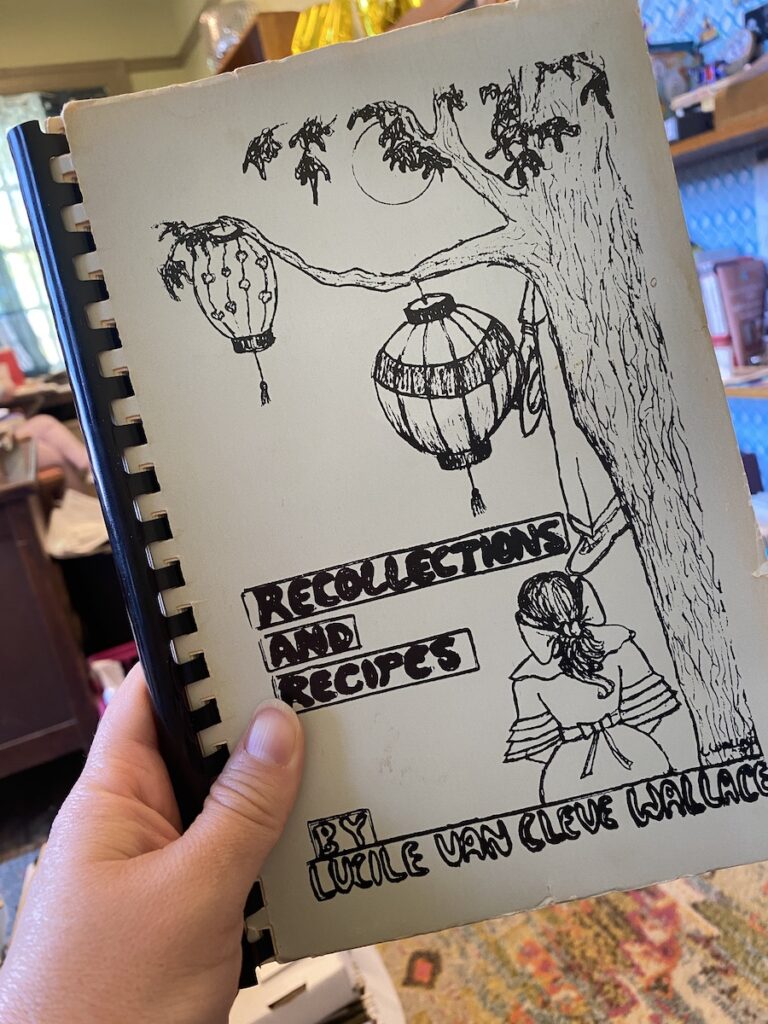

This unassuming book measures just over 6.5 inches wide and 9 inches long and is held together with plastic comb binding. It contains approximately 144 pages that are filled with life and memories and food. The cover is a faded, pale green and features a hand-drawn illustration of a young girl with a bow in her hair and around her waist. She sits beside a tree under the moonlight. Japanese lanterns decorate an overhanging branch above the book’s title and author, “Recollections and Recipes” by Lucile Van Cleve Wallace.

Our artifact this month is a cookbook.

Truth be told, I had no intention of writing about this cookbook this month — or ever. I didn’t even know that it was tucked away in the museum’s collection. But I went to a conference earlier this month where a dinner was prepared for us using recipes from an 1830s cookbook, and this experience that brought history alive through food truly fascinated me. The food was delicious, but the story and the process was even more.

What could we do here to build off that idea? Supper Club, that’s what! Every other month, the Museum partners with the Human Rights Commission to bring people together over food. For a year and a half, we have welcomed guest “chefs” from varying cultures and backgrounds to cook and share their traditions with us. And it has been amazing — every single time.

“Recollections and Recipes”

With the help of Sacra Fallen, our collections manager, I sought out cookbooks in our collection. I wanted to craft a meal for Supper Club using a local cookbook much like was done at this conference. This book stood out to me immediately. Published in 1978, this little book was written by Lucile Van Cleve Wallace. The title, “Recollections and Recipes,” indicated that it might be more than a cookbook. And it is.

Ruth Lucile Van Cleve was born in Christian County on Nov. 4, 1895, the daughter of John James ‘”J.J.” and Mary Ermine Corbin Van Cleve. The youngest of five children, Lucile grew up on a farm on Clarksville Pike (better known to us today as 41-A). In addition to regular crops, the Van Cleve’s also raised thoroughbred horses. The 1900 census lists the Van Cleve household as J.J. and Ermine, their five children, and Joseph E. McCown, a boarder who worked as a horse trainer.

The first 20 or so pages contain the recollections part of Lucile’s work. The six short chapters provide a glimpse into the life of a privileged farm family in Christian County at the turn of the 20th century. In its very “moonlight and magnolias” nostalgia, it gives a perspective that we don’t often find. These are the memories of a woman — her memories of girlhood. Chapters are titled “The Grange Sale,” “Christmas at Home,” “Hog ‘Killin’,” “Bread,” “Quail,” and “Moonlights” and Conclusion.” How charming!

