On June 5, 1913, Hopkinsville High School celebrated its commencement. Twenty-four seniors strode across the stage of the Union Tabernacle to claim their diplomas. One of them was Margaret Dalton.

While nearly everything about Hopkinsville and the world has altered dramatically since 1913, graduation and the formalities and informalities surrounding it have remained strangely recognizable. Just like today, a litany of preparations took place before a graduate could stride across the stage and claim her diploma.

Getting the Right Dress

Crucial among these, particularly for girls, was finding the right dress. There were no caps and gowns, at least not for HHS in 1913. Female graduates wore white dresses. Getting a dress was not a matter of just going to the store and trying on gowns until one was found that suited. In the words of Sarah Dalton Todd, “… ready-mades were frowned upon.”

Middle- and upper-class women in Hopkinsville around the turn of the century had their dresses made specifically for them. Sarah Dalton Todd lamented that, for her, this usually amounted to one dress a year, made by her mother, Carrie.

She was jealous of Elizabeth Stites, her friend across the street, whose mother hired Rosa Merriweather to make multiple dresses every year for Elizabeth and herself. Sarah recounted visiting Rosa’s house with Elizabeth for fittings. The house was on Coleman Street and was sparklingly clean and had red geraniums. One year, Rosa made Elizabeth and Sarah matching straw bonnets trimmed in gingham.

Both Carrie Dalton and Nora Dalton Davis’ dressmaker of choice was Lou Richardson of Richardson & Co. With graduation approaching, Carrie turned to Richardson & Co. to make Margaret’s graduation dress. Sarah Dalton Todd described the result as “perfect … white lace over satin trimmed in tiny yellow silk flowers.”

Dressmakers

Dressmakers are an interesting historical study because this was one of few occupations that transcended class and race. Careers in which women could run their own businesses were extremely limited. Laundresses, milliners, and dressmakers are the three primary examples for a city of Hopkinsville’s size, and these varied widely in perceived respectability.

In 1913, society still preferred that a woman have no occupation at all. But, if she must work, dressmaking was seen as a respectable engagement. I suspect this perceived respectability came from the working conditions of most dressmakers, who worked out of their own homes, managed no employees, and catered almost exclusively to middle-and-upper-class women and girls.

Rosa Merriweather

This was the case with Rosa Merriweather, the Stites’ dressmaker. She made dresses as a side business to her primary career as a teacher. Rosa’s name might ring a bell on account of her locally well-known husband, polymath Claybron Merriweather.

Rosa was a talented person in her own right. Born in Hopkinsville in 1871 as Rosa F. Morgan, she graduated from Roger Williams University in Nashville. This was a Baptist college that opened in 1866 to educate freedmen. During the 1880s and 1890s, the college enrolled about 250. All were Black, and one-third were women.

By 1900, Rosa lived on Souht Coleman St.ree with her mother, Kitty, and worked as a teacher at Hopkinsville Colored School. In 1907, she married Claybron Merriweather. He published his first book the same year. Rosa was a lifelong educator, and that seems to have been her passion. Every city directory and census record from 1900 onward lists her in a teaching position. Dressmaking was clearly a side gig for her to earn some extra money.

Richardson & Co.

On the opposite end of the spectrum was Richardson & Co., a full-time, fully staffed dressmaking business. Founded by Louise “Lou” Richardson, the business employed as many as 25 seamstresses at its heigh. Twenty-five! This makes Lou Richardson a major employer in circa 1910 Hopkinsville.

Like Rosa Merriweather, Lou Richardson was a Hopkinsville native. Her beginnings were humble. She started working as a seamstress in 1873, a single woman about 19 years old in her parents’ working-class household on Bridge Street. By 1884, her dressmaking business had gained momentum, and she set up shop on the second floor of the Hopper Building, on Main Street. She married Presley Richardson, a Mississippi transplant, the same year.

