The head of the commission that manages Kentucky’s opioid-settlement money said Wednesday that the panel will “explore the possibility” of committing “no less than $42 million” to developing a treatment of opioid-use disorder with the psychedelic drug ibogaine, which is not legal in the United States.

Gov. Andy Beshear questioned the idea and said it was announced without consulting his two appointees on the Opioid Abatement Advisory Commission, which has yet to approve it. The commission operates under Attorney General Daniel Cameron, the Republican nominee against Beshear in the fall election.

Bryan Hubbard, executive director and chairman of the commission, told reporters at the announcement event: “It is our hope that we can achieve an approval within six years” from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for ibogaine.

“This is the first time an effort like this has ever been undertaken by an individual state in history,” Hubbard said. “So we are in uncharted territory by even discussing the possibility of executing this project.”

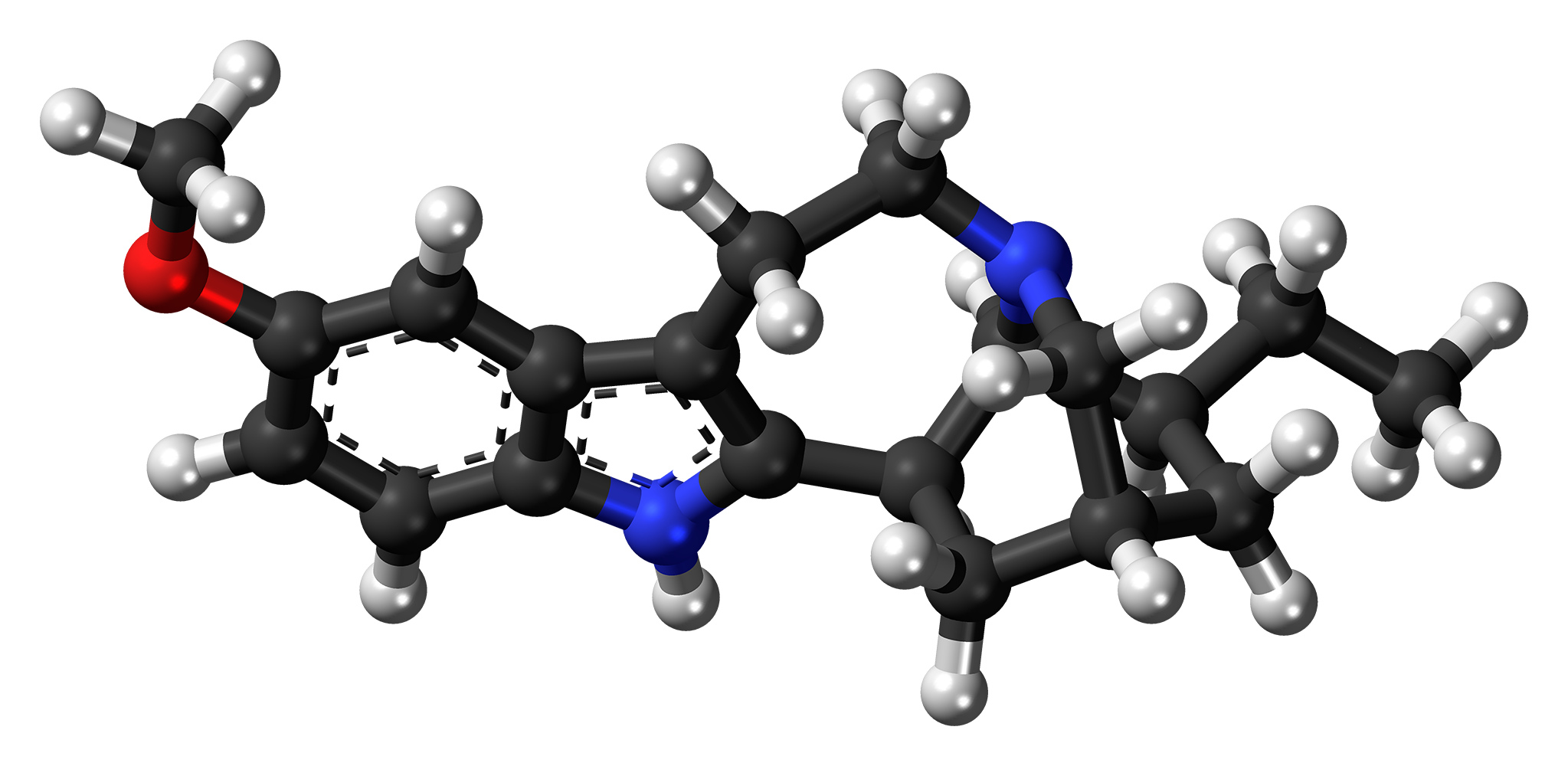

Ibogaine is a powerful psychedelic that comes from a plant mainly found in Africa. It is anecdotally reported to stop the withdrawal symptoms of opioid dependence.

