A new report that evaluates the well-being of children in the United States every year shows that Kentucky is one of the worst places for youngsters to live.

In fact, the commonwealth ranked No. 40 overall for key indicators of well-being, including financial security, education and child deaths.

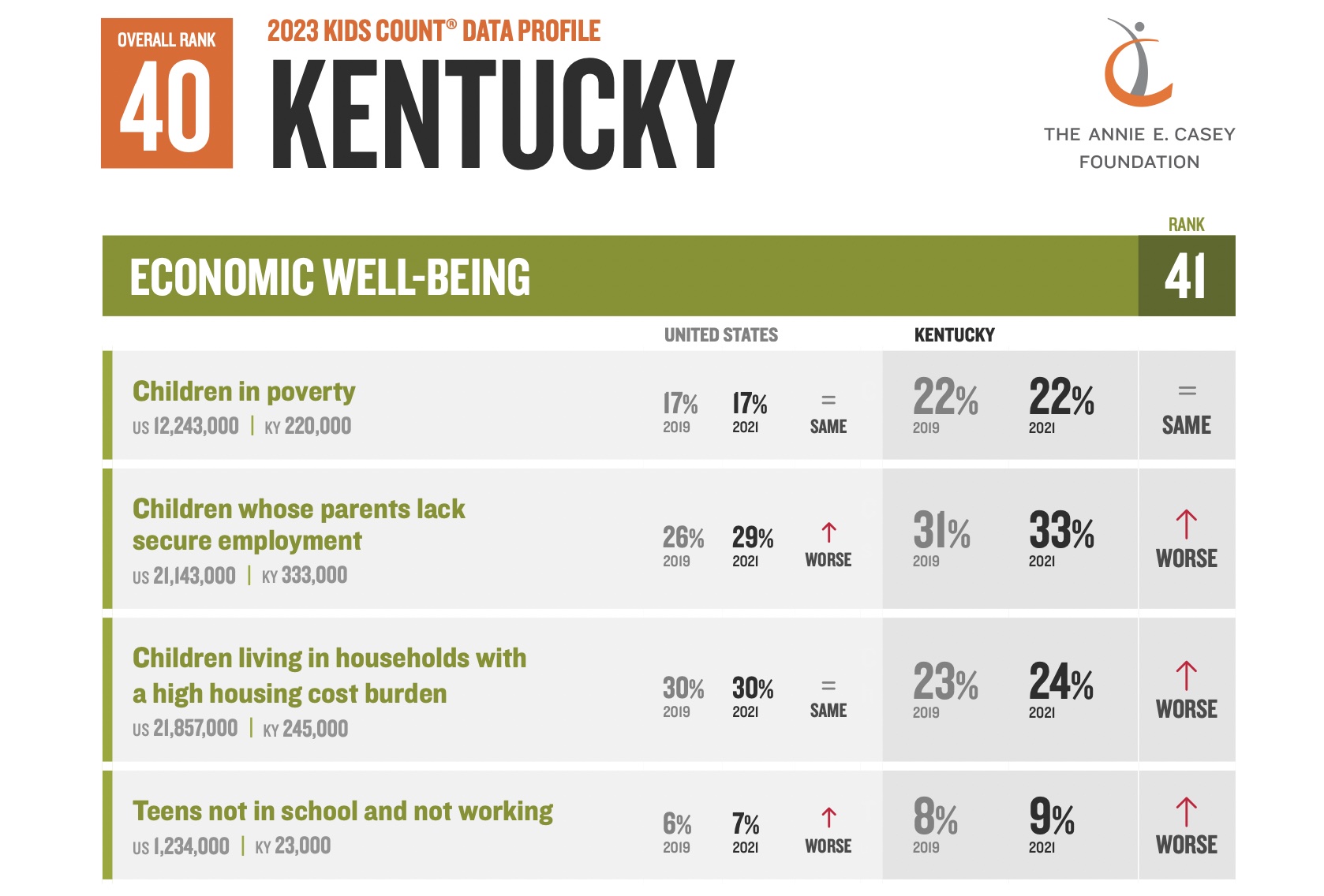

These numbers come from the annual Annie E. Casey Foundation’s KIDS COUNT report, released Wednesday. It shows Kentucky had more kids in 2021 whose parents didn’t have secure employment than in 2019.

