When sickness sweeps through a community, institutions suffer.

Because of COVID-19, schools and universities are empty. Businesses and restaurants are shuttered. Hospitals face shortages. Churches have closed.

When looking at our history, the story of one Kentucky church reveals that institutions can thrive after enduring tragedy and illnesses. It also reminds us that historic buildings can teach important lessons.

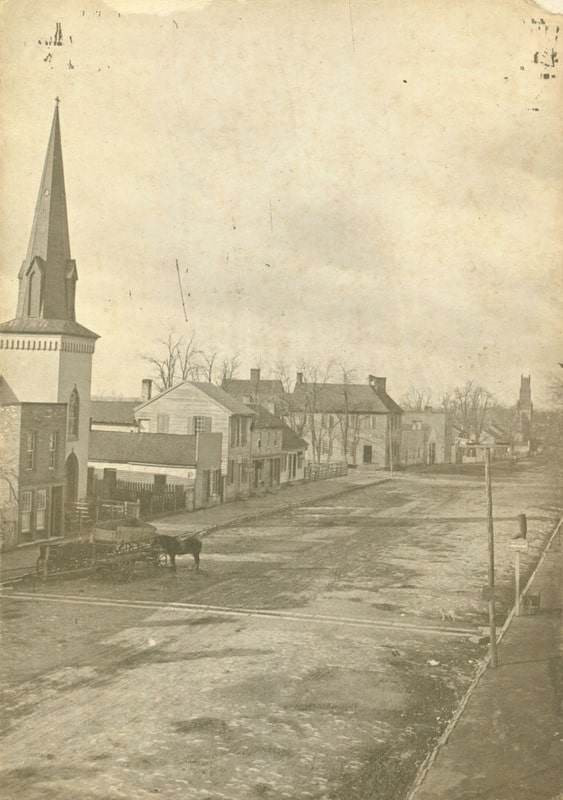

Built in 1830, Trinity Episcopal Church stands on Main Street in downtown Danville. Located across from the county courthouse, its sharp steeple and bright red door make it a visible community landmark.

Calamity soon struck the congregation. In 1833, cholera swept across the commonwealth, killing hundreds. Few communities were immune. Lexington, for example, lost more than 500 people. Smaller towns, including Maysville, Somerset, Paris and more, also suffered.

Danville was no exception, and the epidemic took the minister of Trinity Episcopal.

The Rev. Gideon McMillan was a native of Ireland who taught at Kenyon College in Ohio before moving to Danville. During the cholera epidemic, McMillan fell ill after helping sick residents. He died from the disease on July 30, 1833.

Buried on site, McMillan’s grave is now located under the church’s altar. His original tombstone stands preserved outside of the building.

The 1833 cholera epidemic was Trinity Episcopal’s first brush with community illness. Nearly 30 years later, however, the church was again hit hard when the Battle of Perryville raged just 10 miles away.

As I explain in my book “Perryville Under Fire: The Aftermath of Kentucky’s Largest Civil War Battle,” the contending armies left thousands of sick soldiers in Danville. The courthouse, churches, businesses and private homes became full of men suffering from dysentery, typhoid and other illnesses. Nearly 200 men convalesced at Trinity Episcopal.

One Danville resident said that church members “were dreadfully distressed to think their church was being used as a hospital.” Another witnessed death in the sanctuary. Mary Harris, who delivered food to sick soldiers, said, “The first death I saw was a Federal soldier in the Episcopal Church.”

Ill soldiers occupied the church for nearly six months. Damages were severe. Stained glass windows, pews, prayer books and carpets were destroyed. Mary Harris said that “the walls were written over and blackened considerably.” Another resident added that “it had the appearance as if there had been vandals there.”

Although the congregation eventually repaired the damages, in 1918 they again contended with community illnesses. That year, the world endured the dreaded Spanish flu pandemic, which killed millions of people around the globe. Dozens in Danville perished from the virus.

State and local authorities acted quickly to slow the spread of the disease. On Oct. 7, when 25 cases of the flu appeared in Danville, the local board of health quarantined sick residents. That same day, the state board of health closed theaters, schools and churches. They also banned public gatherings and prohibited people “from visiting each other’s homes.”

This slowed, but did not stop, the spread of the virus. The entire family of Mr. and Mrs. E. L. Noel, for example, who lived near Trinity Episcopal on West Main Street with their five children, all battled the flu at the same time. Members of the church’s congregation undoubtedly suffered from influenza during that pandemic.

Trinity Episcopal experienced cholera epidemics, the aftermath of Kentucky’s largest Civil War battle and the 1918 flu pandemic. Despite this, resilient congregations from different eras overcame challenges brought by devastating illnesses.

Today, we can learn from this history. In the face of COVID-19, just as the congregation of Trinity Episcopal dug in their heels and continued to thrive, our communities can work together to make us stronger than ever before.

Not only can this building tell us a story, it can also inspire us.

Stuart W. Sanders is the Kentucky Historical Society's Director of Research and Collections. His latest book, “Murder on the Ohio Belle,” examines Southern honor culture, vigilante justice and the Civil War through the lens of an 1856 murder on a steamboat. Find him on Twitter @StuartWSanders.