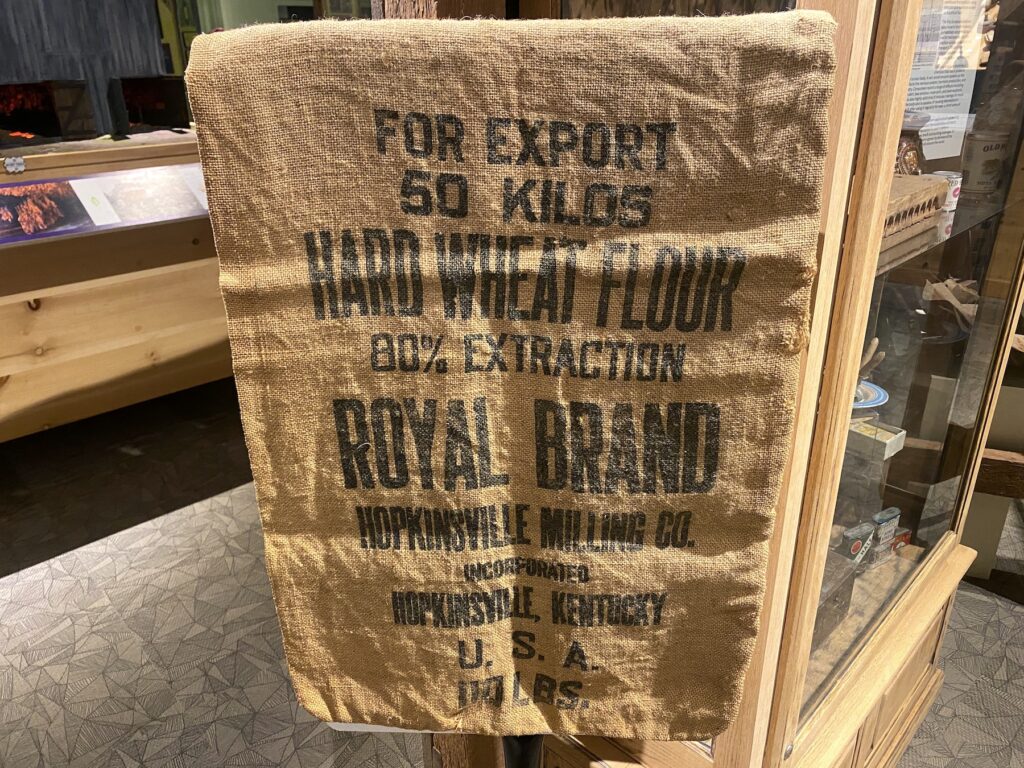

The large brown sack is made out of rough burlap and measures 37 ½ inches tall and 20 inches wide. The back of the bag features a small insignia for the Bemis Co. Inc., but only a trained eye could identify it. Printed on its front in bold, black lettering is the following:

FOR EXPORT

50 KILOS

HARD WHEAT FLOUR

80% EXTRACTION

ROYAL BRAND

HOPKINSVILLE MILLING CO. INCORPORATED

HOPKINSVILLE, KENTUCKY

U. S. A.

110 LBS.

Our featured artifact this month is a flour sack.

To be completely honest, this flour sack likely would have never caught my attention if it weren’t for a program that I did a few years ago. The Christian County Homemakers asked me to present on the history of mills and the milling industry in our county. Lucky for me, the group also asked Robert Harper, owner and president of Hopkinsville Milling Co., to talk about his mill and its specific operation.

This joint presentation was given during COVID days, so we joined with the homemakers on Zoom. As Robert shared about the mill, I scurried into the museum’s textile storage to retrieve a couple of flour sacks that we have in our collection. One of these sacks is much more what I think of when I think of a historic flour sack. It is absolutely beautiful. Packaged for the Royal Lily brand of self-rising flour, the sack features a gorgeous white lily. A stunning piece of marketing, for sure. If I was going to buy flour in a sack, I certainly would pick a pretty one.

Decorative flour sacks were an innovative advertising technique used by milling companies in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Up until the late 1800s, flour was stored and shipped in wooden barrels. Sewing machines made it possible for sturdy sacks to be made to hold flour. Fabric sacks were all the rage until World War II when paper bags became the main form of packaging.

Millers used these fabric sacks as a major form of advertising. Elaborate designs for different flour brands graced the sacks to catch the consumer’s eye. The fabric also proved to be quite the hot commodity with sacks being taken apart and repurposed as towels, rags, and even undergarments. During the Depression, milling companies began to produce sacks made specifically out of printed fabrics that could be recycled for use in clothing and quilts.

But what about our simple, straightforward burlap bag? Turns out, its story is even more interesting and connects us to a much larger, international narrative.

The key clue to its story is found printed right on the sack: 50 kilos. Why on Earth would a bag of flour made in Hopkinsville use a metric weight?

The simple answer is that this bag of flour was produced specifically for export to Europe. The more interesting detail is that it was produced specifically for export to Europe in 1949 as part of the European Recovery Program — better known as the Marshall Plan.

Named for U.S. Secretary of State General George C. Marshall, the Marshall Plan provided economic aid to 17 countries ravaged by war in western Europe. Major goals of the plan included rebuilding war-torn regions, removing trade barriers, modernizing industries, and improving European prosperity. An added intention was to prevent the spread of communism. From 1948 through 1951, the U.S. transferred more than $13 billion to aid in the recovery of the economies of countries in western Europe.

The Marshall Plan also provided a new and expanded market for many American exports – which is where our flour sack comes into play. With both agricultural production and industrial operations (like mills) in dire straits after the war, European countries were in need of wheat and flour to sustain their populations.

Hopkinsville Milling Co. formed through the merger of two existing milling operations in 1908. Crescent Mills, founded in 1874, had made a big name for itself when it opened as the first steam-powered mill operation in the county. Located at Seventh and Railroad downtown, the mill could operate without being located near a water source. Crescent Mills produced a number of brands of flour including the Sunflour brand that we all know and love.

Climax Mill established a large operation in 1906 in the strategic location where the Illinois Central and L&N railroads intersected at 21st and Walnut streets. Two years later, Crescent and Climax mills merged to create Hopkinsville Milling Company. The newly-named industrial power established itself in the larger Climax mill site — where it still operates today.

In 1949, Hopkinsville Milling Co. sifted its way into a national story when it became a supplier of flour as part of the Marshall Plan. I found an article in The Knoxville Journal dated Feb. 28, 1949, that detailed how both Kentucky and Tennessee had a strong stake in the economic aid plan through the export of cotton, tobacco, and flour to European countries. In a list of manufacturers providing goods to the efforts is our own mill that sent $18,000 worth of flour to the Netherlands.

And I bet that flour was sent in a big, 50-kilo burlap sack like this one.

In a quick chat with Robert Harper last week, I learned that participating in this program was tough for a smaller, regional mill. Orders for flour to be exported were huge — much bigger than our mill could produce. It is likely that multiple mills across the South worked together to make the quantity needed to fulfill one of these large orders.

But by working together, these small town American mills participated in international foreign affairs by providing aid and assistance to countries in need.

Alissa Keller is the executive director of the Museums of Historic Hopkinsville-Christian County. She’s a graduate of Centre College with degrees in history and English and of Clemson University/College of Charleston with a master’s degree in historic preservation. She serves on the Kentucky Historical Society and the Kentucky Museum and Heritage Alliance boards.