Culinary inspiration

While these chapters introduced me to new stories, they were not my focus. My focus was on the recipes. Lucile explains in her final chapter that these recipes were gathered over her lifetime. After marrying William A. Wallace, she and her husband moved quite a bit for his work. They lived in St. Louis, Chicago, Houston, New Orleans, Birmingham, Kansas City and Florida — all before retiring to Hopkinsville in 1958. Her culinary inspirations in this small cookbook come from all of these places; however, it was mainly her mother’s influence that inspired me and the meal I made for Supper Club.

I also got a little help with my meal plan from the Kentucky New Era. When the “cook-book plus,” as she called it, first came out, the New Era ran a full-page feature on its food page. I chose recipes that Lucile shared with the newspaper.

The most intriguing and surprising recipe, in my opinion, is found in the “Cheers and Canapes” chapter. Its title is perfectly descriptive: Bacon and Peanut Butter Appetizer. Lucile credited the recipe to Ann Batchelder, a writer for the Ladies Home Journal. The recipe as given in the cookbook only has two ingredients: bacon and peanut butter. Slices of uncooked bacon are slathered with a thin layer of peanut butter, rolled up, secured with a toothpick, and baked in the oven at 400 degrees for about 20 minutes. A little trial and error with some friends encouraged me to add a bit of brown sugar to the concoction, and I cut my rolls in half to allow for a crispier finished product.

And boy! Were they yummy! Lucile described them as “different and delicious.” I totally agree.

I picked Brunswick Stew as our main course. This recipe was attributed to her mother and from her mother’s first cookbook “Common Sense” by Marion Holland. It was a seasonal recipe often prepared in late August or early September that used up the last of the year’s tomatoes, corn, butter or lima beans, and okra in the garden. The original recipe calls for two to three squirrels — as the stew was usually made during their hunting season. Lucile shared that chicken had replaced squirrel for the meat — making this recipe easier (and frankly, more palatable) for me to replicate.

Thanks to my mom’s willingness to help, she actually cooked the stew. She boiled a whole chicken in salted water — just enough to cover — and picked the meat from the bones when it was done. Parboiled potatoes, fresh corn (frozen last summer), frozen lima beans and okra were added to the stock to cook with a ham hock and other seasonings. A quart of tomatoes and the cooked chicken were added after the veggies were soft. Finally, the recipe called for a half pound of butter to be cut into bits the size of a walnut and rolled in flour. The stew cooked for 10 more minutes to finish.

This fairly simple dish was reminiscent of so many stews that come to mind. It served a dual purpose of making enough to feed a crowd while using what was on hand to make something delicious. The Supper Club crowd ate every bite!

But my favorite part of the night was dessert. Lucile featured her mother’s Jam Cake recipe in the Kentucky New Era article, so I thought it was the best one to try. Much like the Brunswick Stew, the cake was out of season for June. Jam Cake was a Christmas treat. Lucile described how her mother would make numerous cakes every year for the holidays. They employed an African American cook who provided the meals for the family and farm laborers, but her mother made desserts for special occasions. Lucile remembered that her mother always baked at night — when the house was quiet and she didn’t have to vie for space in the kitchen.

These cakes were made as gifts and for the family to have on hand for what she referred to as a “spend a day” affair with neighbors, friends and other company just dropping by to visit. This revelry lasted all through the Christmas week — which meant lots of cakes!

Somehow, I have no personal memory of eating or even seeing a jam cake, so this baking adventure was a first for me. The cookbook actually has two different recipes, but I chose to bake her mother’s version from about 1915. The cake itself was fairly straightforward and featured buttermilk and all of the spices that made it smell and taste like Christmas. Blackberry jam and raisins were folded in before it was baked. This recipe instructed that the cake be baked in two 9-inch pans.

Like all jam cakes, this one called for caramel icing. Despite my ultimate fear of burning it or producing a grainy mess, I managed to make this delectable topping in front of — and with encouragement from — the Supper Club crowd.

The most fun part of the jam cake (other than eating it) was the stories that it inspired. As I was making the icing, others shared how they make caramel icing themselves and the lessons that they’ve learned about it. Still others talked about the jam cakes that their mothers and grandmothers made and how it didn’t feel like Christmas until you had a piece of that dense, moist treasure. It even led me back to my own family recipes where I found my grandmother’s and my great-grandmother’s jam cake recipes. You know I’ll be making those for Christmas this year!

I think it would’ve made Lucile Van Cleve Wallace happy to know that her recollections and recipes inspired this meal, this article and this woman to bake a jam cake. She explained her desire to write this cookbook, saying, “My idea, though practical, had its sentimental side, too. I wanted the younger generation of the family to have them (the recipes) and hoped they would be interested in some of the incidents or descriptions associated with some of the recipes and information of ‘house-holding in the early 1900s and before.’”

We are interested — in these recipes and in the ones from our own families. And we are grateful that a Christian County woman took the time to share a bit of her life with us through her food.

Alissa Keller is the executive director of the Museums of Historic Hopkinsville-Christian County. She’s a graduate of Centre College with degrees in history and English and of Clemson University/College of Charleston with a master’s degree in historic preservation. She serves on the Kentucky Historical Society and the Kentucky Museum and Heritage Alliance boards.