These 10 letters are part of an 18-letter set that dates to the 1880s. Likely made from the same material used in pressed tin ceilings, the largest letters in the set are 21 ½ inches tall and 8 ½ inches wide. The ones pictured here are 10 inches tall and 6 ¾ inches wide. The silver-painted letters are lightweight and show the rust and wear-and-tear of outdoor exposure. Designed to hang on the front of a structure, they are made with a drop shadow, making them appear three-dimensional.

As I’m sure you have guessed, the letters not pictured spell the name HOLLANDS.

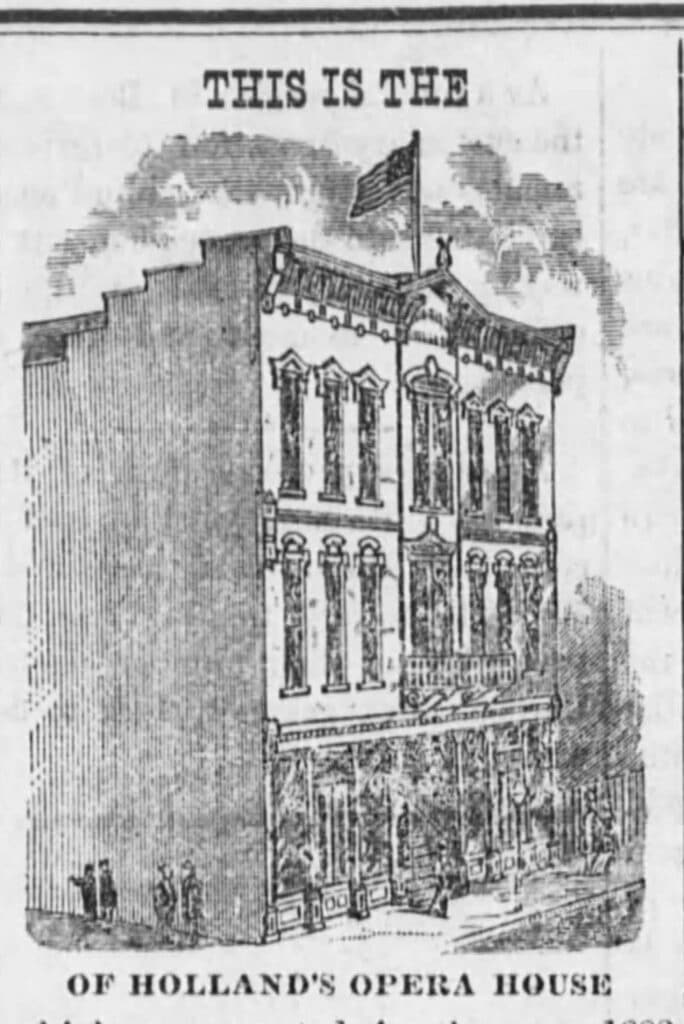

All together, they spell Holland’s Opera House, and they once hung near the top of a three-story structure built in 1882. The top floor was lost in 1967 and the remaining structure was removed from our downtown streetscape over the past few weeks. Today the letters hang in an exhibit at the Pennyroyal Area Museum. Their provenance is a mystery to us, but we are thankful to have them. Especially now. What story do they tell?

These letters tell the story of a cultural centerpiece of our community in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Built and owned by Richard H. “Dick” Holland, the building promoted arts and entertainment of all kinds. The auditorium on the second and third floors was state-of-the-art when it opened. A couple of days before its debut, the South Kentuckian newspaper ran a piece describing it as “the finest in the city.” The full description is fascinating. I cannot bear to leave out any detail as it was given in 1882. Here’s what they had to say:

The building is three stories high in front, and the front is the handsomest in the city. It is surmounted by a lyre and a flag pole. Over the entrance is a large iron balcony, eight feet in width. The main entrance is broad and the gradually ascending stairway leads to a lobby which is elegantly finished, and brilliantly illuminated with a magnificent cut glass chandelier, which hangs over the front of the box office, at the head of the steps. This is in the shape of a Moorish pavilion, and on either side are the entrances to the main floor and manager’s office.

There are two doors opening into the auditorium, which is 65 feet deep, by 50 feet wide, and 32 feet high. The parquet and dress circle have a seating capacity of over four hundred, and they are seated with folding chairs [furnished by A. H. Andrews of Chicago] with foot rests and hat racks underneath. The gallery seats about three hundred, making a total seating capacity of over 700.