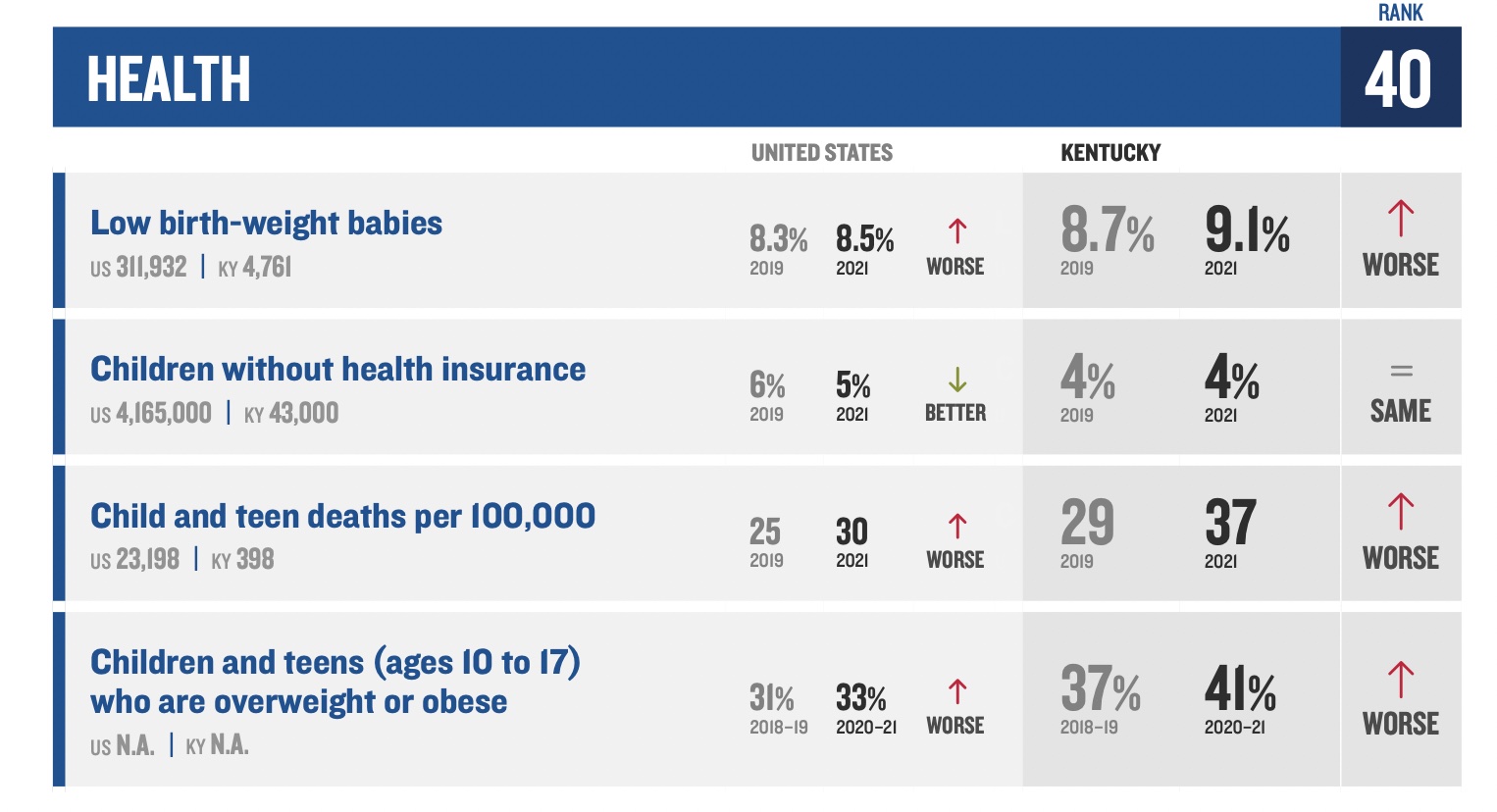

More teenagers were neither in school nor working – basically, unaccounted for, according to the report. More children died, though the causes aren’t clear. And: more babies were born underweight.

Terry Brooks, executive director of Kentucky Youth Advocates, said that much of the report is “disappointing” for the commonwealth.

“What we’ve learned in over three decades of KIDS COUNT data is economic well-being and, specifically, childhood poverty is the bellwether for what’s to come,” Brooks told the Lantern.

The “ripple effects of economic well-being is certainly a major factor” in overall health and prosperity. You can’t separate them.

Yet more than 200,000 kids lived in poverty in Kentucky at the time of data collection. But, that number was level with the numbers from 2019, meaning it’s at least possible for the state to head in the right direction in the next report.

