The book is bound in bright red and is one of 65 volumes. The handwritten pages inside contain information of false alarms and of total destruction. Our artifact this month is simply a piece of paper, but it tells the story of one of the most iconic buildings in Hopkinsville. Or, part of its story, at least.

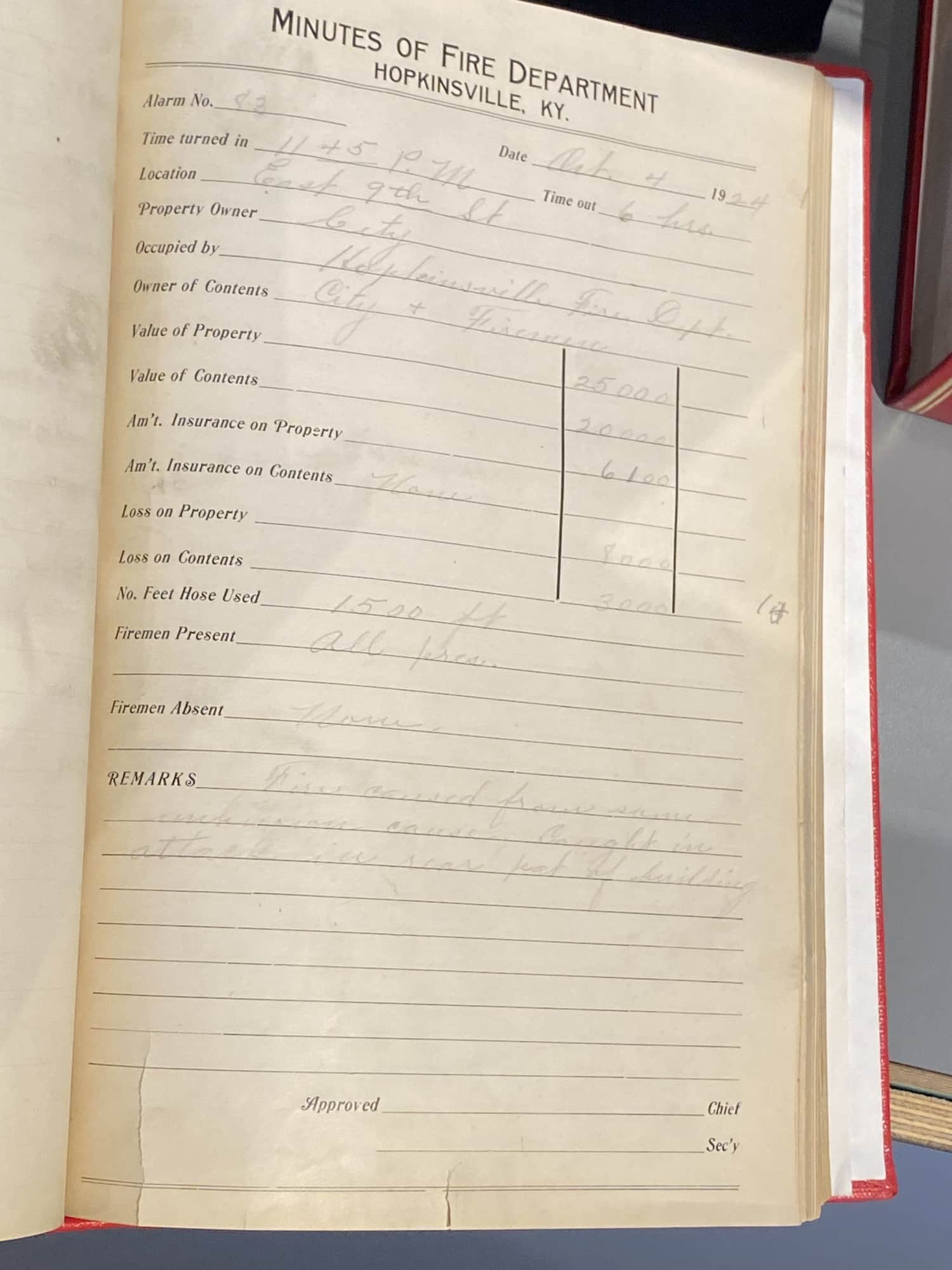

This month, we are taking a look at the fire run records of the Hopkinsville Fire Department. Dating back to 1889, the museum’s collection of these precious volumes spans the entire 20th century. Every run the fire department made — from the smallest to the biggest of blazes — is documented in these books. Each page contains valuable information: the date and time of the fire call; its location, property owner and occupant; the value of the property and its contents, as well as the amount of insurance carried on both; the length of time the department spent on the call; the number of feet of hose used; the firefighters present and absent; and any remarks about the fire.

Today (and for the past 20 years), these records are kept digitally. Luckily for us, the older paper files were scooped up and carefully bound so that we can use them as a resource.

