For some of us, our resolve is cracking.

Weeks spent at home avoiding the coronavirus has been tiring. We’re depressed. Our resilience is fading.

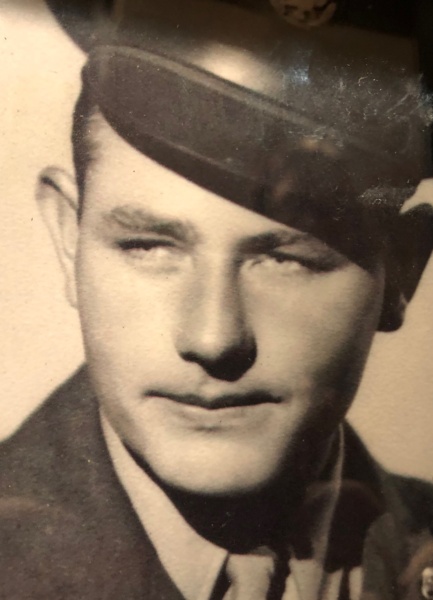

Specifically, I think about my wife’s paternal grandfather and how he spent the first 20 years of his life.

D.C. Neighbors grew up in Butler County, Kentucky, during the height of the Great Depression. In rolling fields close to the Green River, his family scratched out a hard living with neither electricity nor running water. Farming meant tending a small patch of ground and plowing with mules.

I once asked him what he did during his free time. His blue eyes — the clearest blue I’ve ever seen — gleamed. He then cracked his wry grin.

To bolster my patience, I remember the Americans who endured the Great Depression and the shortages and horrors of the Second World War.

- SUPPORT US: Like what we do? Consider making a donation to the Hoptown Chronicle, a nonprofit news organization

“Now Stu,” he exclaimed, “there wasn’t no free time. If I wasn’t working on the farm, I was chopping wood.”

Around age 18, he moved to Indianapolis to work. He spent that summer building roads, which involved hauling metal ties and covering them with concrete under a blazing Hoosier sun.

Shortly thereafter, he joined the U.S. Army. At Camp Fannin, Texas, he told his fellow recruits that their basic training was like a vacation because they had time to rest. The other soldiers, he told me, thought he was crazy. He was also the only man in his company to gain weight because he was working less and was finally eating three square meals a day.

When D.C. qualified with the M-1 Rifle, he shot so well that the base commander said, “I’ll bet any man a steak dinner that he’s a Kentucky squirrel hunter.” Indeed, he was.

Within weeks, D.C. found himself in the jungles of the Philippines, fighting the Japanese. He first encountered enemy fire after landing on the island of Leyte. When he saw tracer rounds zipping from an enemy machine gun, he decided that he wouldn’t survive the war.

That’s an incredible burden for a 19-year-old to carry.

When his unit engaged the enemy on the island of Negros, a Japanese light machine gun pinned down one of his friends. Now a hardened combat veteran, D.C. stood up and emptied a magazine from his Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR) into the enemy emplacement, silencing the gun.

Immediately, a Japanese soldier popped out of a hole and shot D.C. in the chest. D.C.’s friend, who had been pinned down by the machine gun, then killed the Japanese soldier with a hand grenade.

Although he had been shot in the chest, D.C. finished the firefight. When it was over, he exchanged his BAR for an M-1 Rifle and walked by himself 4 miles though the enemy-infested jungle.

“Weren’t you terrified?” I once asked him.

“Nah,” he replied. “I had my rifle.”

Following surgery to remove the bullet — which had nearly struck his heart — D.C. returned to his unit, which was preparing to invade Japan. He would have been part of the second wave to hit the enemy island. Instead, after the U.S. dropped two atomic bombs, Japan surrendered.

He guarded an airbase in Japan and worked at a U.S. Army prison in California before hitchhiking back to Indiana. There, he spent more than 40 years working for General Motors in Indianapolis, where he and his wife, Virginia, raised two children.

As a child of the Great Depression, he took every opportunity to earn a dollar. He once worked at GM for 18 months straight, seven days a week and holidays, without a day off. Most of those days were at least 10-hour shifts.

Although D.C. survived World War II, he was almost killed while working. Crushed between two massive dies hauled into the plant on railroad cars, it took him months to recover.

When D.C. died in Plainfield, Indiana, in 2018, he was 94 years old. He had enjoyed a great retirement, full of travel, loving grandchildren and, I think, gratitude.

This man, who had known great deprivation and extensive suffering, was one of the most generous people I have ever known. He was also one of the most resilient. Truly one of the greats from “The Greatest Generation.”

Now, when I feel my will breaking and my patience ending, I think of D.C. Neighbors and what he experienced.

And I smile and turn on my green porch light. And I know that we, too, can endure.

(Stuart W. Sanders’ latest book is “Murder on the Ohio Belle.” He’s on Twitter @StuartWSanders. Email him at perryvilleunderfire@gmail.com)

Stuart W. Sanders is the Kentucky Historical Society's Director of Research and Collections. His latest book, “Murder on the Ohio Belle,” examines Southern honor culture, vigilante justice and the Civil War through the lens of an 1856 murder on a steamboat. Find him on Twitter @StuartWSanders.