Made of iron, this item has seen better days.

It measures roughly 7 inches by 6 inches and is about 1 inch thick. Weighing 4 pounds, it is heavier than it appears. It is crusted in rust and has a shattered piece of very old glass fused to one side.

The damage almost hides its original design, but you can still make out the shape of a smaller rectangle inset connected to an outer rectangle. The pin on the bottom likely attached this piece to a larger apparatus.

This gnarled and charred piece of cast iron was part of the decorative fence that surrounded Christian County’s third courthouse, which stood from 1838 to 1864. It was unearthed in 2014, when the current courthouse — built in 1869 on the site of its predecessor — got the addition of a much-needed elevator. While digging the shaft within the confines of the existing structure, this piece of ironwork, along with remnants of brick, interior plaster, and foundation stones, were discovered and saved.

This ironwork is on display at the Pennyroyal Area Museum, but what stories does it tell?

First, it tells the story of a town establishing itself as a place of prestige and big ideas. Construction of this two-story brick building began in 1837. At the time, Christian County was barely 40 years old. Our first two courthouses were small, log structures. This building made a bold statement that was meant to assert Christian County’s importance. In 1830, the county’s population was less than 13,000. By 1860, the population had swelled to more than 21,600. Christian County was on an upward swing and had the official buildings to prove it.

Remants of conflict

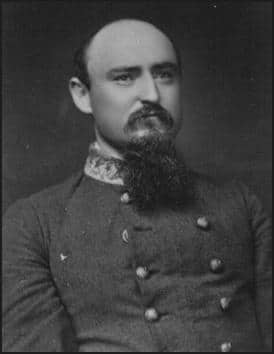

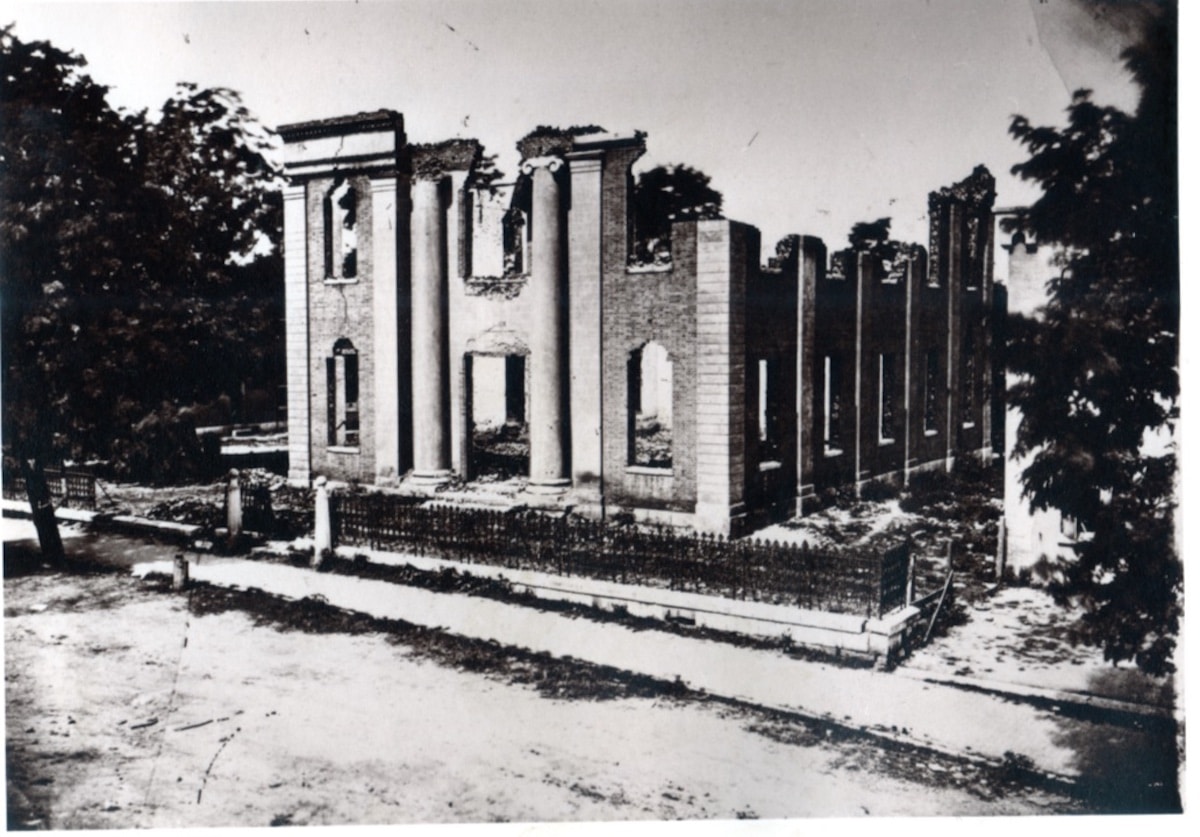

But this ironwork also tells a story of conflict and destruction. On Dec. 12, 1864, Confederate troops under the command of Gen. Hylan B. Lyon burned the building to the ground. Lyon ran a campaign into Western Kentucky to enforce Confederate draft laws and to lure Union troops away from Nashville. Along the way, he burned seven courthouses — including the stately structure on our Main Street.

According to William T. Turner and Chris Gilkey’s book “Firefighting in Hopkinsville,” the fire did not spread thanks to the quick efforts of a bucket brigade. A shell of the building remained. It was photographed by E. L. Foulks in 1865.