The specific fire run record in question for us today is from Oct. 3, 1924. The pencil writing has faded to the point of being almost illegible, but a careful eye can still make out the details. The call came in at 11:45 p.m., and the fire was fought for six hours. The property owner is simply listed as “City,” and the building was occupied by the Hopkinsville Fire Department.

Yep! Hopkinsville’s Central Fire Station burned in a fiery blaze.

A new fire station for Hopkinsville

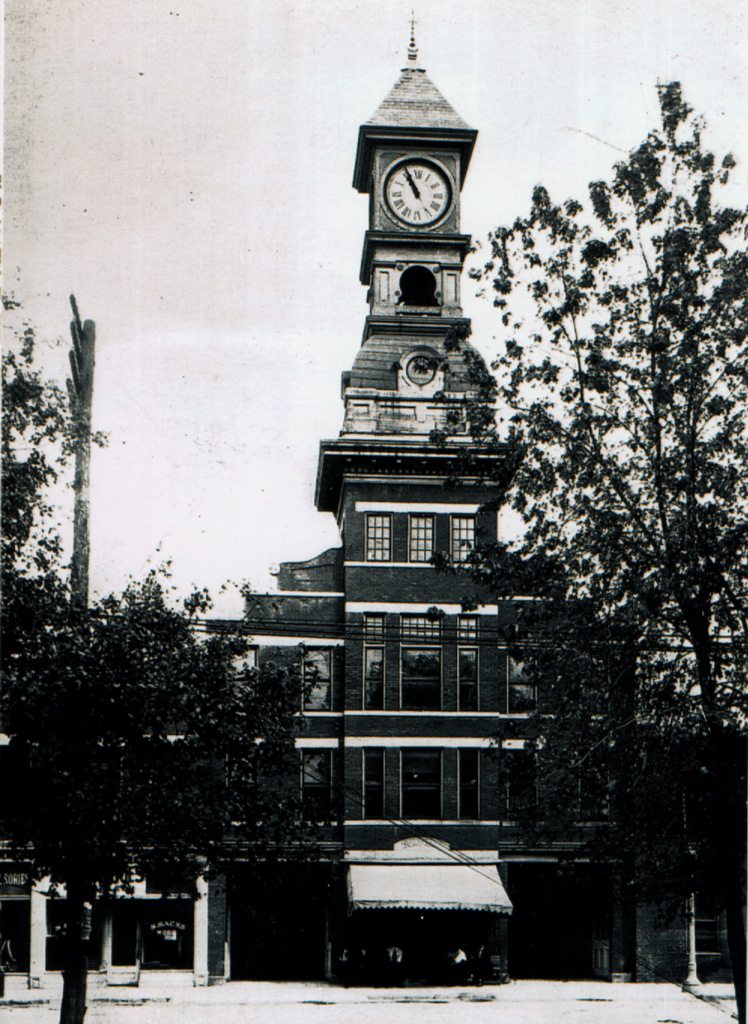

Constructed in 1904-1905, this stately structure stood on East Ninth Street — precisely where the fire station would remain until 1964 and where today’s Woody Winfree Fire-Transportation Museum survives. The lot was purchased by Hopkinsville’s City Council in March 1904, and the contract to erect a new city fire department building was awarded to Forbes Manufacturing Company that December. Forbes operated a virtual monopoly on local business at the time — with a construction company, a wagon factory, a blacksmith shop, and so much more. All told, the two Forbes brothers owned more than 20 businesses at the turn of the century.

The Hopkinsville Kentuckian identified Mr. W.A. Long as the constructor and general superintendent for Forbes. Assisted by George E. Randle, chief of the fire department, the two served as the architects for the building and all of its interior design made specific to the department’s needs. The first floor was reserved for fire equipment and to house the department’s equine firefighters Jouett and Lucian.

The second floor contained the firemen’s sleeping quarters — complete with beds, rugs and wardrobes for each of the five men who would stay at the station. This floor also boasted a banquet hall, a bathroom with a porcelain-lined tub, and a complete apartment for one man and his family. The wife of this firefighter prepared meals for the crew.

The second floor also featured a trap door through which protruded the brass pole that gave the firefighters access from their bunks to the first floor in a hurry. The trap door was just one of six automated aspects of the building. On May 23, 1905, just three days after the firefighters moved in, the Hopkinsville Kentuckian got an exclusive tour and reported the following:

“Downstairs there are a great many things that you don’t see until they are shown, and you don’t understand until they are explained. You notice a board in front of the six ‘keys’ one marked ‘light,’ two marked ‘trap,’ three ‘horses,’ four ‘hose wagon,’ five ‘doors,’ and six ‘alarm.’ As soon as the fire alarm is turned in the entire building is lighted as bright as day, the stall doors fly open, the horses rush under their suspended harness, the fireman’s trap is opened, the large front doors spread open and fasten, and in about one minute or less, the department is on the way to the fire. This is as complete an arrangement as can be conceived.”