The walls and ceiling are elaborately papered, the ceiling being especially handsome. In the center, over the parquet, is a pendant circular light, of thirty-six gas jets, with a brilliant reflector above. The orchestra for musicians, is slightly below the rest of the floor, which keeps them from obstructing the view. The proscenium [the part of a theater stage in front of the curtain] must be seen to be properly appreciated. It is finished magnificently and elaborately decorated with artistic skill. It has on either side doorways, instead of boxes, through which encores can be re-responded to without having to pull back the drop curtain, which is always embarrassing and awkward. The side lights are of cut-glass, with crystal prism pendant. The 200 jets of gas will be lighted by electricity, the apparatus for which was fitted by Mr. J. W. Braid, the electrician in Nashville.

The stage opening is 28 feet wide by 22 feet high, the stage proper being 45 feet deep by 50 feet wide, and it is fitted with the latest improvements in the way of lights, curtain hoists, and properties. It is stocked with 32 sets of scenery, consisting of flats, borders, wings, “set-stuff,” etc., and it is amply supplied with stage furniture, carpets, water-works and four well-appointed and handsomely furnished dressing rooms.

WOWZAS! What a spectacle on Hopkinsville’s Main Street! Additional details included the particulars of the fire prevention plan that allowed for the theater’s full capacity to be cleared in less than four minutes. The first floor contained space for two businesses — one on each side of the staircase leading to the auditorium — but the opera house was clearly the focus of the building.

All told, the theater took almost a year to construct and cost between $25,000 and $30,000 to build and outfit in such an extravagant fashion. That amounts to upwards of $750,000 today. R.H. Holland, the proprietor, was only 23 years old when the opera house opened its doors. Born in 1858 and orphaned in 1867, he must have inherited his father’s estate, which according to the 1860 Census amounted to $45,000. Young Holland moved to Hopkinsville to live with his uncle D.S. Beard on 14th Street. In the 1880 Census, he was living in Pembroke and was listed as a farmer. Within two years, he built the up-and coming cultural center of Hopkinsville.

Holland’s Opera House officially opened on Friday, Sept. 22, 1882, to an over-packed house of 700 with a comedy-drama play. Tickets cost $1.50 each (about $45 today) to see the talented young actress Minnie Maddern. The Chicago Morning News said of her: “Her fun bubbles up like a fountain, and her pathos melts into involuntary tears, like an April shower.” Maddern performed the lead in “Fogg’s Ferry,” a dramatic adaptation of the thrilling novel of the same name by Charles Edward Callahan. The 17-year-old actress began her professional career at the age of 3 when she was reportedly paid in lollipops. She expanded to playwright and director and starred in two feature film adaptations of her stage roles. And an audience in Hopkinsville got to see her perform on their own stage!

Just one month after its grand opening, Holland’s Opera House survived a major disaster. On Oct. 25, 1882, a huge fire swept through downtown, destroying numerous businesses and homes and leaving behind a seven-block trail of devastation. R.H. Holland narrowly escaped death when he was crushed by the falling wall of a nearby building. He was pulled to safety, and his new opera house managed to escape the blaze.

His response to the fire? About two weeks later a benefit concert was held at the opera house. Put together by the Ladies Christian Aid Society and under the supervision of Emily B. Perry, the concert and live auction featured local talent assisted by the Hopkinsville Orchestra. Donations of flour and other supplies were received, and together with the money raised, all was distributed to those left destitute by the fire.

Within two months of opening, Holland’s Opera House set the stage for the impact it would have on this community. The venue attracted traveling performances ranging from Shakespearean productions to Vaudeville shows, and it served as the place for the community to gather and celebrate — or rally around — each other.

I have started a list of performances held at the opera house during its heyday from 1882 until the mid-1920s. There were multiple performances in many weeks! Many shows were performed by traveling troupes from New York City, Chicago, and beyond. The list is long and still growing. Here are a few highlights:

- Oct. 14, 1882: Thatcher, Primrose, & West’s Minstrel Show. A problematically popular attraction at Holland’s throughout its life as a theater were minstrel shows. This one, performed just three weeks after the theater opened, was the first of many companies who would perform in blackface. Minstrel shows were an American form of racist theatrical entertainment that consisted of comedy skits, dancing, music, and variety acts.