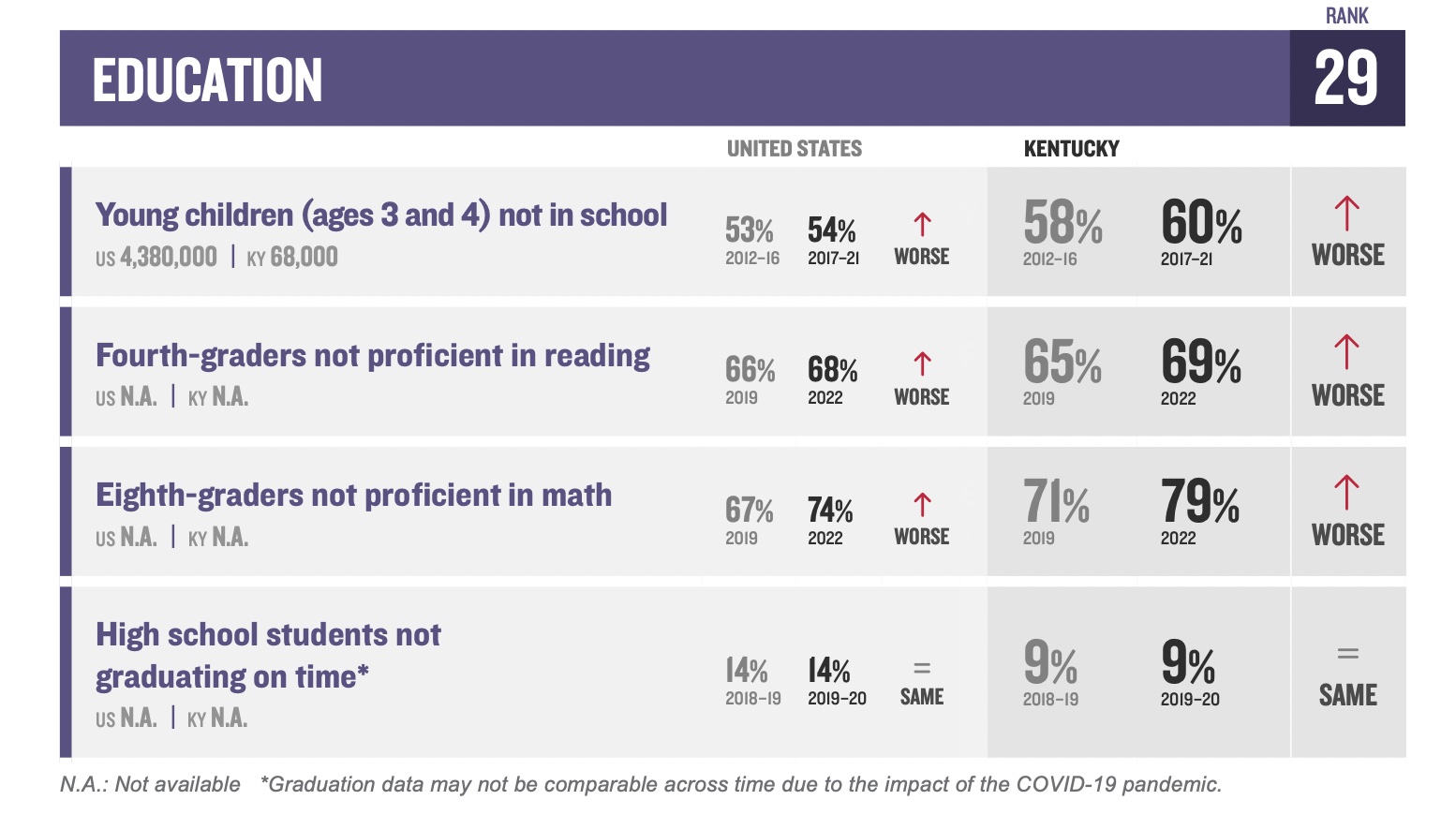

Educational data points were woeful, too.

More 3- and 4-year-olds were not in school from 2017 to 2021 when compared to 2012-2016. In 2022, more fourth graders showed reading incompetency and there was a large jump in the number of eighth graders who weren’t proficient in math.

The number of high school students who failed to graduate on time remained the same in 2021. However, the report notes that “data may not be comparable across time due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.”

“Maybe, just maybe, education policy in Frankfort should focus on reading, writing and arithmetic rather than every social agenda known to humankind,” Brooks said. “I think that that level of underperformance — maybe that’s a wake up call to the General Assembly that education committee meetings need to be about education and not all of the politically-charged issues that have dominated that agenda.”