What a set up!

A couple of weeks after the fire department moved into the building, they offered an open house for the community. Between 3,000 and 4,000 people crammed themselves inside (which must have been, ironically, quite the fire hazard). After enjoying refreshments and taking a full tour, folks were treated to a demonstration of the department leaving on a fire run. The mock alarm came in from Gray’s stable. It took six seconds to take the call, to inform the Home Telephone Company that the alarm was just a test, and to sound the alarm. And 16 short seconds after that, the department was ready to go. From the time the call came until the firemen, wagons, and horses were out the door was only 22 seconds!

Soaring 85 feet above the building was a clock tower, constructed as a focal point to house the city’s town clock. The clock and its bell were installed in the building on March 13, 1905, after being removed from the cupola of the courthouse during a renovation in 1903. Initially purchased in 1887, the clock and bell had been out of running order for a couple of years and found a new, appropriate home high above Ninth Street.

For almost 20 years, the department operated out of this fine facility. That is, until long after dark on the night of Oct. 3, 1924.

The night of the fire

That evening, seven firemen — John Lawson, Charles Dulin, Chief Ernest Haydon, Joe East, Guy Smith, Otto Fish and Joe Fish — were sleeping in the second floor bunk room. One more firefighter, Herman Johnson, and his family snoozed in the adjoining apartment when they were awakened by the sound of falling plaster and the cries of people outside. By the time they became aware of the fire, the blaze raged between the ceiling and the roof, making it incredibly difficult to access.

Working quickly, the firemen got all people — some still in their night clothes — and the fire trucks out of the building before the tower fell directly into the sleeping quarters below. Dramatically, the town clock was said to be striking midnight as it collapsed into the street.

According to the fire run record, the fire began by “some unknown cause” and caught in the attic in the rear part of the building. Faulty wiring has since been blamed for the conflagration that left the station with a gutted second floor and without a roof or tower. The department operated out of a nearby stable for the next few months as they anxiously waited for the building’s reconstruction.

A rebuilt headquarters — with one big difference

That reconstruction happened very quickly. By Jan. 12, 1925 — barely three months after the devastation — the fire department moved back into their headquarters on East Ninth Street. The side and rear walls from the original structure were incorporated into the new building, and a new front wall featured rough finish red brick. Other changes were made to the structure to make it function more efficiently for the modern use of fire trucks and other equipment.

But the rebuilt structure differed drastically in one way: it didn’t have a tower. The tower and town clock were not provided for in the budget for the reconstruction. Within days of the fire that brought the tower crashing down, the newspaper reported that it was probable the town clock would not be replaced. It posed the question “do you think we need one?” and received positive responses all around. Suggestions were made that private subscriptions be solicited to raise the funds to build a tower and install a clock. Responses to this idea were more divided.

And yet, when there’s a will, there’s a way. Thanks to the efforts of the local Woman’s Club, the money was raised to purchase a new town clock. The tower was added in 1926, and the new clock was installed in January 1927 by the E. Howard Clock Company from New York City. Its installation cost more than $2,000 and was given as a New Year’s gift to the city by the local philanthropic women’s group. The original fire bell from 1887 was saved and continues to strike the hour today — 136 years later.

The Hopkinsville Fire Department made their last run out of the Central Fire Station on East Ninth Street in May 1964. This last run did not involve a fire, but rather moved the station’s headquarters from its historic location to a new space in the urban renewal area on East First Street.

The building was utilized as a warehouse for Standard Mill Supply and as Firehouse Antiques before being left vacant. In 1997, it was purchased by the Local Development Corporation from Centre College (after being left to that institution in the estate of Golladay LaMotte) with the intention to turn it into a museum. In 2008, the Woody Winfree Fire-Transportation Museum — named for longtime enthusiast and collector of local fire memorabilia — opened in this storied structure.

Continuing to inspire

On Friday, March 31, the building suffered damage due to straight line winds. While we dug through the fallen bricks, we found many that were singed and blackened from the smoke of that 1924 fire. We saved those bricks in hopes that we can reuse them in one way or another. The museum staff and board are working on plans to fix and renovate the building once again. If it can survive a major fire, then it can surely continue to thrive and serve this community in new ways.

We started our story with a simple, one-page report, and look how far it brought us! That’s my favorite part about history and about working at our local history museum. Even the most mundane of objects can tell bigger stories and give us insight into our past and how that inspires and affects our present and future.

This was just one page. Imagine what other stories can be discovered within the 65 volumes of the Hopkinsville Fire Department’s Fire Run Records?