More than a few of our foolhardy forebears rang in the New Year with earth-trembling blasts that threatened — and sometimes claimed — lives and limbs.

Called anvil-firing, the ear-splitting holiday custom was forsaken long ago, possibly because it proved so hazardous. (The custom is preserved — safely — at special events held annually around the country.)

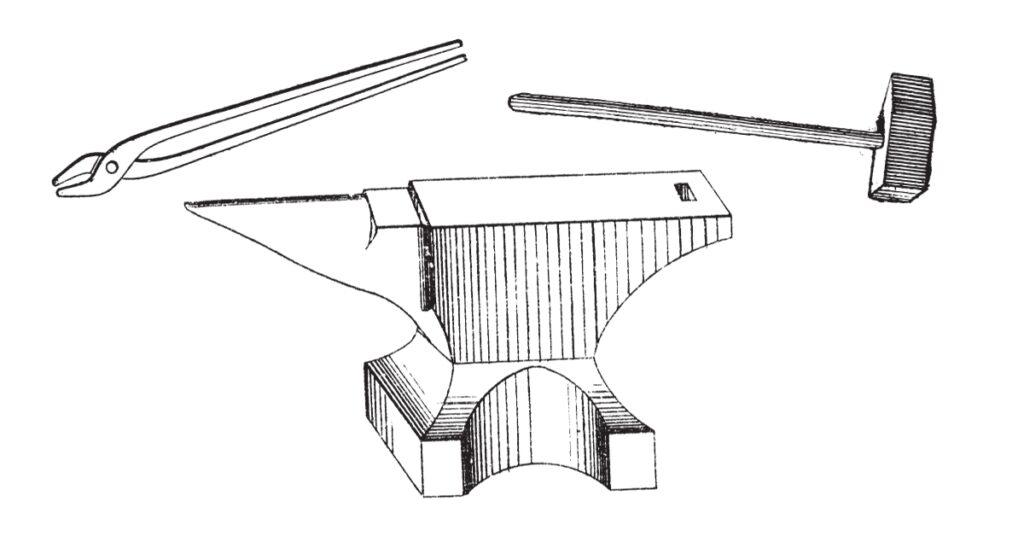

The revelry started when the firing crew lugged a pair of matched anvils to a field or some other open space. They’d place one anvil atop the other one — the bottom anvil upside down, the top one right side up.

Anvils have little cavities or holes on their undersides. So the crew would pack black powder into the mated cavities, stick in a fuse, light it and stand back, hopefully at a safe distance.

The smoky blast would launch the top anvil, called the “flier,” skyward. Everybody watched the anvil’s flight to lessen the chance of somebody getting hit on its return trip to earth.

But sometimes anvils burst, sending chunks of flying iron in all directions and killing and maiming firing crews and spectators.

No matter, anvil-firing was also popular at Yuletide — so much for “Silent Night” — and on the Fourth of July. Anvils were fired to celebrate election victories, too. (The booming that echoed off Frankfort hills on Dec. 12 was from a cannon salute in honor of Gov. Andy Beshear’s second inauguration.)

Old Kentucky newspapers reported horror stories of anvil-firing disasters. Readers weren’t spared the gory details.

- RELATED: Revolutionary-era trunk carried stories of nation’s past to Hopkinsvilleanvil-firing, the ear-splitting holiday custom

For example, on Christmas Day 1888, a Fleming County man decided to celebrate the birth of the Prince of Peace by disturbing the peace with an anvil firing.

The blast blew up one or both anvils. He “was terribly mangled,” reported the Maysville Evening Bulletin, and “can not survive.”

On Christmas Eve, 1895, a Garrard countian “was celebrating Christmas by firing a blacksmith anvil,” according to the Louisville Courier-Journal. “One charge failed to explode promptly, and it went off while he was leaning over it.”

The detonation tore off “his right hand and arm and part of his face and head.” Doctors didn’t expect the “well-known and popular young man” to live.

On Jan. 1, 1896, the Richmond Climax published a slightly different version of what befell the youth, perhaps to deter New Year’s Day anvil-firers. “He was pushing the powder into a hole in the anvil with a large rod of steel, and struck too hard, causing a spark to ignite the powder and explode the anvil.” The paper also said the man would likely die.

An even worse anvil-firing mishap ended as many as four lives — three of them bystanders — in Burkesville, the Cumberland County seat, on the evening of Nov. 6, 1886. Local Republicans were whooping it up over Dr. W. Godfrey Hunter’s election to Congress.

“Contrary to the advice and wishes of many of the citizens, they placed a couple of anvils in the Court-house yard, and commenced firing them,” the Courier Journal informed its readers on Nov. 9.

Some citizens begged the GOP faithful “to carry their anvils somewhere else.” They declined and after “about fifteen or twenty minutes … one of the anvils burst.”

A fragment hit a young man who was watching the show from a drug store doorway. He died instantly. We will spare you the gory description as reported in detail by the C-J.

Other flying debris tore the legs off the county jailer, who was part of the firing crew, and another man. Doctors believed both would perish, according to the Louisville paper.

Too, the county assessor’s son “had little chance to pull through after he was “struck in the side by a piece of the iron and dangerously wounded.”

The rally “was, of course, immediately terminated while the whole town was thrown into gloom,” the paper said.

Though popular in Kentucky of yore, anvil firing is a European import.

Clement is the patron saint of blacksmiths and metalworkers, so they would honor him with drinking, feasting and anvil-firing on St. Clement’s Day,Nov. 23, according to Everything Catholic online, which says the custom persists “in some places to honor St. Clement, but it is also enjoyed as a fun and exciting spectacle.”

Blacksmiths and their apprentices took the day off and “dressed up in a wig, mask, and cloak to represent ‘Old Clem,’” the website also says. “He led a procession of smiths through the streets, stopping at taverns along the way. Boisterous singing was followed by demands for free beer or money for the ‘Clem feast.’”

The website advises that customary toasts ranged from “True hearts and sound bottoms, check shirts and leather aprons” to “Here’s to old Vulcan, as bold as a lion, A large shop and no iron, A big hearth and no coal, And a large pair of bellowses full of holes.”

Boozing and blasting anvils. What could go wrong?

This article is republished under a Creative Commons license from Kentucky Lantern, which is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Kentucky Lantern maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Jamie Lucke for questions: info@kentuckylantern.com. Follow Kentucky Lantern on Facebook and Twitter.

Berry Craig, a Carlisle countian, is a professor emeritus of history at West Kentucky Community and Technical College in Paducah and the author of seven books, all on Kentucky history. His latest is "Kentuckians and Pearl Harbor: Stories from the Day of Infamy" which the University Press of Kentucky published.