- March 9, 1883: “The New Jane Eyre” starring Charlotte Thompson, a London-born actress.

- Oct. 17, 1883: “Richelieu; or The Conspiracy” starring Thomas W. Keene, a theater actor best known for his Shakespearean roles.

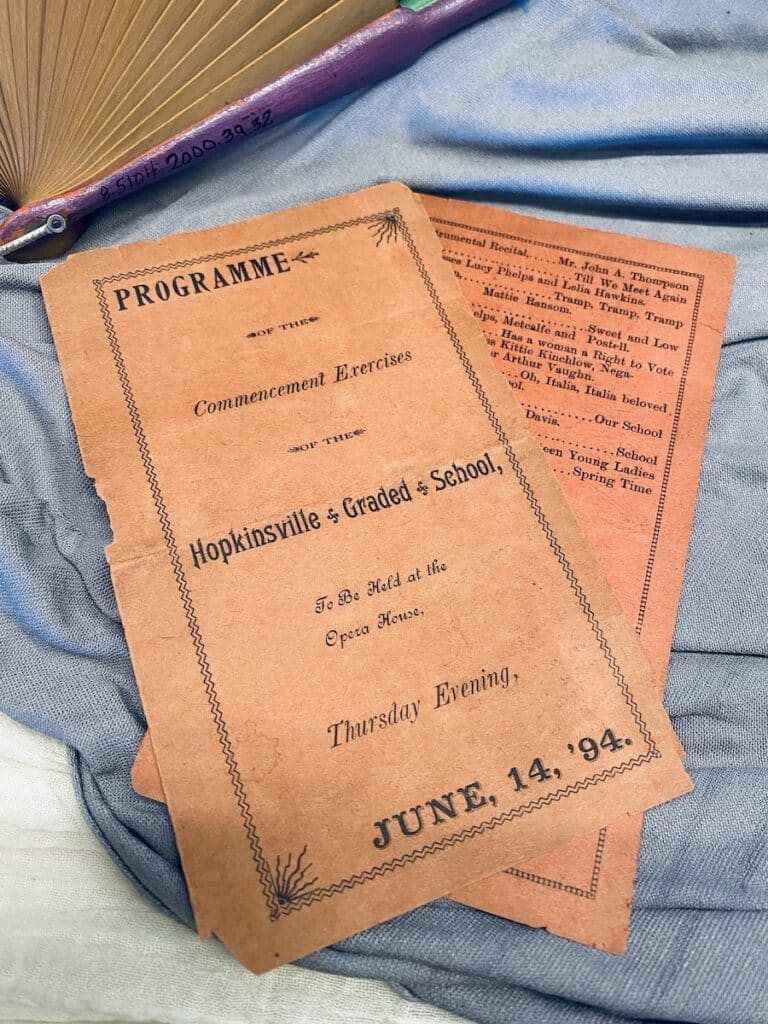

- June 14, 1894: Commencement Exercises for the Hopkinsville Graded School. This ceremony was for the African American schools and included choral performances, recitations, instrumental performances, and a debate on women’s suffrage. The Museum has a copy of the printed program on display.

- 1901: Hart the Laugh King, a hypnotist, performed at Holland’s Opera House where he hypnotized a young Edgar Cayce, thus launching the journey of Cayce to becoming the “Sleeping Prophet” and the most well-documented psychic of the 20th century.

- Sept. 29 and 30, 1905: “The World in Motion.” Holland’s Opera House was the site of the first moving picture show in Hopkinsville. This show in particular featured moving pictures of the fire department, the Third Kentucky Regiment at Camp Yeiser, and Col. Henry and Staff at dress parade.

- Feb. 2, 1911: “George Washington’s Bullion” by the Smart Set. The Smart Set was an all African American performance troupe starring Salem Tutt Whitney and Homer Tutt (later known as the Tutt Brothers). They performed multiple times in Hopkinsville. On at least one occasion, the entire theater was reserved for African American patrons. On another occasion, half of the lower floor was open to Black guests. These performances serve as an early, yet small, example of local integration in the arts.

- March 30, 1911: “Beverly,” a dramatization of the novel by Robert M. Baker and under the production of A.G. Delamater and William Norris. The show had debuted at the Original Studebaker Theater in Chicago and came to town with a “car load of scenery.”

- Sept. 18, 1911: “The Night Rider,” presented by the Rex Amusement Company. The play chronicled the outrages committed by “that lawless band of men” and presented the violence of the gang while showing the means to which they went to gain political power.

