-hand, was prepared for what awaited him when he left the Lake County Courthouse after the defendants were found guilty and two of them were given death sentences. On a 40-mile stretch from Tavares to Orlando, Poston and three companions were terrorized by whites in several cars who joined the chase at strategic points along the highway.

Relating their escape, Poston wrote, “How does it feel to be chased down a lonely moonlit Florida road — in a small car careening from side to side at a 90 (mph) clip — and with sudden death facing you from a possible collision ahead or a bloodthirsty mob behind?”

Poston’s description of his flight from Lake County, along with evidence he uncovered that indicated the Black defendants were falsely accused and beaten by police, ran as part of a series called “Horror in the Sunny South.” Poston’s editors thought it was the best work in the newspaper that year and nominated him for a Pulitzer Prize.

The series did not win the Pulitzer, but it did earn other prestigious recognition, including the George Polk Award.

“Horror in the Sunny South” is ranked No. 89 on a list of the best American Journalism of the 20th century, released in 1999 by a panel of experts for the New York University School of Journalism.

In 2021, the state of Florida exonerated the defendants in the case that is widely known today as the Groveland Four case.

Blazing trails

Poston’s greatest contribution to journalism, Hauke wrote, was breaking barriers for future black writers.

Her biography, “Ted Poston: Pioneer American Journalist,” was published in 1998. She also edited a collection of his best journalism, “A First Draft of History,” published in 2000. The University of Georgia Press published both books and “The Dark Side of Hopkinsville” which Hauke also edited. She lived in Hopkinsville for several months in 1984 to research the Poston family and the characters in the short stories.

When “The Dark Side of Hopkinsville” was published in 1991, it marked the first time that many Hopkinsville residents learned about Ted Poston and his achievements.

Poston was inducted into the Kentucky Journalism Hall of Fame in 2000.

In 2017, the Kentucky Historical Society and local supporters dedicated a historical marker for Poston at Founders Square downtown. It was the first historical marker for a Black person in Christian County.

Poston died on Jan. 11, 1974, at home in New York City. He is buried at Cave Spring Cemetery in Hopkinsville.

(Editor’s note: Hoptown Chronicle editor Jennifer P. Brown nominated Ted Poston for the Kentucky Writers Hall of Fame. Brown also spearheaded the effort to install a historical marker in his name.)

The other four Kentucky Writers Hall of Fame inductees this year are:

George Ella Lyon, of Harlan, has published 10 collections of poetry and eight novels, including six for young readers. Her 1993 poem, “Where I’m From,” has become a classic writing prompt used by teachers worldwide. The poem was a prompt for a Hoptown Chronicle project, “Homegrown Poems: Your Places, Your Stories in Verse” in October 2019.

James C. Klotter, who grew up in Owsley County, has been Kentucky’s official state historian since 1980. He has written 12 books and more than 60 articles, and six other books include a chapter he wrote. He is a former executive director for the Kentucky Historical Society and he was a history professor at Georgetown College from 1998 until 2018.

Loyal Jones, a scholar of Appalachian culture, is the author or co-author of 13 books and dozens of articles. He’s been called the “father of modern Appalachian studies.” He led Berea College’s Appalachian Center, which is now named for him.

Robert Hazel, who taught writing at the University of Kentucky from 1955 to 1961, influenced many Kentucky writers, including five other Hall of Fame members — Wendell Berry, Bobbie Ann Mason, James Baker Hall, Ed McClanahan, Gurney Norman and James Baker Hall. He wrote five poetry collections, three novels and several short stories.

Jennifer P. Brown is co-founder, publisher and editor of Hoptown Chronicle. You can reach her at editor@hoptownchronicle.org. Brown was a reporter and editor at the Kentucky New Era, where she worked for 30 years. She is a co-chair of the national advisory board to the Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues, governing board past president for the Kentucky Historical Society, and co-founder of the Kentucky Open Government Coalition. She serves on the Hopkinsville History Foundation's board.