“Anecdotal evidence that is a mountain high and decades wide, suggests that ibogaine, within 48 to 72 hours of administration in safe, clinically controlled conditions, resolves opioid withdrawal syndrome,” Hubbard said.

“It appears to do so by clearing and resetting the brain’s opioid receptors, while also restoring the brain’s organic dopamine and serotonin production to pre-opioid exposure levels. If this anecdotal evidence can be clinically validated, ibogaine would represent a transformative therapeutic for the treatment of opioid-use disorder.”

The commission’s news release about the idea did not mention any drugs, nor did Cameron in his opening remarks to a crowd of at least 60 who came to hear the announcement on the state Capitol lawn.

Representatives from several organizations were on hand to support the initiative, including the Veteran Mental Health Leadership Coalition, Reason for Hope, Heroic Hearts Project, Veterans Exploring Treatment Solutions and the Foundation for a Healthy Kentucky.

“I am so excited to support Kentucky in this innovative ibogaine research initiative; it’s second to none,” said retired Marine Corps Lt. Gen. Martin Steele, who is CEO of Reason for Hope and president of the Veteran Mental Health Leadership Coalition. “The existing clinical research and the growing body of personal anecdotes suggest that ibogaine when used with careful medical screening, treatment protocols, and oversight, has incredible promise for treating veterans and all others struggling with opioid addiction.”

With great emotion, several people shared their stories of addiction — and recovery after being treated with ibogaine in a country where it is legal.

One was Bobby Laughlin, CEO of New Course Enterprises, a California investment firm, who told how he was able to stay off heroin and other opiates after going through treatment with ibogaine under medical care in 2013.

Laughlin said ibogaine was key to his survival. He said the drug minimized the physiological feeling of opiate withdrawal, removed his compulsion to use opiates, and induced a spiritual experience, which reinstated compassion and love for himself — and was not a habit-forming medicine, and only needed to be used once.

Hubbard said he envisions the project to legalize ibogaine as a public-private partnership. Asked the basis of his $42 million estimate, he said it seemed to be a “reasonable sum” for a “breakthrough opportunity” that, if successful, would not only have a “profound” impact on Kentucky but the rest of the nation.

He said he will discuss the project with the commission at its June 12 meeting and ask it to set a schedule for how to proceed, including one or two public hearings. Then, he said the commission will work toward taking a vote, “perhaps in the fall,” to commit the funds.

“Work would begin to develop the necessary criteria for the announcement of a grant opportunity . . . for any clinical research team that would seek to come in here to develop ibogaine therapy as well as the best practices model for its application to opioid-use disorder,” he said.

The money would come from the $842 million the state is getting from settlements with drug manufacturers and distributors, half of which has been allocated to the state and the other half to cities and counties.

Hubbard said, “I want to emphasize that this is preliminary and we are going to explore that possibility. Given the expense — and it is a significant expense of developing any therapeutic to go through the FDA process — we want to make sure that the money we put up to be matched by clinical research teams will be an adequate sum to get us across the finish line.”

Current treatments have ‘modest’ success

There is no question that Kentucky, and the nation, need to find more effective ways to treat opioid addiction.

“Existing addiction treatment models have modest success rates,” the news release noted. “Some existing treatments are also subject to misuse. Prevailing opioid-use-disorder treatment models carry an average cost of $139,200 per person per recovery attempt.” The release said that from 2017 to May 26, drug companies billed Kentucky Medicaid $1.02 billion for almost 102 million doses of suboxone, “one of the most common and presently effective medications for treating opioid-use disorder.”