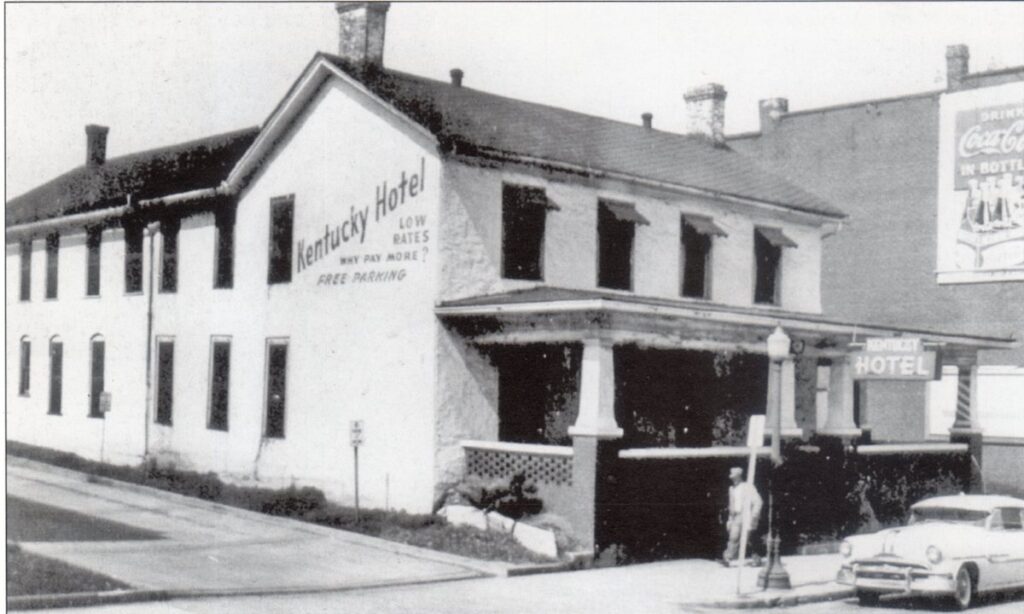

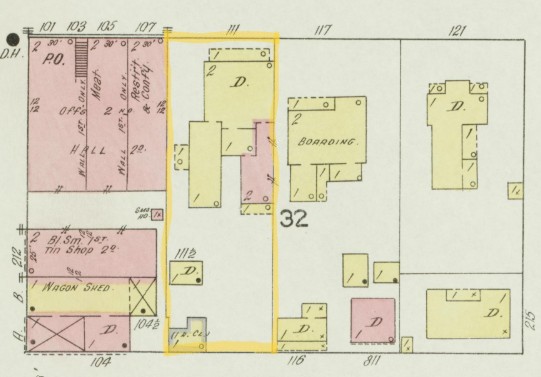

Presley Richardson was a printer, and Lou’s earnings were likely a welcome addition to the household income. By 1900, they had moved to 111 E. Ninth St., which used to stand between where the museum and the Moayon building are today. The dressmaking company operated out of the house, which they enlarged to accommodate the business. Looking at the 1913 Sanborn map, I think Richardson & Co. must have been located in one of the two back wings.

In regards to the company’s operations, tantalizing scraps of information hint at the distribution of jobs and the layout of the workspace. At least two rooms were dedicated to the operation, including one space referred to as the “home room,” which was likely the waiting room and fitting area, and another more self-explanatory “sewing room.”

Lou Richardson was the brains behind the operation, and I think it’s likely she made the major decisions about designs and fabric choice. Around 1908, her brother, Walter Trainum, joined the business as manager. He conducted fittings and probably shopped for fabrics too, sometimes traveling to New York City. Whatever the distribution of responsibilities between Lou and Walter, the nitty gritty work of fabrication was done by the seamstresses. Some of these women boarded with the Richardsons in the 1910 census; Lou’s sister, Donia, and Sarah Moore, a 22-year-old married white woman.

The mysterious Walter Trainum

Walter Trainum was a favorite of young Sarah Dalton Todd’s. She included several snippets about him in her memoir, including a physical description, “a tall handsome young man with white hair.” Particularly fond were her memories of him giving her expensive scraps of fabric from Richardson & Co. to make into dresses for her paper dolls. All Sarah’s friends were jealous of how well-dressed her paper dolls were.