Lyon likely targeted the Christian County courthouse because it was being used to quarter federal troops when he made his raid. After being batted back and forth between the warring factions, Hopkinsville was firmly held by Union troops in 1864. Maybe that was enough reason to burn the building. Maybe Lyon was attempting to rival Sherman’s March to the Sea. Maybe Lyon just had a penchant for fire. But I’ve heard an additional theory.

I have heard anecdotal mentions of our courthouse being used as a site to recruit enslaved men into the U.S. military.

Could this have motivated Lyon to torch the building?

The U.S. government authorized the recruitment of African American troops by December 1862 but exempted Kentucky for fear of an adverse reaction from slave owners. The 1st Kansas Colored Infantry Regiment holds the honor of being the first Black unit organized during the Civil War. That was in January 1863.

By mid-1863, the federal government began actively recruiting African American men, but not in Kentucky. Thousands of men rushed over state lines to sign up to fight — to sign up for freedom. In our area, many went south, surprisingly, to join U.S. troops in Union-occupied areas of Tennessee. Fort Defiance in Clarksville, as well as camps at Fort Donelson, Gallatin and Nashville, became recruiting centers for the U.S. Colored Troops by late 1863.

In the summer of 1864, the federal government began actively recruiting African American men in Kentucky. These men joined in droves and quickly filled the U.S. draft quota for many counties. White men could also enlist enslaved men in their place. Camp Nelson near Lexington enlisted 2,000 Black men in two weeks. A recruiting office at Bowling Green enlisted 300 more from surrounding counties in one month.

“When recruiting slowed in September 1864, the army opened additional recruiting offices in Cave City, Franklin, Allensville and Hopkinsville, absorbing numbers of recruits from the large slaveholding counties of western Kentucky,” Dr. Marion B. Lucas wrote in “A History of Blacks in Kentucky From Slavery to Segregation, 1760-1891.” Published by the Kentucky Historical Society in 1992, this book provided me with a nugget of proof that African American men were able to join U.S. forces in Hopkinsville to fight in the Civil War.

The only other documented reference that I have found to a recruiting office here is in a letter published in Charles Meacham’s “History of Christian County Kentucky: from Oxcart to Airplane,” published in 1930. In his chapter “The Confederate Volunteers,” he includes a wartime letter from a Christian County farmer to an expatriate living in Canada.

- RELATED: Meacham’s History of Christian County illustrates value of minutiae

- RELATED: Longtime Hopkinsville newspaper editor wrote history of Christian County

Dated Oct. 28, 1864, the letter details “a negro raid” from Clarksville that recruited about 75 men, leaving many farms without adequate laborers. He also shares that the draft is over for the county and that African American men filled the ranks enough to exempt “all the white men and 300 over.” Before he closes, he states, “We have a negro recruiting office in Hopkinsville.” No additional details are included.

So — there you have it. In late 1864, there was a recruiting office for African American men to join the U.S. Colored Troops in Hopkinsville. Somewhere. Was it in the courthouse burned by Gen. Hylan B. Lyon, leaving us with this scorched piece of cast iron fencing? Honestly, I still don’t know.

But that doesn’t lessen the importance of this artifact and of the stories that it tells. We may never know the exact location where formerly enslaved men joined the ranks of the U.S. military in our community. What we do know is that they joined. They joined at Clarksville, Nashville, Gallatin, Paducah, Bowling Green and Camp Nelson. And I’ve found at least one — John Shade — who listed his enlistment location as Hopkinsville. It’s a start.

Colored Troops from Christian County

According to the Notable Kentucky African Americans Database, approximately 500 veterans of the U.S. Colored Troops listed Christian County, Kentucky, as their birthplace in the 1870 Census. Thanks to the diligent cemetery documentation work of Joe Craver, veteran and former Hopkinsville resident, we have the beginnings of a list of these men.

I have added the names of the men who joined the U.S. Navy that Jennifer P. Brown introduced to us earlier this month, as well as a few that I have found through my own research. They served in the infantry, light artillery, heavy artillery, cavalry and the navy. At least one rose to the rank of corporal; two more achieved the rank of sergeant.

The list includes the names of 52 men. Hopefully, one day we will be able to name them all.

- Nelson Alexander

- James Allensworth

- Nathan Bailey

- Peter Beseley

- Anderson Bradshaw

- Samuel Bradshaw

- James Burke

- Washington Campbell

- John Clardy

- Anderson Cornell

- Holland Elliott

- Jesse Ellis

- Marshal Finch

- Marshall Gholson

- James Giles

- James Henry Gish

- Bat Green

- Lemuel Green

- Charles Hardin

- Jarrott R. Hawkins

- Samuel Hubbard

- John W. Jackson

- William W. Jackson

- Henry Johnson

- John A. Jones

- John “Jack” Kendrick

- Charles Killebrew

- George W. Lander

- Gringo Livell

- George Long

- John Marshall

- Anthony McClellan

- Peyton McCombs

- Samuel McGregor

- Andrew Minter

- Andrew Moore

- Alex Thornton Morehead

- Charlie Parrish

- Peter Postell Sr.

- Edd Robinson

- John Shade

- Henry Sims

- Jordon Stoner

- Minor Thomas

- James Tyler

- Alexander Wagoner

- Willis Ware

- Rev. Stephen Watt

- Monroe Watt

- Wyatt Watt

- Jackson Wiley

- Major Wilson

If any Hoptown Chronicle readers have more information about a man on this list or has insight into others who may have served in the U.S. Colored Troops, please let us know.

Alissa Keller is the executive director of the Museums of Historic Hopkinsville-Christian County. She’s a graduate of Centre College with degrees in history and English and of Clemson University/College of Charleston with a master’s degree in historic preservation. She serves on the Kentucky Historical Society and the Kentucky Museum and Heritage Alliance boards.