- March 21, 1912: “Merchant of Venice Up to Date” performed by students from McLean College. The performers included locals Emma Wilson, who would go on to publish the book “Under One Roof” and Emma Noe, who would become a famous opera soprano.

- Dec. 15, 1919: Baldheaded Club Meeting, with Uncle Dick Holland serving as its president. This meeting made the front page of the newspaper — and its recap is hilarious.

As for Holland (or Uncle Dick, as he was affectionately known), he never married and appears to have worked at the opera house (in an advisory capacity, I imagine) for most of his life. He died in 1930, and the opera house as a performance venue was relegated to memory. With three movie theaters — the Princess, Rex, and Alhambra — in town, the old opera house must have lost its flair.

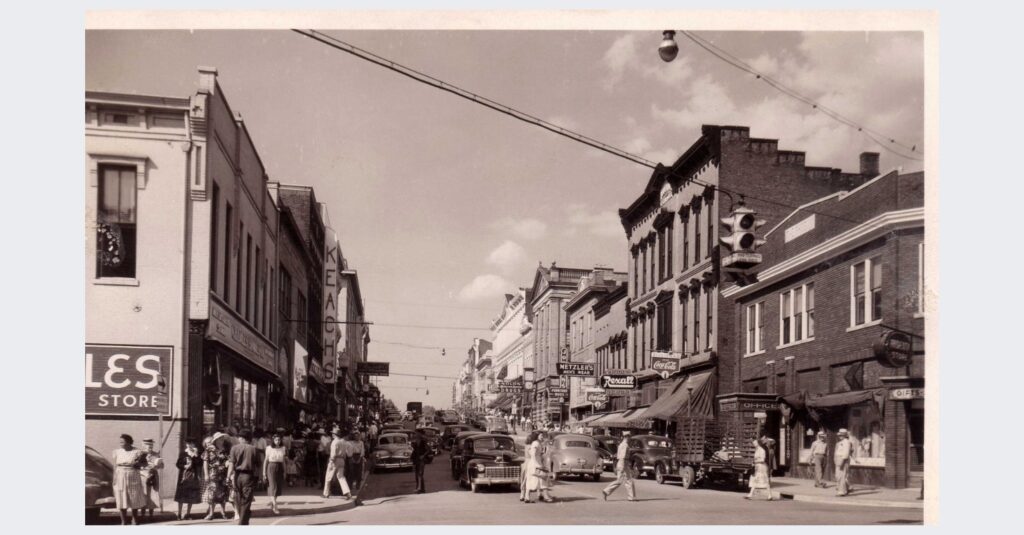

After his death, the second floor of the opera house auditorium was divided into offices. Real estate and insurance agents, a dentist, a women’s clothing store, and Means Jewelry Store all occupied space on the second floor. Dr. Rachel Croft and Dr. Norma Shepherd, Hopkinsville’s first two women medical doctors, opened offices on the second floor of the esteemed opera house in 1948 and remained until Shepherd moved out after 1958. By 1956, the Pennyrile Broadcasting Co. and radio station WKOA were operating from the second floor. WKOA was one of the final tenants when, on April 3, 1967, a failing beam from the roof above the third floor auditorium crashed through the ceiling and onto a broadcaster’s desk. Luckily, no one was injured.

Noble Hall Jr., owner of the building and local real estate agent, told the Kentucky New Era that the roof of the structure was sound and that repairs would begin immediately. I have not been able to figure out exactly what happened, but in fairly short order, the third floor of the building was removed. From 1967 until 2023, the building stood as a two-story structure with occupants only on the lowest level.

Businesses remained on the first floor until the 2010s. Most notably, Wood’s Drug Store operated out of the left bay at 808 S. Main St. with pool rooms and restaurants next door at 812 S. Main St. The building had been vacant for at least 10 years when the decision was made to tear it down due to severe structural issues.

But the legacy of arts, culture and philanthropy so present at Holland’s Opera House remain. This legacy continues at the Alhambra Theatre every time big name performers and local talent take the stage. It remains in our community’s dedication to supporting each other — like they did in that benefit concert in 1882 — through organizations like the United Way, Rotary Club, Salvation Army, Aaron McNeil House, and many more. And all of these stories remain in the 18 metal letters at the Pennyroyal Area Museum. Stories to be explored further and to be shared for generations.