Cameron said that while overdose deaths dropped 5% in Kentucky in 2022, the bad news is that 2,127 Kentuckians overdosed last year and the number of overdose deaths in the state has risen 60% since 2019 – with 7,665 Kentuckians dying from overdoses in that time, and about 90% of them caused by opioids.

“We’ve got more work to do … and something has to change,” Cameron said. “Obviously, we need to continue to fund the work that has been ongoing in Kentucky. We also need to explore a new approach. We have to imagine new possibilities. We have to invest in programs and potential solutions for tomorrow.”

Among those attending the event was Ben Chandler, president and CEO of the Foundation for a Healthy Kentucky and a former Democratic attorney general and congressman. He applauded the effort, saying the foundation is hopeful for the health benefits this new initiative could bring to Kentucky.

“We support innovative and data-driven methods to solve health problems,” Chandler said in a news release. “This move to explore new treatments to reverse the chemical effects of opioid addiction, including opioid withdrawal, could be the key to unlocking successful recovery and better long-term health for many Kentuckians.”

Hubbard responds to Beshear

Beshear, asked about the endeavor at his weekly news conference, held shortly after the announcement, said he had only learned about the commission’s “psychedelic research” idea that day.

He said members of the commission from his administration, Health Secretary Eric Friedlander and Van Ingram, executive director of the state Office of Drug Control Policy, said they had not heard about the project.

“They’re supposed to be the ones that decide what projects to fund,” Beshear said of the commission. He also noted that $42 million is more than twice as much as the commission has appropriated in its first round of grants. “This is a huge amount of money,” he said.

Hubbard said in an interview Thursday, that the commission will allocate a total of $30 million by the end of this year. He stressed that it was his idea to explore the use of ibogaine for opioid-use disorder and said he had not formally discussed the initiative with any of the commission members.

“I will take responsibility as chairman for the commission for having conducted individual research in my capacity as chairman for anything and everything that we could possibly discover that could potentially be a breakthrough therapeutic for treatment of opioid disorder,” he said. ” I undertook that effort because the results we are getting with our existing infrastructure are unacceptably mediocre.”

He added, “The entire point of the announcement yesterday was to present the concept to the commission members, as well as to the state as a whole. Every commission member was invited. … And we did not disclose details in advance because this was sensitive information that was developmental. And insofar as we presented it, we wanted to present it on a wide scale, simply because it’s innovative, it’s new, and we think that it should receive spotlight, celebratory attention.”

Friedlander and Ingram did not attend.

Hubbard said he would be “ultra, ultra hesitant” to have any advanced consultations with Beshear’s appointees because he thinks Beshear misrepresented the commission’s work back in January. Beshear said the commission did not have enough guidance or scoring criteria for the grant applications, despite regulations that outlined factors for consideration.

Hubbard said, “I would not be able to have any confidence in the degree to which he, in a context of a press conference, would address it honestly and with good faith.”

Cameron spokeswoman Shellie May, who was on the call with Hubbard, emphasized that no money has been allocated or decided for the project because that is the responsibility of the commission, which includes two Beshear subordinates.

To Beshear’s comment about “a huge amount of money,” Hubbard noted that $42 million would be 10% of the state’s portion of the expected settlement funds and 5% of the whole amount.

“And if we are successful, then we will have developed a therapeutic which will revolutionize how we treat opioid-use disorder – and reduce over the long term the unbelievable consumption of resources being devoted to the treatment of the acute phase of opioid-use disorder, which is the withdrawal symptoms,” he said. “Those are the straight, cold hard facts. When he gets out and he talks about how this is a tremendous amount of money or somehow depriving other potential projects and resources, he’s not even bothered to do the basic math.”

This article is republished from Kentucky Health News, an independent news service of the Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues, based in the School of Journalism and Media at the University of Kentucky, with support from the Foundation for a Healthy Kentucky.

Melissa Patrick is a reporter for Kentucky Health News, an independent news service of the Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues, based in the School of Journalism and Media at the University of Kentucky, with support from the Foundation for a Healthy Kentucky. She has received several competitive fellowships, including the 2016-17 Nursing and Health Care Workforce Media Fellow of the Center for Health, Media & Policy, which allowed her to focus on and write about nursing workforce issues in Kentucky; and the year-long Association of Health Care Journalists 2017-18 Regional Health Journalism Program fellowship. She is a former registered nurse and holds degrees in journalism and community leadership and development from UK.