After reading this story several times, I began to wonder why Sarah got such special treatment. Surely other little girls went with their mothers for their dress fittings? It seemed to hint at a closer relationship than just a client’s child. Like many single men in Hopkinsville at that time, Walter Trainum was a boarder. He changed residences frequently, with a different address listed in every city directory. The 1912 Hopkinsville City Directory lists him as boarding a 625 E. Seventh St.

This address didn’t exist. The house numbers progressed 607, 615, 705. I can’t offer hard proof, but I think 625 is a typo. It should be 615, and this would place Walter Trainum as a boarder at the Dalton House in 1912. (Hopkinsville’s big address overhaul in the early 1920s changed our address from 615 to its current 713.)

This would explain why Sarah Dalton Todd had so many memories of Walter and why she got special fabric scraps, as well as why Margaret Dalton and Walter Trainum attended an Athenaeum dinner at the Hotel Latham together in 1914. He was a boarder and a friend of the family.

A dozen American Beauties

At her graduation ceremony, Margaret Dalton received a dozen long-stemmed American Beauty roses, which made a big impression on her younger sister. This might seem like a nice gesture to us, but maybe not that big of a deal. It was a big deal! The cultural impact takes some explaining. In 1913, there were roses…and then there were American Beauty roses.

I love roses, and I must admit that a big part of their appeal is their history. Every old rose has an origin story. What could be better than a flower that comes with its own family history?

This is the American Beauty’s story. The American Beauty cultivar was the best-selling rose in America from its introduction to florists in 1888 into the 1920s. It likely originated in France under the name Madame Ferdinand Jamin. Someone brought the rose to America in 1875 and rebranded it, calling it American Beauty. This rebranding was an astute move and accounts for the rose’s explosive popularity in America, which was the only area of the world where it achieved lasting popularity.

The American Beauty rose was an incredibly expensive flower, nicknamed the “million dollar rose.” The Hopkinsville Kentuckian newspaper reported in 1910 that a dozen American Beauty roses could cost from $6 to $18. Adjusted for inflation, that’s roughly $210 to $630 in today’s money!

From reading local newspapers, it seems to have been a widespread tradition at that time that boys would give girls they were interested in American Beauty roses at graduation. Bowling Green High School even made a rule in 1915 limiting boys to just one American Beauty rose per girl! Any other rose they could give them wheelbarrows full of. But not American Beauty roses. I would love to know who gave Margaret Dalton such an extravagant gift.

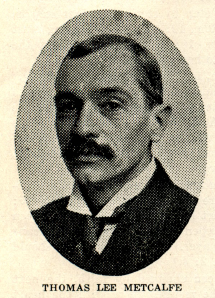

Needless to say, graduation time meant big money for local florists. The primary florist in Hopkinsville in 1913 was Thomas L. Metcalfe. He ran a number of businesses under one roof at the time — dry cleaning, laundering, dying, as well as flowers. By 1915, he had decided to shutter everything except flowers. He became the primary florist in Hopkinsville and opened branches of the business in Clarksville and Madisonville as well.

Coming home again

All this goes to explain why, while writing this article at my parents’ house in South Carolina, I decided on a whim to call the exceptional rose nursery that just happens to be near my parents’ and ask if they had any American Beauty roses in stock. I just happened to get the last plant, which will make its way into the ground at the Dalton house upon my return.

Grace Abernethy is a historic preservationist and artist who specializes in caring for and recreating historic architectural finishes. She earned her Master of Science in Historic Preservation from Clemson University in 2011 and has worked on historic buildings throughout the eastern United States. Abernethy was a recipient of the South Carolina Palmetto Trust for Historic Preservation Award in 2014 and won 2nd place in the Charles E. Peterson Prize for the Historic American Buildings Survey in 2011. She and her husband, Brendan, moved to Hopkinsville from Nashville in 2020. She works as an independent contractor and is a board member of the Hopkinsville History Foundation.