Each spring, millions of monarch butterflies leave their overwintering sites in the Sierra Madre mountains of central Mexico and begin their annual migration north across the United States.

The exodus and return of the iconic orange and black butterfly is one of the grandest spectacles of the natural world. But that sight is becoming increasingly rare as the monarch’s population has shrunk by nearly 90% in the past two decades, according to federal scientists.

The monarch faces many threats, including the loss of milkweed and other flowering plants across its range, degradation and loss of overwintering groves in both coastal California and Mexico, and the widespread use of herbicides and pesticides. Many of these stressors are worsened by climate change, according to advocates.

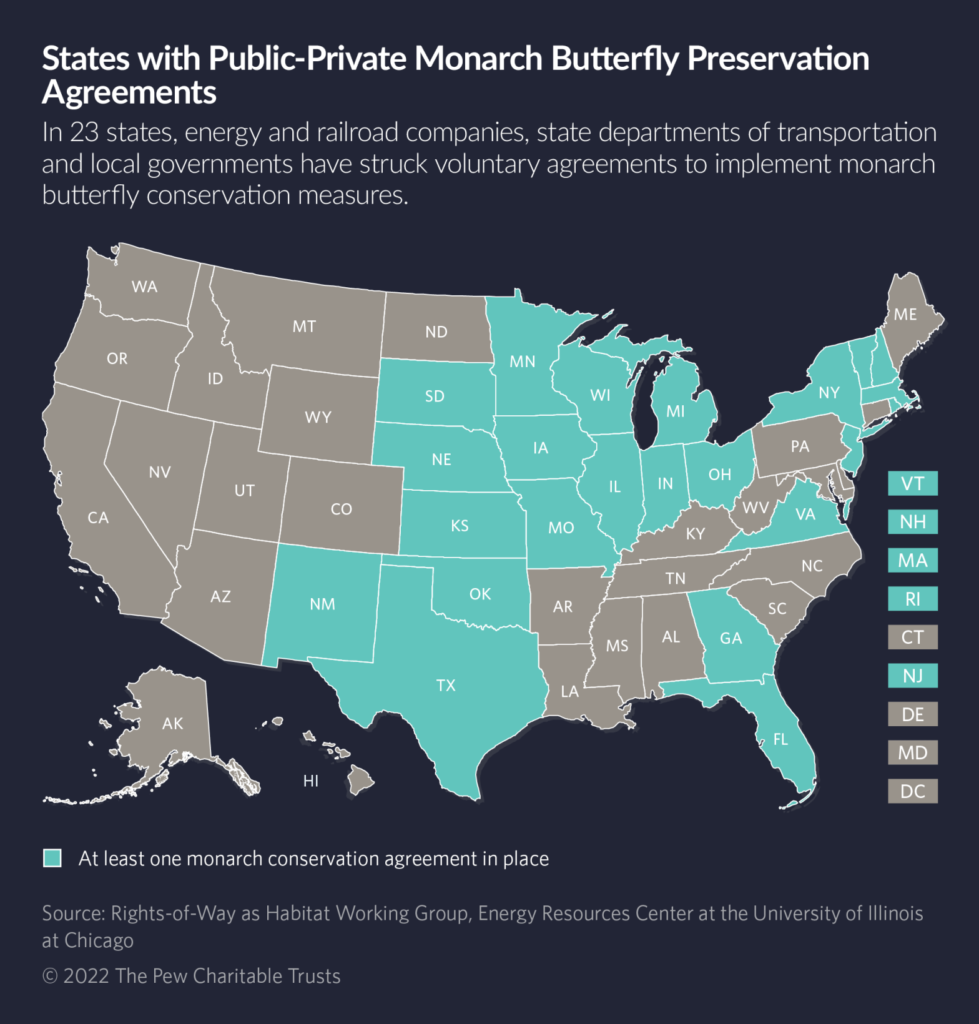

In the past two years, some state transportation departments, local governments, and energy companies across 23 states have committed to preserving monarch habitat in hopes of protecting the species and preventing it from being added to the federal endangered species list.

Nearly three dozen organizations have agreed to preserve some 815,000 acres of monarch habitat along energy and highway corridors since the initiative launched.

The unusual conservation effort sprang from a 2020 agreement between the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Energy Resources Center at the University of Illinois, Chicago, which led a group of experts in developing a butterfly protection plan.

Under the so-called Monarch Candidate Conservation Agreement with Assurances, or CCAA, public and private landowners voluntarily commit to certain conservation actions, including pest and vegetation management to protect the monarch and its habitat. The agreement also requires companies to reduce or remove threats related to the butterflies’ survival. In return, the feds guarantee the landowners will not be required to implement additional conservation measures even if the species is listed.

“The effort is unprecedented in terms of its cross-sector participation and geographic extent,” said Iris Caldwell, program manager of sustainable landscapes for the Energy Resources Center. “This is not only the first CCAA for the monarch butterfly. This is the first nationwide CCAA for any species.”

The group’s goal is to conserve 2.3 million acres across the continental United States.

“The monarch is such an iconic species that it provides us a rallying point that brings people together. That’s important as we’re looking at wide-scale conservation of pollinators,” Caldwell said. “If we can create and conserve monarch habitats it will benefit so many other species.”

But some conservationists are wary of the agreement. Jeffrey Glassberg, president and founder of the North American Butterfly Association, an advocacy group, said while conservation agreements can be effective tools for advancing environmental goals, the most important way to save these butterflies is through large-scale and intensive efforts to re-create prairies in the northern plains that will support their populations.

“The main factors affecting Monarch populations appear to be the degradation of the overwintering sites in Mexico, climate change, and the continued and increasing use of neonicotinoids [insecticides],” Glassberg wrote in an email. “This project will not help with any of those problems.”

The eastern monarch population, which overwinters in Mexico and travels east of the Rocky Mountains, dropped about 88% from 1996 to 2020, from an estimated 383 million to just under 45 million, according to the Fish and Wildlife Service. The western population, which overwinters in California, has dropped more than 99% since the 1980s, from 4.5 million to fewer than 2,000 monarchs, the agency said.

In 2014, conservationists petitioned the Fish and Wildlife Service to place the butterfly on the endangered species list. In December 2020, the agency ruled that monarchs deserve federal protections but that it first must prioritize other species pending for the list.

This article was produced by Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts.

Kristian Hernández writes about social services and housing for Stateline and reports from Texas. Before joining Stateline, he was an investigative reporter for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram and the Center for Public Integrity. Previously, he was an immigration reporter for The Monitor newspaper in South Texas and a courts reporter for Homicide Watch in Washington, D.C. Hernandez is a first-generation Mexican-American with a bachelor’s degree in multimedia journalism from the University of Texas at El Paso and a masters in investigative journalism from American University.