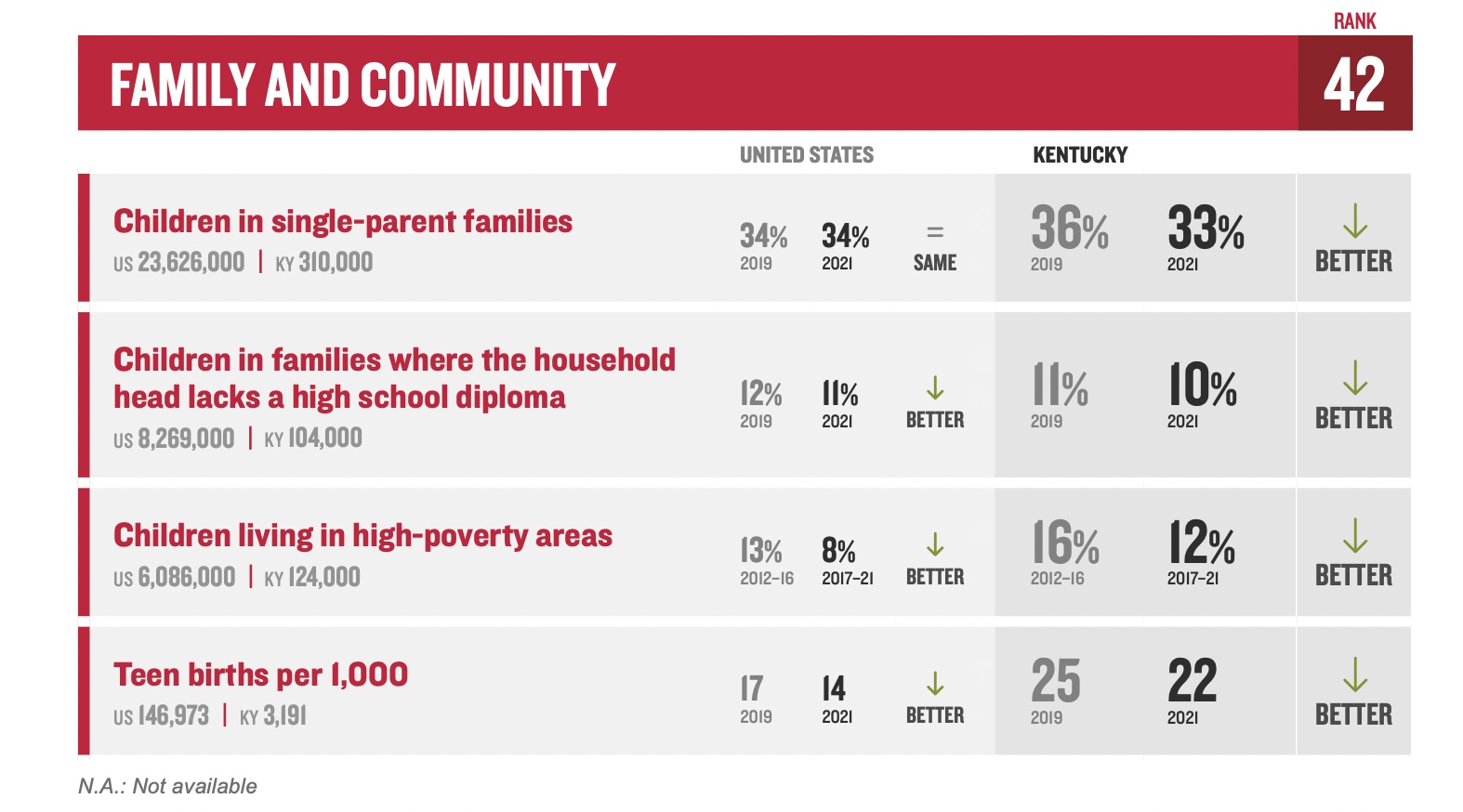

Kentucky did improve on a few points, the report showed. There were fewer children living with a head of house who didn’t have a high school diploma. There were fewer teen pregnancies.

And, fewer kids lived in high-poverty areas, though the number of children living in poverty remained the same: 22%, or 220,000 kids.

High poverty areas, AECF says, are areas in which the local poverty rate is 30% or higher. These neighborhoods “are more likely to have high rates of crime, violence, health issues and unemployment,” AECF reports.

Nationally, about 9 million children lived in such conditions, as of 2017.

Individual poverty is measured by comparing income and mouths to feed. A family is considered poor by the U.S. Department of Health and Human services if their income falls below these income thresholds:

- $29,967 for a family of five with three children.

- $25,465 for a family of four with two children.

- $20,231 for a family of three with two children.

Brooks said he’d like to see Gov. Andy Beshear and Attorney General Daniel Cameron, who are vying for the governorship — the former for a second term – to talk on the campaign trail about how their 2024 budget proposals would “embrace early childhood and childcare.”

“And then,” Brooks said. “Let’s see what the Senate and House do with those ideas.”

This article is republished under a Creative Commons license from Kentucky Lantern, which is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Kentucky Lantern maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Jamie Lucke for questions: info@kentuckylantern.com. Follow Kentucky Lantern on Facebook and Twitter.

Sarah Ladd is a Louisville-based journalist and Kentuckian. She has covered everything from crime to higher education. In 2020, she started reporting on the COVID-19 pandemic and has covered health ever since.